Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Many Monks which is verse 315 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 315 is part of the Niraya Vagga (Hell) and the moral of the story is “Guard oneself like a border town, against evils’ onslaught. Neglect here leads one to ruin”.

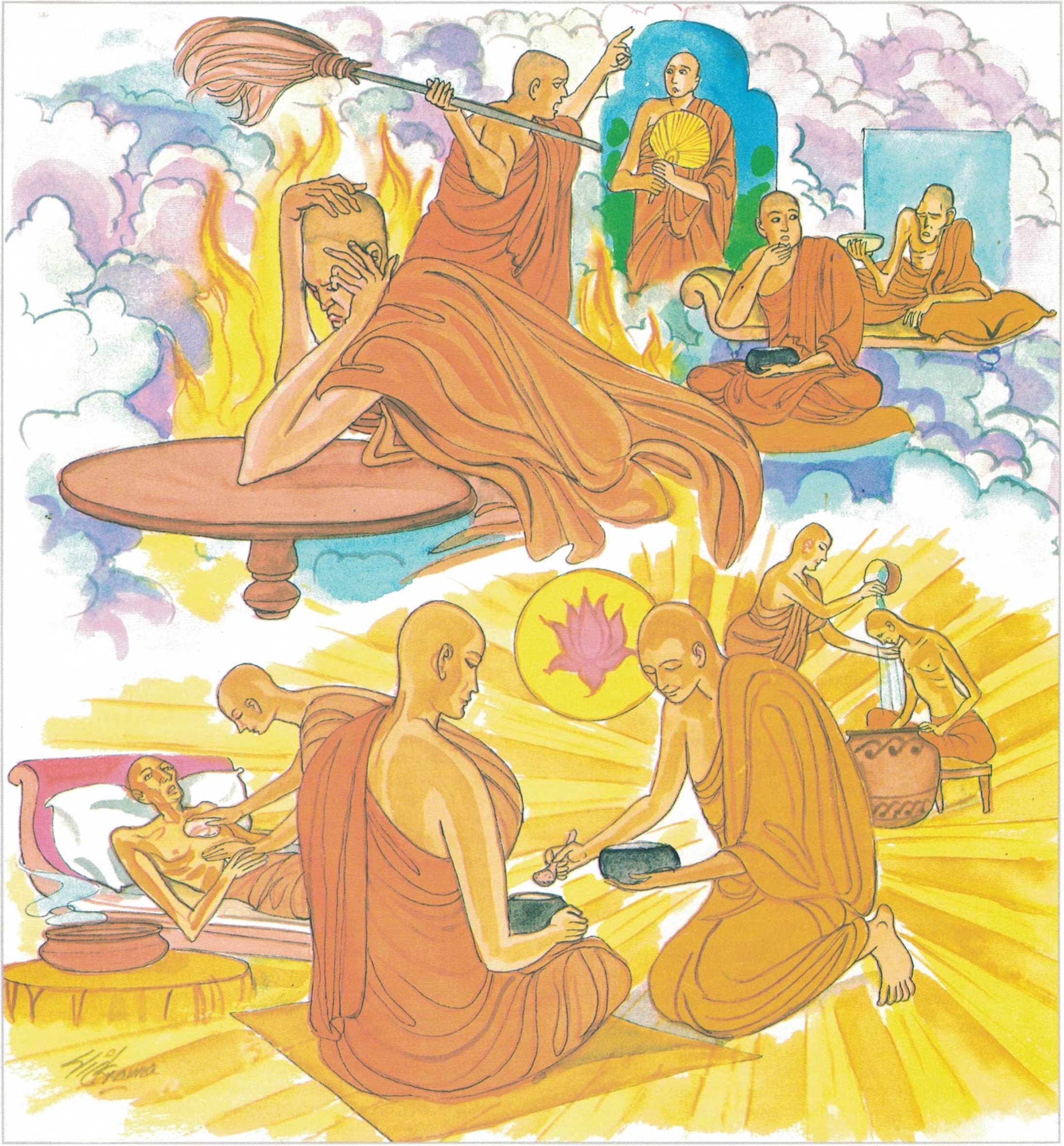

Verse 315 - The Story of Many Monks

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 315:

nagaraṃ yathā paccantaṃ guttaṃ santarabāhiraṃ |

evaṃ gopetha attānaṃ khaṇo ve mā upaccagā |

khaṇātītā hi socanti nirayamhi samappitā || 315 ||

315. Even as a border town guarded within and without, so should you protect yourselves. Do not let this moment pass for when this moment’s gone they grieve sending themselves to hell.

