Matangalila and Hastyayurveda (study)

by Chandrima Das | 2021 | 98,676 words

This page relates ‘Gajendra-Moksha (Gajendra’s salvation)’ of the study on the Matangalina and Hastyayurveda in the light of available epigraphic data on elephants in ancient India. Both the Matanga-Lila (by Nilakantha) and and the Hasti-Ayurveda (by Palakapya) represent technical Sanskrit works deal with the treatment of elephants. This thesis deals with their natural abode, capturing techniques, myths and metaphors, and other text related to elephants reflected from a historical and chronological cultural framework.

Gajendra-Mokṣa (Gajendra’s salvation)

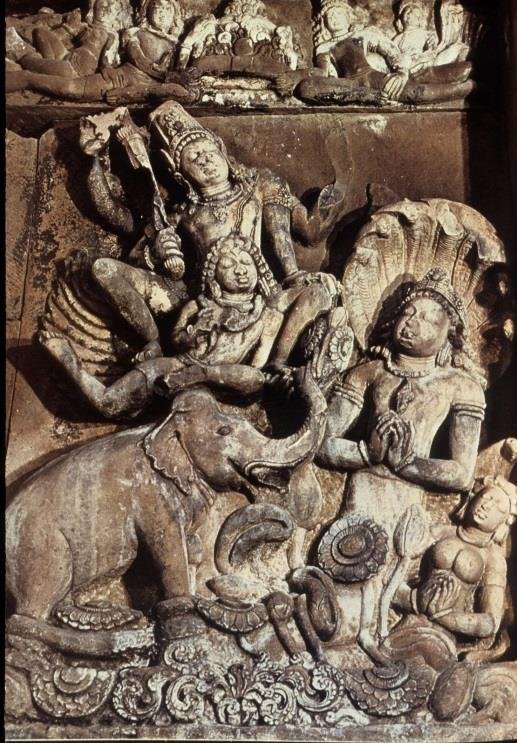

A twelfth century Cola balustrade in Dvārasamudra, Southern India, illustrate a tussle between the two creatures. At Gaṅgāikoṇḍacolapuram, an intriguing detail figures a giant snack devouring a tiny elephant; the symbolism behind the image remains elusive. Another fabulous monster is the shark like Gaja-Kūrmasin whose informs its favourite diet elephant and tortoise. The creature appetite is put to test in a Cālukya rendering at Pattadakal. Carved on to a column in the Virupākṣa temple the scene describes the climax of a well-known Puranic tell of piety and deliverance the Gajendra-Mokṣa (Gajendra’s salvation).[1]

[24. Gajendra-mokṣa]

Purāṇas narrate the story of Gaja-Kūrmasin or Kacchapa and both of these creatures got there forms due to curses casted on each other in a previous life. There was a sage called Bibhāvasu, who was very short tempered person. His younger brother Supratik often came to him and wanted the share of their father’s wealth. Bibhāvasu tried to make him understand. Then Supratik cursed Bibhāvasu that he may turn into an elephant. At that same time Bibhāvasu also cursed his brother that he may turn into a tortoise. Even in their newly acquired cursed bodies they did not forget their rivalry. They went to the forest where they continued the act of taking revenge.

One day the elephant plunged into a lake to drink water, the tortoise came and attacked him. The two struggled for an endless time. After many years Garuḍa came the place, he was seeking for the nectar. He was very hungry at that time, then he saw them. On the request of Kaśyapa muni, Garuḍa ate them. Thus two brothers got their salvation. Supratik became one of the Diggajas or elephants of cardinal points. The main theme of this narrative is mokṣa or salvation from evil power.

Even epigraphic records mention this story to indicate the king’s power which protected his country’s sovereignty from neighbouring kingdoms evil lustres.

For example Cintra Praśasti of the reign of Śāraṅgadeva elucidated the king thus–

“To his (Śāraṅgadhara) power he in reduce the powers of the Yādava and the Mālava lords, just as the lord bird formerly (overcome) the huge bodies elephant and the tortoise (v.13).”[2]

Two other records from Sinda and Benchamatti (Śaka 1088 and 1109) refer this Purāṇic story.[3]

The continuity of the narratives through a large span of time is quite significant and the presence of elephant in the narrative as the central character is noteworthy. The Gajendra mokṣa legend possibly represents a Purāṇic variation of the Ṛgvedic episode of Indra destroying Vṛtrāsura to liberate the rain clouds. Here, the elephant hero suggests a body of water rendered unsuitable for consumption by the presence of a “water monster”. Viṣṇu, who has replaced Indra in importance in the Purāṇas, is alone capable of reversing the situation to provide a remedy.

The rescue-scene emerges with quite grandeur on the Northern facade of the Daśāvatāra temple. The water-monster here is a nāga accompanied by his queen; the lotus pond is more evocative of a nest of mesmerised cobras. As Gajendra stands in their loosening coils, the nāga couple gazes heavenwards with hand folded in penitence. Viṣṇu’s expression is imperious, reminiscent of his features in the southern facade of the shrine, where other divinities had watched over his recumbent form. Here, a divine coronation awaits the elephant.[4]

Another interesting fact is the association of Gajendra with a typical kind of cloud. Puranic scholars have categorised these clouds into three classes, the first of those is “āgneya”. It originates from fire or heat or in other words evaporation. In a better sense they may be called cyclonic, thermal or clouds formed due to insolation. The Brahmāṇḍa Purāṇa explains that the āgneya clouds occurs in the winter season and assume the form of an elephant including a buffalo or boar being devoid of lightning and thunder (Vidyutguṇavihīnāḥ). These are of immense importance and are said to bring rainfall on the mountain foot within a radius of a krośa or a half (3 km. or 1.5 km).[5] It can be assumed that the clouds in elephant form might be hindered by some atmospheric reason that may have an adverse effect on the water resources. This atmospheric hindrance is depicted as the water-monster is the mythology. What is interesting is the fact that the elephants need water bodies for their survival and good health and their association with water, its evaporation and finally with clouds is the indication of the embedded concept of water cycle. The symbolism of these narratives has a much deeper insight.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Bhāgavata Purāṇa, Book VIII, Chapters 2-4.

[2]:

EI, Vol. I, p.272.

[3]:

Ibid., Vol. XX, p.118.

[4]:

V. Ram., p.43.