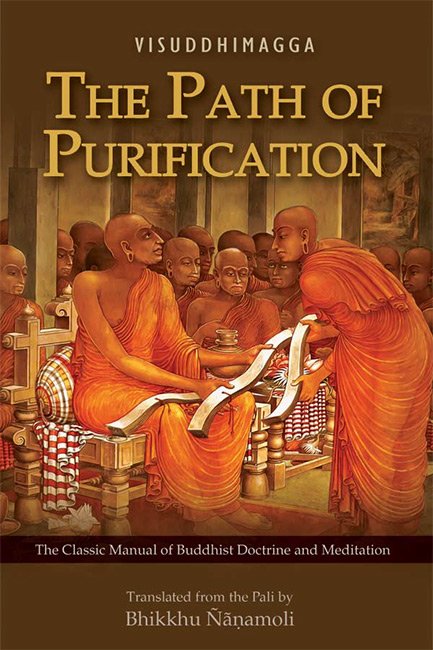

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes Note regarding pannatti (concept) of the section Other Recollections as Meditation Subjects of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

Note regarding paññatti (concept)

Twenty-four kinds are dealt with in the commentary to the Puggalapaññatti.

The Puggalapaññatti Schedule (mātikā) gives the following six paññatti (here a making known, a setting out):

- of aggregates,

- bases,

- elements,

- truths,

- faculties, and

- persons. (Pug 1)

The commentary explains the word in this sense as paññāpana (making known) and ṭhapana (placing), quoting “He announces, teaches, declares (paññāpeti), establishes” (cf. M III 248), and also “a well-appointed (supaññatta) bed and chair” (?).

It continues:

“The making known of a name (nāma-paññatti) shows such and such dhammas and places them in such and such compartments, while the making known of the aggregates (khandha-paññatti) and the rest shows in brief the individual form of those making-known (paññatti).”

It then gives six kinds of paññatti “according to the commentarial method but not in the texts”:

(1) Concept of the existent (vijjamāna-paññatti), which is the conceptualizing of (making known) a dhamma that is existent, actual, become, in the true and ultimate sense (e.g. aggregates, etc.).

(2) Concept of the non-existent, which is, for example, the conceptualizing of “female,” “male,” “persons,” etc., which are non-existent by that standard and are only established by means of current speech in the world; similarly “such impossibilities as concepts of a fifth truth or the other sectarians’ Atom, Primordial Essence, World Soul, and the like.”

(3) Concept of the non-existent based on the existent, e.g. the expression, “One with the three clear-visions,” where the “person” (“one”) is nonexistent and the “clear-visions” are existent.

(4) Concept of the existent based on the non-existent, e.g. the “female form,” “visible form” (= visible datum base) being existent and “female” non-existent.

(5) Concept of the existent based on the existent, e.g. “eye-contact,” both “eye” and “contact” being existent.

(6) Concept of the non-existent based on the non-existent, e.g. “banker’s son,” both being non-existent.

Again two more sets of six are given as “according to the Teachers, but not in the Commentaries.” The first is:

(1) Derivative concept (upādā-paññatti); this, for instance, is a “being,” which is a convention derived from the aggregates of materiality, feeling, etc., though it has no individual essence of its own apprehendable in the true ultimate sense, as materiality, say, has in its self-identity and its otherness from feeling, etc.; or a “house” or a “fist” or an “oven” as apart from its component parts, or a “pitcher” or a “garment,” which are all derived from those same aggregates; or “time” or “direction,” which are derived from the revolutions of the moon and sun; or the “learning sign” or “counterpart sign” founded on some aspect or other, which are a convention derived from some real sign as a benefit of meditative development: these are derived concepts, and this kind is a “concept” (paññatti) in the sense of “ability to be set up” (paññāpetabba = ability to be conceptualized), but not in the sense of “making known” (paññāpana). Under the latter heading this would be a “concept of the nonexistent.”

(2) Appositional concept (upa-nidhā-paññatti): many varieties are listed, namely, apposition of reference (“second” as against “first,” “third” as against “second,” “long” as against “short”); apposition of what is in the hand (“umbrella-in-hand,” “knife-in-hand”); apposition of association (“earring-wearer,” “topknot-wearer,” “crest-wearer”); apposition of contents (“corn-wagon,” “ghee-pot”); apposition of proximity (“Indasālā Cave,” “Piyaṅgu Cave”); apposition of comparison (“golden coloured,” “with a bull’s gait”); apposition of majority (“Padumassara-brahman Village”); apposition of distinction (“diamond ring”); and so on.

(3) Collective concept (samodhāna-paññatti), e.g., “eight-footed,” “pile of riches.”

(4) Additive concept (upanikkhitta-paññatti), e.g. “one,” “two,” “three.”

(5) Verisimilar concept (tajjā-paññatti): refers to the individual essence of a given dhamma, e.g. “earth,” “fire,” “hardness,” “heat.”

(6) Continuity concept (santati-paññatti): refers to the length of continuity of life, e.g. “octogenarian,” “nonagenarian.”

In the second set there are:

(i) Concept according to function (kicca-paññatti), e.g. “preacher,” “expounder of Dhamma.”

(ii) Concept according to shape (saṇṭhāna-paññatti), e.g. “thin,” “stout,” “round,” “square.”

(iii) Concept according to gender (liṅga-paññatti), e.g. “female,” “male.”

(iv) Concept according to location (bhūmi-paññatti), e.g. “of the sense sphere,” “Kosalan.”

(v) Concept as proper name (paccatta-paññatti), e.g. “Tissa,” “Nāga,” “Sumana,” which are making-known (appellations) by mere name-making.

(vi) Concept of the unformed (asaṅkhata-paññatti), e.g. “cessation,” “Nibbāna,” etc., which make the unformed dhamma known—an existent concept. (From commentary to Puggalapaññatti, condensed—see also Dhs-a 390f.)

All this shows that the word paññatti carries the meanings of either appellation or concept or both together, and that no English word quite corresponds.