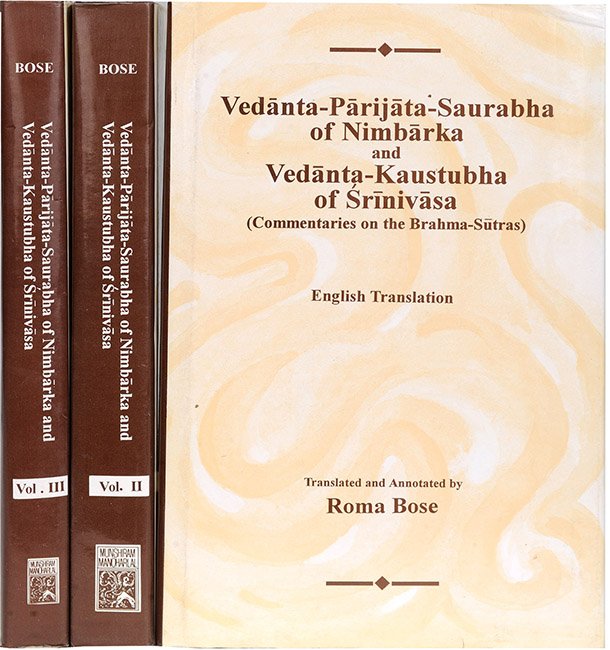

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.2.1, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.2.1

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.2.1 by Roma Bose:

“(That which consists of mind is Brahman), because of the teaching of what is celebrated everywhere.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

Beginning: ‘All this, verily, is Brahman, emanating from him, disappearing into him and breathing in him;—tranquil, let one meditate on him thus’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1[1]), Scripture continues: ‘Consisting of mind, having the vital breath for his body’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.2[2]). Here, the object which is to be meditated on as consisting of mind is to be understood as the Highest self, the cause of all, and not as the individual soul. Why? Because the highest self alone, celebrated in all the Vedāntas, is taught in the above passages, viz. ‘All this, verily, is Brahman’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Thus, in the first section, the concordance of the scriptural texts with regard to the holy Lord Vāsudeva has been shown,—He who is the object of enquiry, the greatest Being, the cause of the origin and the rest of the world, having Scripture for His sole proof, omniscient, without an equal or a superior and the one mass of infinite auspicious qualities. Now, in the following two sections, the reverend teacher of the Veda is showing that those texts,—some of which indistinctly indicate the individual soul and the rest, and some of which distinctly do so,—all refer to Him alone.

The Chandogas record the following: ‘All this, verily, is Brahman, emanating from him, disappearing into him, and breathing in him;—tranquil, let one meditate (on him) thus. Now, a person consists of determination. According to what his determination is in this world, so does he become on departing hence. Let him form a determination. He who consists of mind, has the vital-breath for his body, is of the form of light’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1-2[3]) and so on. Here, a doubt arises, viz. whether the individual soul[4] should be understood as the object to be meditated on, possessed of the attributes of consisting of mind and the rest, or the Highest self. What is reasonable here?

(Prima facie view.)

If it be suggested: The individual soul. Why? Because the individual soul is well-known to have the mind and the vital-breath as its instruments; because Scripture declares that Lord Brahman, the Supreme Being, has no connection with mind and the vital-breath, in the passage: ‘Without the vital-breath, without mind, pure’ (Munch 2.1.2); and, finally, because having the heart for its abode as well as being atomic, stated in the passage: ‘This is the soul[5] within the heart, smaller than a grain of rice, or a barley-corn’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.3), are possible in the case of the limited individual soul alone. If it be objected: of the six proofs, viz. scriptural statement, mark, text, topic, place and name, each succeeding one is weaker than the preceding one. Of these, scriptural statement means an independent statement, and mark means the power of words (to indicate some meaning). Now, here, the scriptural statement, viz.: ‘All this, verily, is Brahman’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1), is of a greater force than the mark of the individual soul, viz. consisting of mind and the rest, it being mentioned first, (the rule being that of these six, each preceding one is of a greater force than each succeeding one). Hence, Brahman alone, mentioned above, is to be construed here as the object to be meditated on,—(we reply:) no, because as that text fulfils its purpose simply by teaching, as a means to the attainment of tranquillity, that everything has Brahman for its soul, thus: ‘Tranquil, let one meditate so it is not concerned with laying down any injunction regarding the meditation on Brahman (here ends the original Prima facie view)...

(Correct conclusion.)

