Mahabharata (English)

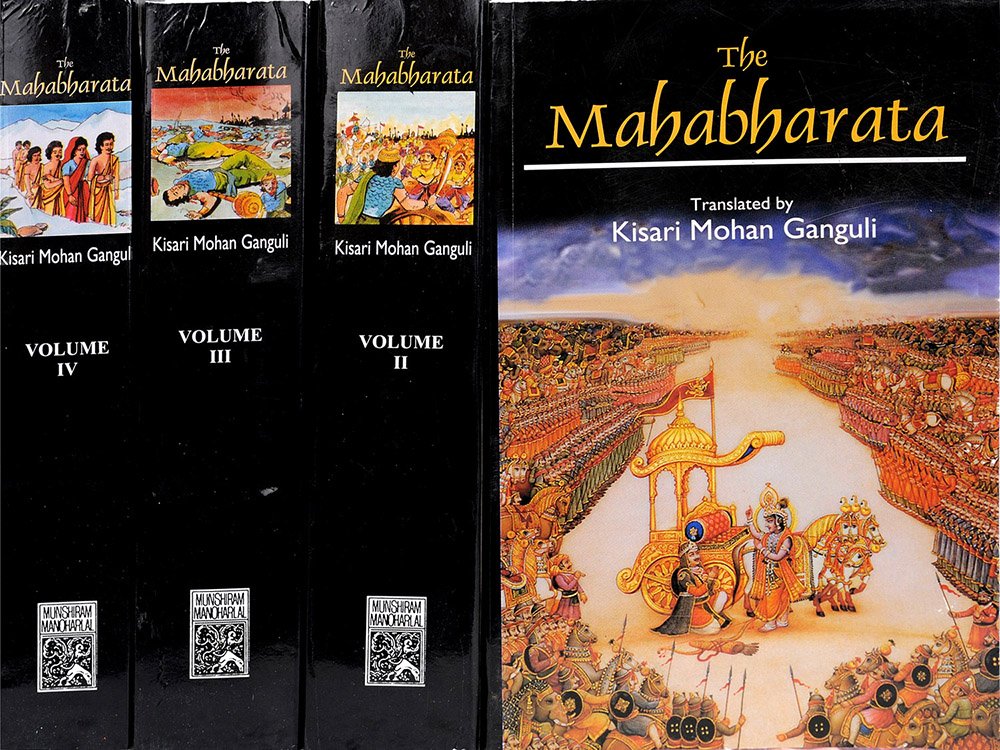

by Kisari Mohan Ganguli | 2,566,952 words | ISBN-10: 8121505933

The English translation of the Mahabharata is a large text describing ancient India. It is authored by Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa and contains the records of ancient humans. Also, it documents the fate of the Kauravas and the Pandavas family. Another part of the large contents, deal with many philosophical dialogues such as the goals of life. Book...

Section II

"Vaisampayana said, 'When that night passed away and day broke in, those Brahmamas who supported themselves by mendicancy, stood before the Pandavas of exalted deeds, who were about to enter the forest.

Then king Yudhishthira, the son of Kunti, addressed them, saying,

"Robbed of our prosperity and kingdom, robbed of everything, we are about to enter the deep woods in sorrow, depending for our food on fruits and roots, and the produce of the chase. The forest too is full of dangers, and abounds with reptiles and beasts of prey. It appears to me that you will certainly have to suffer much privation and misery there. The sufferings of the Brahmanas might overpower even the gods. That they would overwhelm me is too certain. Therefore, O Brahmana, go you back whithersoever you list!'

"The Brahmanas replied,

'O king, our path is even that on which you are for setting out! It behoves you not, therefore, to forsake us who are your devoted admirers practising the true religion! The very gods have compassion upon their worshippers,—specially upon Brahmanas of regulated lives!'

"Yudhishthira said,

'We regenerate ones, I too am devoted to the Brahmanas! But this destitution that has overtaken me overwhelmed me with confusion! These my brothers that are to procure fruits and roots and the deer (of the forest) are stupefied with grief arising from their afflictions and on account of the distress of Draupadi and the loss of our kingdom! Alas, as they are distressed, I cannot employ them in painful tasks!'

