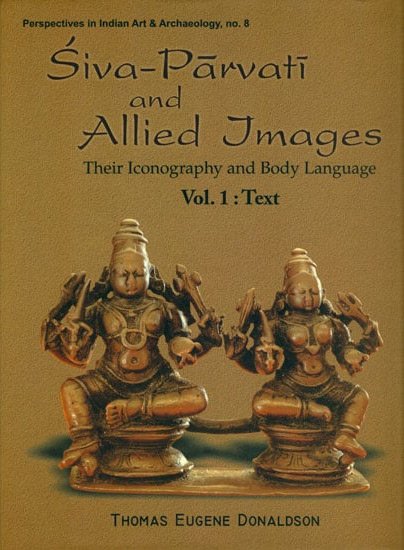

Shiva-Parvati (Iconography)

author: Thomas Eugene Donaldson

edition: 2007, D. K. Printworld Pvt. Ltd.

pages: 1201

ISBN-10: 8124603596

ISBN-13: 9788124603598

Topic: Shilpashastra

Introduction

Images depicting Shiva with Parvati appear as early as the beginning of the Christian era, as noted by N. P. Joshi, whereas no other male "in early Indian iconography has ever been shown along with his consort." Even in his unmanifest form, i.e., as the linga, she is present as "the circular seat of the linga symbolizes Uma." This constant association with his wife continues throughout the ensuring history of Brahmanical art and she appears with him in most of his various manifestations, including many of his violent samhara iconographic forms. In the Agamas when the Devi accompanies Siva, she is standing and is two-armed, displaying kataka with her right hand or holding an utpala while her left arm hangs by her side. When Shiva is seated, as in the Somaskanda-murti, she is also seated and in some cases her left hand is placed on the seat. In the Alingana-Candrasekhara-murti, he is attempting to appease her anger. In the case of the Gajasamhara-murti, she is to be represented shivering and exhibiting her fear and at the same time carrying the infant Skanda in her arm. In the Rauravagama it is stated that she should be portrayed standing by the side of Nrtta-murti Shiva, also cradling a child in her arm.

The body language of Parvati is of particular interest as her interaction with Siva runs the gamut of emotional situations, as indicated in this verse by Vinayadeva:

With embarrassment, for her is naked;

Naively smiling when they say that he hates love;

With wonder at his extra eye and horror of his skulls;

Fearfully before the circle of his snakes

And jealousy because the lady Ganges lies within his crest;

Whom Parvati thus views in many ways,

May he be your protection.

Of primary concern in this study is the physical and emotional interaction between Shiva and Parvati as represented in sculpture throughout the Indian subcontinent. Although this research is centered on the various textual classifications of Hara-Parvati images gleaned from Saiva Agamas by T.A. Gopinatha Rao in his monumental Elements of Hindu Iconography, i.e., Umasahita, Alingana-Candrasekhara, Somaskanda, and Umamaheshvara-murti, other motifs which include both figures are additionally studied, particularly motifs important in establishing or clarifying individual character and emotive peculiarities of the celestial couple. Included among various recent broad studies based on actual images that have increased our knowledge of the various iconographic peculiarities and subgroups are those by N. P. Joshi for images in north India and M.C. Adiceam for images in south India. Other important iconographic studies based on images pertinent to this study, though more limited in respect to area or topic, include books or articles by C. Collins, K. Deva, E. Haque, N.P. Joshi, R. Kalidos, S. Kramrisch, M. Lockwood, P. Pal, M. Rahman, R. Sen Gupta, M.M. Mukhopadhyaya, B. N. Sharma, S. Singh, C. Shivaramamurti, K. M. Suresh, Ramesh D. Trivedi, and Rakesh D. Trivedi. The intent of this study is to incorporate and expand such material, along with my own research, so as to present it and a wealth of visible documentation in a single publication available to a wider audience, including laymen and the general public as well as scholars, students, dealers, collectors and connoisseurs of art.