We reply:—The highest soul alone, possessed of the attributes of consisting of mind and the rest, is the object to be meditated on. Why? “Because” the cause of the origin and the rest of the world, “celebrated everywhere”, i.e. in all the Vedāntas, “is taught” as the cause of all, as the soul of all, here in the text: ‘All this, verily, is Brahman’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1). Or, else, “because” the attributes of ‘consisting of mind’ and the rest, “celebrated” in all the Vedāntas as belonging to the Supreme Brahman, thus: ‘Consisting of mind, leader of the vital-breath and the body (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.2.7), ‘This ether that is within the heart,—therein is the person, consisting of mind (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 1.6), and so on, “are taught”. Of these, ‘consisting of mind’ means ‘capable of being apprehended by a purified mind’; ‘having the vital-breath for the body’ means ‘being the support and the ruler of even the vital-breath’; ‘without the vital-breath’ means ‘abiding independently of the vital-breath’; and ‘without mind’ means ‘having knowledge not dependent on the mind’.

Or, else, the text: ‘All this, verily, is Brahman, emanating from him, disappearing into him, and breathing in him;—tranquil, let one meditate (on him) thus’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1) enjoins meditation, thus: ‘Let one meditate on Brahman, the soul of all, in a tranquil spirit The text: ‘Let him form a determination’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1) is a repetition (of the same injunction), with a view to proving that the attributes of ‘consisting of mind’ and the rest belong to the very same Being, mentioned above, (viz. Brahman). Let one meditate on Brahman, the soul of all and possessed of the attributes of consisting of mind and the rest,—this is the sense of the text. Here, a doubt arises, viz. whether Brahman, indicated as the soul of all, is the individual soul, or the Highest self. What is reasonable here? If it he suggested: The individual soul. Why? Because, it alone can possibly assume the forms of all kinds of beings, Brahma and so on, due to karmas, based on beginningless nescience; while it is never possible for the Supreme Brahman to assume identity with all sorts of low or vile forms, since He is endowed with (the attributes of) omniscience, omnipotence, freedom from sins, freed on by nature from all faults and so on. The word ‘Brahman’ too, applies to the individual soul alone, it being endowed with great qualities (like knowledge and the like). And the origin and the rest of the world being due to karmas, it is reasonable to indicate the individual soul as their cause,—

We reply: “Because of the teaching of what is celebrated everywhere”, i.e. the meaning of the word ‘Brahman,’ who is designated as the soul of all and as the cause of the origin and the rest of all, is the Highest Self alone. Bor this very reason, “everywhere”, i.e. in the Vedāntas, he is “taught” to be “celebrated” as the cause of the origin and the rest of the world—because of this; and also because it is impossible that the origin and the rest of the world can be due to the individual soul, since in the passages—“He desired: ‘May I be many, may I procreate’..... He created all this” (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.6) and so on, the Supreme Lord alone is celebrated to be the cause of the world. This is stated in the ‘Law of salvation’[6]. Beginning: ‘“Whence has arisen this entire world, consisting of the immovable and the movable, and to whom does it go during universal dissolution? Tell me that, O grandfather I By whom has this world, together with the oceans, the sky, mountains, cloud, lands, fire and air, been made?’” (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.6765-66[7]); having stated: ‘The scripture which was related by Bhṛgu to Bhāradvāja, who asked’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.6769C[8]); having stated the origin of all beings thus: ‘Of him who is called Nārāyaṇa, who is unchangeable, the imperishable sold, who is unmanifest, unknowable, higher than prakṛti;’[9] and having stated: ‘Then, a lustrous, celestial lotus was created by the self-born. From that lotus arose Brahma, the Lord, consisting of the Veda’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.6779C-89A[10]),—the text designates Lord Kṛṣṇa, Nārāyaṇa, Brahman, as the cause of all sentient beings and non-sentient objects, thus: ‘For he is difficult to be known, undoubtedly inconceivable in nature even by the perfected souls. He, verily, is Lord Viṣṇu, celebrated to be infinite, abiding as the inter controller of all beings, difficult to be known by those who have not obtained the self,—who is the creator of this principle of egoism for the production of all beings, from whom arose the universe, about whom I have been asked by you here’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.6784-86A[11]). Hence, the Highest Self alone is denoted by the word ‘Brahman’ here, and not the individual soul.[12]

Comparative views of Rāmānuja:

Reading same. He gives two alternative interpretations, which tally with the last two explanations of Śrīnivāsa.[13]

Footnotes and references:

[3]:

This passage occurs also in Śatapatha-brāhmaṇa 10.6.3. It forms a part of the famous Śāṇḍilya-vidyā, or the Doctrine of Śāṇḍilya. For a further account see footnote (5), p. 1078 f.

[4]:

‘Kṣetrajña’, means ‘Knower of the field’, or the body, i.e. the soul, the conscious principle in the corporeal frame.

[6]:

[7]:

P. 604, lines.3-4, vol. 3.

[8]:

op. cit., line 7.

[10]:

P. 604, lines 17-18 (vol. 3). This verse is not found in the Bombay edition.

[11]:

P. 604, lines 22-24.