"The Brahmanas said,

'Let no anxiety, O king, in respect of our maintenance, find a place in your heart! Ourselves providing our own food, we shall follow you, and by meditation and saying our prayers we shall compass your welfare while by pleasant converse we shall entertain you and be cheered ourselves.'

"Yudhishthira said,

'Without doubt, it must be as you say, for I am ever pleased with the company of the regenerate ones! But my fallen condition makes me behold in myself an object of reproach! How shall I behold you all, that do not deserve to bear trouble, out of love for me painfully subsisting upon food procured by your own toil? Oh, fie upon the wicked sons of Dhritarashtra!'

"Vaisampayana continued. 'Saying this, the weeping king sat himself down upon the ground. Then a learned Brahmana, Saunaka by name versed in self-knowledge and skilled in the Sankhya system of yoga, addressed the king, saying,

'Causes of grief by thousands, and causes of fear by hundreds, day after day, overwhelm the ignorant but not the wise. Surely, sensible men like you never suffer themselves to be deluded by acts that are opposed to true knowledge, fraught with every kind of evil, and destructive of salvation. O king, in you dwells that understanding furnished with the eight attributes which is said to be capable of providing against all evils and which results from a study of the Sruti (Vedas) and scriptures! And men like unto you are never stupefied, on the accession of poverty or an affliction overtaking their friends, through bodily or mental uneasiness! Listen, I shall tell the slokas which were chanted of old by the illustrious Janaka touching the subject of controlling the self! This world is afflicted with both bodily and mental suffering. Listen now to the means of allaying it as I indicate them both briefly and in detail.

Disease, contact with painful things, toil and want of objects desired.—these are the four causes that induce bodily suffering. And as regards disease, it may be allayed by the application of medicine, while mental ailments are cured by seeking to forget them yoga-meditation. For this reason, sensible physicians first seek to allay the mental sufferings of their patients by agreeable converse and the offer of desirable objects And as a hot iron bar thrust into a jar makes the water therein hot, even so does mental grief bring on bodily agony.

And as water quenches fire, so does true knowledge allay mental disquietude. And the mind attaining ease, the body finds ease also. It seems that affection is the root of all mental sorrow. It is affection that makes every creature miserable and brings on every kind of woe. Verily affection is the root of all misery and of all fear, of joy and grief of every kind of pain.

From affection spring all purposes, and it is from affection that spring the love of worldly goods! Both of these (latter) are sources of evil, though the first (our purposes) is worse than the second. And as (a small portion of) fire thrust into the hollow of a tree consumes the tree itself to its roots, even so affection, ever so little, destroyes both virtue and profit. He cannot be regarded to have renounced the world who has merely withdrawn from worldly possessions. He, however, who though in actual contact with the world regards its faults, may be said to have truly renounced the world.

Freed from every evil passion, soul dependent on nothing with such a one has truly renounced the world. Therefore, should no one seek to place his affections on either friends or the wealth he has earned. And so should affection for one’s own person be extinguished by knowledge. Like the lotus-leaf that is never drenched by water, the souls of men capable of distinguishing between the ephemeral and the everlasting, of men devoted to the pursuit of the eternal, conversant with the scriptures and purified by knowledge, can never be moved by affection.

The man that is influenced by affection is tortured by desire; and from the desire that springs up in his heart his thirst for worldly possessions increases. Verily, this thirst is sinful and is regarded as the source of all anxieties. It is this terrible thirst, fraught with sin that leans unto unrighteous acts. Those find happiness that can renounce this thirst, which can never be renounced by the wicked, which decays not with the decay of the body, and which is truly a fatal disease! It has neither beginning nor end. Dwelling within the heart, it destroyes creatures, like a fire of incorporeal origin. And as a faggot of wood is consumed by the fire that is fed by itself, even so does a person of impure soul find destruction from the covetousness born of his heart.

And as creatures endued with life have ever a dread of death, so men of wealth are in constant apprehension of the king and the thief, of water and fire and even of their relatives. And as a morsel of meat, if in air, may be devoured by birds; if on ground by beasts of prey; and if in water by the fishes; even so is the man of wealth exposed to dangers wherever he may be. To many the wealth they own is their bane, and he that beholding happiness in wealth becomes wedded to it, knows not true happiness. And hence accession of wealth is viewed as that which increases covetousness and folly.

