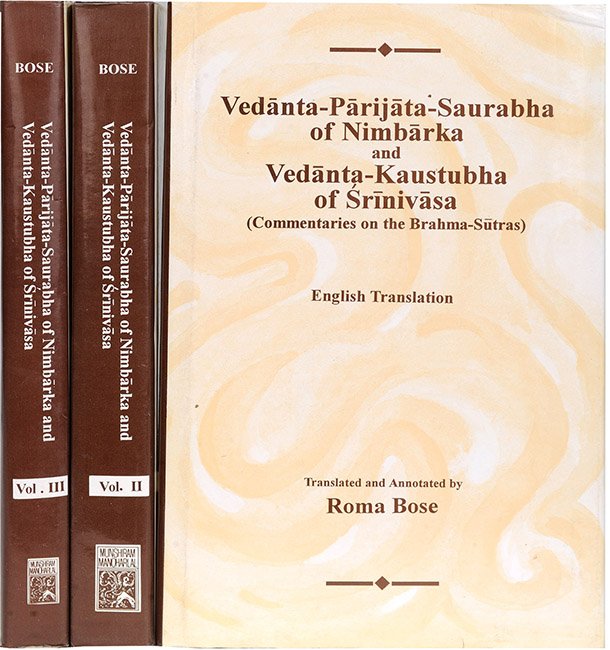

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.1.26 (correct conclusion, 26-30), including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.1.26 (correct conclusion, 26-30)

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.1.26 by Roma Bose:

“But (the above objection has no force) on account of scripture, since (the fact that brahman is the cause of the world is) based on scripture.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

The stated objection does not hold good. As the truth mentioned in the texts: ‘He wished “May I be many”’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.6[1]), ‘He Himself created Himself’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.7[2]), ‘He became existent and that’ (Tait. 2.6[3]), ‘So much is His greatness, higher than that is the Person’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.12.6[4]), ‘Just as a spider creates, so from the Person[5] the Universe originates’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.7[6]) and so on, is based on Scripture itself—anything else has no basis to stand upon.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

The author states the correct conclusion.

The word “but” is for disposing of the prima facie view. The entire Brahman is not transformed, nor is there any violation of texts. Why? “On account of Scripture.” That is, on account of the mass of texts which declare that Brahman is the non-different material and efficient cause of the world, different from the world, possessed of powers which are transformed and so on. Such scriptural texts are: ‘He wished “May I be many”’ (Tait, 2.6), ‘He Himself created Himself’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.7), ‘He became existent and that’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.6), ‘Having created it, he entered into that very thing’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.6), ‘That divinity thought: “Very well, let me enter into these three divinities’” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.3.2), ‘Having entered by this living soul’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6,3.2), ‘Who abiding within the earth,... from the earth does not know’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.7.3), ‘Entered within the ruler of men’ (Taittirīya-āraṇyaka 3.11.1, 2[7]), ‘So much is His greatness, higher than that is the Person’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.12.6) and so on. There is a Smṛti text as well, viz.: ‘Having voluntarily entered into prakṛti (matter) and puruṣa (soul), Hari shook the mutable and the immutable at the time of dissolution and creation’ (Viṣṇu-purāṇa 1.2.29[8]). Like a spider, Brahman is transformed into the form of the world, without waiting for external helpers. Hence there is no violation of the texts designating Him to he without parts. The scriptural text to this effect is as follows: ‘Just as a spider creates and takes, just as hairs on the head and body-hairs arise from a person, and medicinal herbs from the earth, so this universe arises from the Imperishable’ (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 1.1.7). There is a Smṛti text as well, viz.: ‘Just as a tortoise, having stretched out its limbs, again draws them in, so the Soul of beings, having created beings destroys them again’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.7072b-7073a[9]). Brahman, possessing the sentient and the non-sentient as His powers, is declared to be without parts and without limbs, because He has no parts and limbs as His material cause, as threads are of a piece of cloth.

If it he objected: If it be admitted that transformation means the projection of power, then there being no transformation of the real nature of the creator, what is the difference of this view from the views of the Sāṃkhyas and the rest?[10]—(we reply:) Listen. The Sāṃkhyas hold that the material cause of the world is a substance which is different from the puruṣa (or the soul) just as a lump of clay is different from a potter, which does not possess it (viz.: puruṣa) as its soul, and which is possessed of independent existence and activity. But Brahman, as admitted by the Vedantins, is One alone. He transforms Himself into the form of non-sentient objects like the ether and the rest by projecting His power of the enjoyed (i.e. the acit-śakti); having projected the sentient power of the enjoyer (i.e. the cit-śakti) in the form of gods and the rest, and having entered within as their inner controller, makes them undergo the fruits of their respective works; and contracts them during the time of dissolution, as a tortoise does its limbs, and the sun its rays.

To the objection, viz. even if there be the collection of external helpers by Brahman, no contradiction arises in the case in hand; and hence pradhāna, established by the Tantra may be the external implement, suitable for the production of the world, just as clay is for the production of a pot. What is the use of a transformation consisting in the projection of powers?—the author replies: On this view, there will be contradiction of scriptural texts. This he says in the words: “Because of being based on Scripture”. Transformation consisting in the projection of powers is accepted, based as it is on Scripture. If implements like pradhāna and the rest be admitted, that view will have no basis to stand upon; and the consequence will be that Brahman will have to depend on another for His creation, Further, the following texts will come to be contradicted, viz. ‘All this has that for its soul’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.7 ch.), ‘All this, verily, is Brahman’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1), ‘Which being known, all comes to be known’ and so on,—this is the sense.

Comparative views of Śaṃkara:

This is sūtra 27 in his commentary. Interpretation same, but he adds his usual explanation in conclusion that from the transcendental point of view, no question of creation arises at all and hence no question as to how, Brahman, who is partless is yet not transformed in His entirety.[11]

Comparative views of Rāmānuja:

Interpretation of the word “śabda-mūlatvāt” different,—viz. (The fact that Brahman is possessed of various powers) is based on Scripture.[12] According to Nimbārka, it means, as we have seen, “(The fact that Brahman creates the world, yet remains untransformed) is based on Scripture”[13]; while according to Śrīnivāsa: (The fact that transformation means nothing but projection of powers) is based on Scripture.

Comparative views of Baladeva:

This is sūtra 27 in his commentary, viz. “(But the above objection does not apply to the case of the Lord, the real creator) on account of Scripture, because (the knowledge of Brahman) is based on Scripture”.[14]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Not quoted by others.

[2]:

Op. cit.

[3]:

Op. cit.

[6]:

Not quoted by others.

[7]:

P. 191.

[8]:

P. 16.

[9]:

P. 615, lines 24-25, vol, 3. Reading: “sṛṣṭāni karate”. Vaṅgavāsī ed., also p. 1571.

[10]:

I.e. according to the Sāṃkhyas, pradhāna is transformed into the world, while according to the Vedāntins also not Brahman Himself, but His power of the non-sentient (acicchakti)—which is pradhāna—is transformed into the world. Hence the two views come to the same thing.

[11]:

Brahma-sūtras (Śaṅkara’s commentary) 2.1.27, p. 491.

[13]:

This is the interpretation of Śaṅkara as well.