Part I is devoted to a thumbnail sketch of the mythological background of the major motifs discussed in Part II, the latter following the order sequence of Part I except for Chapter 5, which is divided into two chapters. Chapter 1 is devoted to motifs that accentuate the individual character of Siva and particularly of Parvati that are especially pertinent to their relationship as a married couple. Chapter 2 centers on their marriage and conjugal life, including quarrels and gambling. Chapter 3 is focused on several of the Anugraha-murtis, in particular the Ravananugraha-murti which in north India is essentially an aspect of Umamahesvara-murti while in south India the emphasis is placed more on the Herculean task of Ravana in lifting up the mountain. Chapter 4 is devoted to Saiva motifs in which Parvati (Uma) may or may not be present, or is a spectator, a combatant, or a lesser/superior partner or anga (Part). In the Gangadhara-murti, for example, she is seldom present in examples from north India whereas in south India has despondency, provoked by the presence of Ganga in Shiva's hair, is paramount in the motif as Shiva attempts to placate her with his touch. With Chapter 5 we arrive at the primary thesis of the study, the body pose of Shiva and Uma when represented together, their physical and emotional interaction as man and woman.

In Part ii, As indicated, this chapter is divided into two chapters, with Chapter 5 containing more diversity in respect to category, beginning with the less intimate seated or standing Umasahita-murti, proceeding to the standing. Although Chapter 6 is devoted to one form - the seated Umamaheshvara-murti - it is the most complex in respect to physical and emotional interaction and thus most challenging to the sculptor, who must combine physical/emotional intimacy with hieratic deportment.

The division of the Umamaheshvara-murti into seven basic formats along with numerous variants in this study is based primarily on the pose of Uma (Parvati), the active principle in their relationship, and the struggle of the sculptor to combine aesthetic harmony and beauty with the sacred in an ontological symbol, i.e., Umamahesvara. It is continually repeated in iconographic texts that Uma "should have a handsome bust and hip and both figures should be sculpted in beautiful form," that Siva should have a "lustrous body and be as beautiful as Kama," or, in respect to the sculptor, he "may add any amount of decorative motifs to make the image ornamental," or (with the elephant-hide) "the four legs may be positioned on either side in any artistic manner." As we are reminded by S. Kramrisch, "Each age and school of art and each sculptor realized Umamaheshvara in a separate way, channeled by the iconographic guidance of the manuals on image making." The texts, on the other hand, are often later than the sculptural images and there is little doubt that, in many cases they are based on existing sculptures. This would help to explain the frequent variants in each text as to specifics, as in reference to the ayudhas or in which hands they are placed, on which side Uma is to be placed, the height of Uma in relation to Shiva, or the height of Skanda in Somaskanda images. The visual image thus may often have served as the original "text" or paradigm. The texts are often silent in respect to other details, such as the posture of Uma or her leg alignment, the positioning of the hands of Shiva in holding prescribed ayudhas, or decorative details such as yoga-patta, vanamala, or alignment of bana-lingas on the backslab. Although decorative details may reflect regional or period influence, the pose, posture or composition in images is more widespread and may persist for extended time periods. It is thus apparent that visual images, whether in small terracotta plaques or in copybooks, played a major role in the diffusion of such stereotyped schema throughout the Indian subcontinent and adjacent Hinduized areas.

The somewhat arbitrary classification of Umamaheshvara-murti into various formats and variants for this study is approached essentially from the sculptor's viewpoint. Some of his solutions are obvious experiments of short duration while others were readily accepted and long lasting, indicating that visual paradigms must have been available. In some regions the introduction of a new format often supercedes an earlier solution while in other cases both may coexist. In still other cases a specific format is not introduced into a particular region, even though it is popular elsewhere throughout India. As such the study of compositional postures/formats of embracing couples can provide an additional iconographic tool in determining chronology or place of origin of detached and/or scattered images.