Wealth alone is the root of niggardliness and boastfulness, pride and fear and anxiety! These are the miseries of men that the wise see in riches! Men undergo infinite miseries in the acquisition and retention of wealth. Its expenditure also is fraught with grief. Nay, sometimes, life itself is lost for the sake of wealth! The abandonment of wealth produces misery, and even they that are cherished by one’s wealth become enemies for the sake of that wealth! When, therefore, the possession of wealth is fraught with such misery, one should not mind its loss. It is the ignorant alone who are discontented. The wise, however, are always content. The thirst of wealth can never be assuaged.

Contentment is the highest happiness; therefore, it is, that the wise regard contentment as the highest object of pursuit. The wise knowing the instability of youth and beauty, of life and treasure-hoards, of prosperity and the company of the loved ones, never covet them. Therefore, one should refrain from the acquisition of wealth, bearing the pain incident to it. None that is rich free from trouble, and it is for this that the virtuous applaud them that are free from the desire of wealth. And as regards those that pursue wealth for purposes of virtue, it is better for them to refrain altogether from such pursuit, for, surely, it is better not to touch mire at all than to wash it off after having been besmeared with it. And, O Yudhishthira, it behoves you not to covet anything! And if you wouldst have virtue, emancipate thyself from desire of worldly possessions!'

"Yudhishthira said,

'O Brahmana, this my desire of wealth is not for enjoying it when obtained. It is only for the support of the Brahmanas that I desire it and not because I am actuated by avarice! For what purpose, O Brahmana, does one like us lead a domestic life, if he cannot cherish and support those that follow him? All creatures are seen to divide the food (they procure) amongst those that depend on them.[2] So should a person leading a domestic life give a share of his food to Yatis and Brahmacarins that have renounced cooking for themselves.

The houses of the good men can never be in want of grass (for seat), space (for rest), water (to wash and assuage thirst), and fourthly, sweet words. To the weary a bed,—to one fatigued with standing, a seat,—to the thirsty, water,—and to the hungry, food should ever be given. To a guest are due pleasant looks and a cheerful heart and sweet words. The host, rising up, should advance towards the guest, offer him a seat, and duly worship him. Even this is eternal morality. They that perform not the Agnihotra[2] not wait upon bulls, nor cherish their kinsmen and guests and friends and sons and wives and servants, are consumed with sin for such neglect.

None should cook his food for himself alone and none should slay an animal without dedicating it to the gods, the pitris, and guests. Nor should one eat of that food which has not been duly dedicated to the gods and pitris. By scattering food on the earth, morning and evening, for (the behoof of) dogs and Chandalas and birds, should a person perform the Visvedeva sacrifice.[3] He that eats the Vighasa, is regarded as eating ambrosia. What remaines in a sacrifice after dedication to the gods and the pitris is regarded as ambrosia; and what remaines after feeding the guest is called Vighasa and is equivalent to ambrosia itself.

Feeding a guest is equivalent to a sacrifice, and the pleasant looks the host casts upon the guest, the attention he devotes to him, the sweet words in which he addresses him, the respect he pays by following him, and the food and drink with which he treats him, are the five Dakshinas[4] in that sacrifice. He who gives without stint food to a fatigued wayfarer never seen before, obtaines merit that is great, and he who leading a domestic life, follows such practices, acquires religious merit that is said to be very great. O Brahmana, what is your opinion on this?"

"Saunaka said,

'Alas, this world is full of contradictions! That which shames the good, gratifies the wicked! Alas, moved by ignorance and passion and slaves of their own senses, even fools perform many acts of (apparent merit) to gratify in after-life their appetites! With eyes open are these men led astray by their seducing senses, even as a charioteer, who has lost his senses, by restive and wicked steeds! When any of the six senses finds its particular object, the desire springs up in the heart to enjoy that particular object. And thus when one’s heart proceeds to enjoy the objects of any particular sense a wish is entertained which in its turn gives birth to a resolve.

And finally, like unto an insect falling into a flame from love of light, the man falls into the fire of temptation, pierced by the shafts of the object of enjoyment discharged by the desire constituting the seed of the resolve! And thenceforth blinded by sensual pleasure which he seeks without stint, and steeped in dark ignorance and folly which he mistakes for a state of happiness, he knows not himself! And like unto a wheel that is incessantly rolling, every creature, from ignorance and deed and desire, falls into various states in this world, wandering from one birth to another, and ranges the entire circle of existences from a Brahma to the point of a blade of grass, now in water, now on land, and now against in the air!

