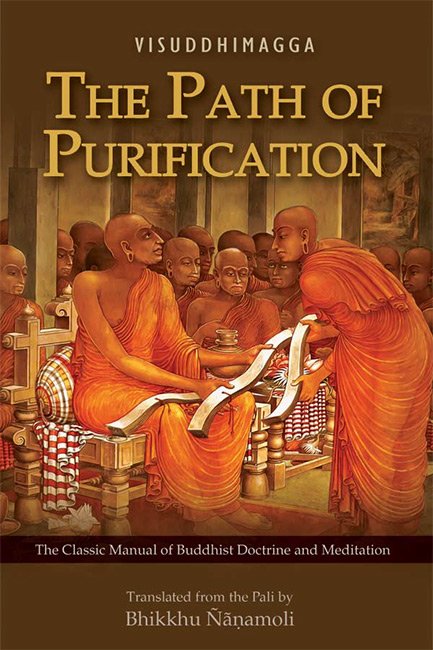

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

The English translation of the Visuddhimagga written by Buddhaghosa in the 5th Century. It contains the essence of the the teachings found in the Pali Tripitaka and represents, as a whole, an exhaustive meditation manual. The work consists of the three parts—1) Virtue (Sila), 2) Concentration (Samadhi) and 3) Understanding (Panna) covering twenty-t...

Concluding Remarks

Current standard English has been aimed at and preference given always to simplicity. This has often necessitated cutting up long involved sentences, omitting connecting particles (such as pana, pan’ettha, yasmā when followed by tasmā, hi, kho, etc.), which serve simply as grammatical grease in long chains of subordinate periods. Conversely the author is sometimes extraordinarily elliptic (as in XIV.46 and XVI.68f.), and then the device of square brackets has been used to add supplementary matter, without which the sentence would be too enigmatically shorthand. Such additions (kept to the minimum) are in almost every case taken from elsewhere in the work itself or from the Paramatthamañjūsā. Round brackets have been reserved for references and for alternative renderings (as, e.g., in I.140) where there is a sense too wide for any appropriate English word to straddle.

A few words have been left untranslated (see individual notes). The choice is necessarily arbitrary. It includes kamma, dhamma (sometimes), jhāna, Buddha (sometimes), bhikkhu, Nibbāna, Pātimokkha, kasiṇa, Piṭaka, and arahant. There seemed no advantage and much disadvantage in using the Sanskrit forms, bhikåu, dharma, dhyāna, arhat, etc., as is sometimes done (even though”karma” and “nirvana” are in the Concise Oxford Dictionary), and no reason against absorbing the Pali words into English as they are by dropping the diacritical marks. Proper names appear in their Pali spelling without italics and with diacritical marks. Wherever Pali words or names appear, the stem form has been used (e.g. Buddha, kamma) rather than the inflected nominative (Buddho, kammaṃ), unless there were reasons against it.[1]

Accepted renderings have not been departed from nor earlier translators gone against capriciously. It seemed advisable to treat certain emotionally charged words such as “real” (especially with a capital R) with caution. Certain other words have been avoided altogether. For example, vassa (“rains”) signifies a three-month period of residence in one place during the rainy season, enjoined upon bhikkhus by the Buddha in order that they should not travel about trampling down crops and so annoy farmers. To translate it by “lent” as is sometimes done lets in a historical background and religious atmosphere of mourning and fasting quite alien to it (with no etymological support). “Metempsychosis” for paṭisandhi is another notable instance.[2]

The handling of three words, dhamma, citta, and rūpa (see Glossary and relevant notes) is admittedly something of a makeshift. The only English word that might with some agility be used consistently for dhamma seems to be “idea”; but it has been crippled by philosophers and would perhaps mislead. Citta might with advantage have been rendered throughout by “cognizance,” in order to preserve its independence, instead of rendering it sometimes by “mind” (shared with mano) and sometimes by “consciousness” (shared with viññāṇa) as has been done. But in many contexts all three Pali words are synonyms for the same general notion (see XIV.82); and technically, the notion of “cognition,” referred to in its bare aspect by viññāṇa, is also referred to along with its concomitant affective colouring, thought and memory, etc., by citta. So the treatment accorded to citta here finds support to that extent. Lastly “mentality-materiality” for nāma-rūpa is inadequate and “nameand-form” in some ways preferable. “Name” (see Ch. XVIII, n.4) still suggests nāma’s function of “naming”; and “form” for the rūpa of the rūpakkhandha (“materiality aggregate”) can preserve the link with the rūpa of the rūpāyatana, (“visible-object base”) by rendering them respectively with “material form aggregate” and “visible form base”—a point not without philosophical importance. A compromise has been made at Chapter X.13. “Materiality” or “matter” wherever used should not be taken as implying any hypostasis, any “permanent or semipermanent substance behind appearances” (the objective counterpart of the subjective ego), which would find no support in the Pali.