In that this study is primarily descriptive, numerous charts are included to both reduce descriptive details and to identify or clarify certain iconographical peculiarities so that one can instantly recognize similarities, differences, period changes or area popularity. In eighth-tenth century images in Orissa, for example, the serpent above Shiva's right shoulder issues from his earring (sarpa-kundala), in Bihar/Bengal it rises up from behind his back or from his trident, while in central India it slithers from his coiffure, apparently attracted by a lotus or the trident held in his uplifted back hand. By the eleventh century, however, it virtually disappears as a decorative device. On early images throughout north India, Siva invariably is depicted urdhvalinga but from the late eighth century onward this feature is generally limited to Orissa, Bihar/Bengal and Kashmir, The yoga-patta worn by Shiva appears primarily Madhya Pradesh, eastern Rajasthan and northern Uttar Pradesh (Kumaon) while the alignment of bana-lingas at the apex of the backslab, usually four or five in number, is mostly limited to western Madhya Pradesh, central Uttar Pradesh, eastern Rajasthan and Haryana. Umamahesvara-murti images with Uma having four arms are confined primarily to the Bilaspur and Tewar areas of Madhya Pradesh and the Markandi area of Maharashtra. Whereas the added uplifted right hand generally holds a cosmetic stick, the flat, semi-crescent shaped object in her added lower left hand has so far escaped identification. In south Indian images of Ardhanarisvara, in contrast, the female side may have only one arm.

In respect to the distribution of the various motifs and formats, the Ravananugraha-murti is especially popular in the sixth to eighth century cave shrines of western Maharashtra, in ninth through twelfth century images in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, but very rare in north-west India and conspicuously absent in Bihar/Bengal and Nepal. In south India it appears as a motif on Pallava and Cola temple but is most popular on twelfth century Hoyasala and Telugue-Cola temples. The seated format of Umasahita-Candrasekhara-murti, though appearing sporadically throughout north India, is particularly associated with south India, both in stone sculpture and in bronzes, in the latter adopted as the format for the Somaskanda-urti. The Alingana-Candrasekhara-murti is especially popular in the sixth through eighth centuries in Gujarat, seventh through eight centuries in Rajasthan, ninth through eleventh centuries in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, and seventh through tenth centuries in north-west India but virtually non-existent in Orissa or Bihar/Bengal. In south India it appears occasionally in seventh through tenth century in Andhra Pradesh and northern Karnataka but is most popular in Tamil Nadu during the Cola period, particularly with bronze images.

In respect to Umamaheshvara-murti, Format (A), with Uma's lower body facing away from Shiva but her head turned back towards him and her right hand on his leg, is most popular in Uttar Pradesh (especially in Kumaon/Almora), Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Orissa but is rare in Bihar/Bengal and Gujarat. In Nepal it remains the most favourite format both in stone and bronze. In south India it appears primarily with seventh-eighth century images at Aihole and in Andhra Pradesh and with a few Nolamba and early Cola images in Tamil Nadu. Variant (a), with Siva rather awkwardly resting his left arm on the right shoulder of Uma, is most popular in Nepal and north-west India while Variant (b), with Uma's right elbow resting on the left shoulder of Shiva, appears primarily in Orissa with scattered images in Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. Neither of these variants appear in south India. Variant (c), with Uma reciprocating Siva's embrace, appears most often in Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh though isolated images appear throughout most of northern India. In south India it appears with Calukya shrines in northern Karnataka and at Alampur and occasionally on Pallava, Nolamba and early Cola temples. Images of Variant (d), with Shiva lifting the chin of Uma or offering her betel with his left hand, in distributed somewhat evenly throughout northern India, as in Orissa, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Andhra Pradesh. In the more popular format where it is Shiva's right hand that offers betel or lifts her chin, the motif is limited almost exclusively to Bihar/Bengal. Although Variant (d) with Shiva lifting the chin of Uma does not appear with Umamahesvara-murti in south India it does appear with the Gangadhara-murti where is attempting to placate the despondent Uma.