'This then is the career of those that are without knowledge. Listen now to the course of the wise they that are intent on profitable virtue, and are desirous of emancipation! The Vedas enjoin act but renounce (interest in) action. Therefore, should you act, renouncing Abhimana,[5] performance of sacrifices, study (of the Vedas), gifts, penance, truth (in both speech and act), forgiveness, subduing the senses, and renunciation of desire,—these have been declared to be the eight (cardinal) duties constituting the true path. Of these, the four first pave the way to the world of the pitris. And these should be practised without Abhimana.

The four last are always observed by the pious, to attain the heaven of the gods. And the pure in spirit should ever follow these eight paths. Those who wish to subdue the world for purpose of salvation, should ever act fully renouncing motives, effectually subduing their senses, rigidly observing particular vows, devotedly serving their preceptors, austerely regulating their fare, diligently studying the Vedas, renouncing action as mean and restraining their hearts. By renouncing desire and aversion the gods have attained prosperity. It is by virtue of their wealth of yoga[6] that the Rudras, and the Sadhyas, and the Adityas and the Vasus, and the twin Asvins, rule the creatures.

Therefore, O son of Kunti, like unto them, do you, O Bharata, entirely refraining from action with motive, strive to attain success in yoga and by ascetic austerities. You have already achieved such success so far as your debts to your ancestors, both male and female concerned, and that success also which is derived from action (sacrifices). Do you, for serving the regenerate ones endeavour to attain success in penances. Those that are crowned with ascetic success, can, by virtue of that success, do whatever they list; do you, therefore, practising asceticism realise all your wishes."

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

This seems to be the obvious. There is a different reading however. For Drie--cyate-seen, some texts have Sasyate--applauded. Nilakantha imagines that the meaning is "As distribution (of food) amongst the various classes of beings like the gods, the Pitris, &c., is applauded &c., &c."

[2]:

A form of sacrifice which consists in pouring oblations of clarified butter with prayers into a blazing fire. It is obligatory on Brahmanas and Kshatriyas, except those that accept certain vows of great austerity.

[3]:

The Viswedeva sacrifice is the offer of food to all creatures of the earth (by scattering a portion).

[4]:

A gift. It may be of various kinds. The fees paid to Brahmanas assisting at sacrifices and religious rites, such as offering oblations to the dead, are Dakshinas, as also gifts to Brahmanas on other occasions particularly when they are fed, it bring to this day the custom never to feed a Brahmana without paying him a pecuniary fee. There can be no sacrifice, no religious rite, without Dakshina.

[5]:

Reference to self, i.e. without the motive of bettering one's own self, or without any motive at all. (This contains the germ of the doctrine preached more elaborately in the Bhagavad gita).

[6]:

This Yoga consists, in their case, of a combination of attributes by negation of the contrary ones, i.e. by renunciation of motives in all they do.

Conclusion:

This concludes Section II of Book 3 (Vana Parva) of the Mahabharata, of which an English translation is presented on this page. This book is famous as one of the Itihasa, similair in content to the eighteen Puranas. Book 3 is one of the eighteen books comprising roughly 100,000 Sanskrit metrical verses.

FAQ (frequently asked questions):

Which keywords occur in Section II of Book 3 of the Mahabharata?

The most relevant definitions are: Brahmana, Brahmanas, Yudhishthira, pitris, Vedas, yoga; since these occur the most in Book 3, Section II. There are a total of 32 unique keywords found in this section mentioned 65 times.

What is the name of the Parva containing Section II of Book 3?

Section II is part of the Aranyaka Parva which itself is a sub-section of Book 3 (Vana Parva). The Aranyaka Parva contains a total of 10 sections while Book 3 contains a total of 13 such Parvas.

Can I buy a print edition of Section II as contained in Book 3?

Yes! The print edition of the Mahabharata contains the English translation of Section II of Book 3 and can be bought on the main page. The author is Kisari Mohan Ganguli and the latest edition (including Section II) is from 2012.