The editions of Sri Lanka, Burma and Thailand have been consulted as well as the two Latin-script editions; and Sinhalese translations, besides. The paragraph numbers of the Harvard University Press edition will be found at the start of paragraphs and the page numbers of the Pali Text Society’s edition in square brackets in the text (the latter, though sometimes appearing at the end of paragraphs, mark the beginnings of the PTS pages). Errors of readings and punctuation in the PTS edition not in the Harvard edition have not been referred to in the notes.

For the quotations from the Tipiṭaka it was found impossible to make use of existing published translations because they lacked the kind of treatment sought. However, other translation work in hand served as the basis for all the Piṭaka quotations.

Rhymes seemed unsuitable for the verses from the Tipiṭaka and the “Ancients”; but they have been resorted to for the summarizing verses belonging to the Visuddhimagga itself. The English language is too weak in fixed stresses to lend itself to Pali rhythms, though one attempt to reproduce them was made in Chapter IV.

Where a passage from a sutta is commented on, the order of the explanatory comments follows the Pali order of words in the original sentence, which is not always that of the translation of it.

In Indian books the titles and subtitles are placed only at, the end of the subject matter. In the translations they have been inserted at the beginning, and some subtitles added for the sake of clarity. In this connection the title at the end of Chapter XI, “Description of Concentration” is a “heading” applying not only to that chapter but as far back as the beginning of Chapter III. Similarly, the title at the end of Chapter XIII refers back to the beginning of Chapter XII. The heading “Description of the Soil in which Understanding Grows” (paññā-bhūmi-niddesa) refers back from the end of Chapter XVII to the beginning of Chapter XIV.

The book abounds in “shorthand” allusions to the Piṭakas and to other parts of itself. They are often hard to recognize, and failure to do so results in a sentence with a half-meaning. It is hoped that most of them have been hunted down.

Criticism has been strictly confined to the application of Pali Buddhist standards in an attempt to produce a balanced and uncoloured English counterpart of the original. The use of words has been stricter in the translation itself than the Introduction to it.

The translator will, of course, have sometimes slipped or failed to follow his own rules; and there are many passages any rendering of which is bound to evoke query from some quarter where there is interest in the subject. As to the rules, however, and the vocabulary chosen, it has not been intended to lay down laws, and when the methods adopted are described above that is done simply to indicate the line taken: Janapada-niruttiṃ nābhiniveseyya, samaññaṃ nāti-dhāveyyā ti (see XVII.24).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Pronounce letters as follows: a as in countryman, ā father, e whey, i chin, ī machine, u full, ū rule; c church (always), g give (always); h always sounded separately, e.g. bh in cab-horse, ch in catch him (not kitchen), ph in upholstery (not telephone), th in hothouse (not pathos), etc.; j joke; ṃ and ṅ as ng in singer, ñ as ni in onion; ḍ, ḷ, ṇ and ṭ are pronounced with tongue-tip on palate; d, t, n and with tongue-tip on teeth; double consonants as in Italian, e.g. dd as in mad dog (not madder), gg as in big gun (not bigger); rest as in English.

[2]:

Of the principal English value words, “real,” “truth,” “beauty,” “good,” “absolute,” “being,” etc.: “real” has been used for tatha (XVI.24), “truth” allotted to sacca (XVI.25) and “beauty” to subha (IX.119); “good” has been used sometimes for the prefix su- and also for the adj. kalyāṇa and the subst. attha. “Absolute” has not been employed, though it might perhaps be used for the word advaya, which qualifies the word kasiṇa (“universality,” “totalization”) at M II 14, and then: “One (man) perceives earth as a universality above, below, around, absolute, measureless” could be an alternative for the rendering given in V.38. “Being” (as abstract subst.) has sometimes been used for bhava, which is otherwise rendered by “becoming.”