Format (B), with Uma's left knee raised and her stretched right leg folded, especially popular in the tenth and eleventh centuries, appears primarily in Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, though a few examples are noticed in Rajasthan, Orissa and Nepal. This format is conspicuously absent in south India. Format (C), with Siva and Uma assuming duplicate poses with one leg folded and the other pendent, in contrast, is most popular in south India, particularly Karnataka, though a few examples have appeared from Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Nepal. A transitional phase from Format A, Variants (c/d) appears on various images, especially bronze images from Bihar and Orissa or stone Vinadhara-murti from Orissa and the Almora region of northern Uttar Pradesh. Images in Format (D), with Shiva and Uma seated in a duplicate pose with both legs crossed, appear sporadically throughout India but are most prevalent in Bihar, north-west India, and especially Nepal. In the latter two areas the format is employed for the Kumbheshvara form of Umamaheshvara-murti.

Format (E), with Shiva and Uma in mirror image lalitasana with their outside leg pendent, is by far the most popular late format for Umamaheshvara-murti, generally superceding the earlier formats. It is particularly prevalent in Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Orissa, but appears throughout India and even on numerous late images in Nepal. The loosely defined Format (F), with both legs of Uma pendent, appears scattered throughout India in variant forms, but is most popular in north-west India, northern Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. In respect to the Vrsavahana-murti, images with the bull in a gallop or trot appear mostly in south India, as on Calukya and Nolamba ceilings or on late gopuram in Tamil Nadu. Images with Nandi standing or walking are most popular in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan in northern India and on Hoyasala temples in Karnataka. Images with Nandi reclining appear most frequently in the Kumaon area of Uttar Pradesh, north-west India, and Rajasthan/Gujarat while rare in south India. Whether galloping, standing, or reclining, the Vrsavahana-murti is conspicuously absent or rare in Orissa or Bihar/Bengal.

In respect to the comparative size of the celestial couple, in north India they generally are represented as in nature with Siva being slightly taller than Uma, though there are obvious exceptions depending on the period, region, and sculptural format. In Orissa this naturalistic convention persists throughout the sixth to fourteenth centuries for all formats, a rare exception being a bronze Umamaheshvara-muirti. In Nepal, in contrast, Uma is generally reduced in size, the top of her head rarely extending above Siva's shoulders except for the standing Umasahita- and Alingana-murtis. In Bihar/Bengal the image of Uma is reduced in size for the saptapadi ritual, where she stands in front of Shiva, and in numerous bronze images of Umamaheshvara-murti. Whereas in Format (B) the comparative size of Uma is most varied, in Format (E) it is most consistent, being naturalistic except in Nepal. Format (D) is similar except in Nepal and northwest India where Uma is reduced in size. In format (F), especially in later examples, the size of Uma is greatly reduced so that she appears childlike. In south India the image of Uma is generally not as tall as in north India, the top of her head (except for her tall mukuta) seldom extending above Shiva's shoulders. Shiva's dominance is further suggested by occasionally having Uma placed slightly behind him so that part of his body overlaps her; or, when the couple is framed by a single aureole, Shiva is centrally placed whereas Uma is shifted to the extreme left side of the composition, placed in front of the side supports of the torana design of the backslab.

Numerous images appear in more than one chart as they combine various motifs or formats, such as Ravananugraha and Umamaheshvara, or Umamaheshvara and Vrsavahana-murti. Although the number of images included may be small in contrast to the total number still existing, the sampling is sufficient to give us a representative picture of the various regional iconographic peculiarities and the distribution, popularity and staying power of the different formats. I have situated the sites according to their present state boundaries for the sake of easy access for the reader. For the most part I have retained the suggestive date and provenance for published or museum sculptures as my study is concerned primarily with iconographic peculiarities, only one of numerous tools for determining provenance or date.