Guard oneself like a border town, against evils’ onslaught. Neglect here leads one to ruin. |

The Story of Many Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to a group of monks who spent the rainy season in a border town.

In the first month of their stay in that border town, the monks were well provided for and well looked after by the townsfolk. During the next month the town was plundered by some robbers and some people were taken away as hostages. The people of the town, therefore, had to rehabilitate their town and reinforce fortifications. Thus, they were unable to look to the needs of the monks as much as they would have liked to and the monks had to fend for themselves. At the end of the rainy season, those monks came to pay homage to the Buddha at the Jetavana Monastery in Sāvatthi. On learning about the hardships they had undergone during the raining season, the Buddha said to them, “Monks, do not keep thinking about this or anything else; it is always difficult to have a carefree, effortless life. Just as the townsfolk guard their town, so also, a monk should be on guard and keep his mind steadfastly on his body.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 315)

paccantaṃ santarabāhiraṃ guttaṃ nagaraṃ yathā,

evaṃ attānaṃ gopetha hi khaṇātītā nirayamhi

samappitā samappita socanti khaṇo ve mā upaccagā

paccantaṃ [paccanta]: situated at the frontier; santarabāhiraṃ [santarabāhira]: within and without; guttaṃ [gutta]: protected; nagaraṃ [nagara]: a city; yathā evaṃ: just like (that); attānaṃ [attāna]: one’s mind; gopetha: protect; hi: if for some reason; khaṇātītā: a moment passes; nirayamhi: in hell; samappitā: having been born; socanti: one may repent; khaṇo [khaṇa]: (therefore) the moment; ve: certainly; mā upaccagā: do not allow to escape–do not throw away

As a border town is guarded both inside and outside, so guard yourself. Let not the right moment go by. Those who miss this moment will come to grief when they fall into hell.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 315)

In this verse the Buddha’s advice is to guard one’s mind just as rulers would guard a border town. The guarding of the mind comes within the field of mind concentration–bhāvanā–meditation, the central purpose of which is perpetual alertness of mind.

The Buddhist theory of meditation aims at the practice of right concentration (sammā-samādhi), the culmination of the noble eightfold path which is expounded for the first time in the Buddha’s inaugural sermon, known as ‘Dhammacakkappavattana’, the ‘Turning of the Wheel of the Doctrine.’ The noble eight-fold path as the method of self-enlightenment, which is the goal of Buddhist doctrine, is called majjhimā paṭipadā, the middle path. It is so called because it tends to moderation, avoiding the two extremes: On the one hand, of indulgence in sense pleasures, and on the other, of adherence to the practices of self-mortification.

Hence the practice of this method is a median between the two extremes, avoiding all excess. Excess in any direction must be avoided as it is dangerous. Buddhist meditation, therefore, cannot be practiced by the worldly man, who is unwilling to reduce his worldly desires, nor is it possible for one who is a fanatic in ascetic practices. In order to observe moderation it is necessary to have strength on the one side, and thoughtfulness on the other. So we find in the formula of the path that right concentration is well supported by the two principles of right effort and right mindfulness. Of these, right effort promotes the ability to rise in one who is prone to sink into sensual pleasure;while right mindfulness becomes a safeguard against falling into extremes of asceticism.

Right concentration is not possible without that moral purity which purges one of impure deeds, words and thoughts, and therefore it presupposes right speech, right action and right livelihood. These are the three principles of sīla or moral purity, which is necessarily the preparatory ground to meditation. The training in these principles is the most fundamental aspect of Buddhism and forms the vital factor in contemplative life. Hence, first of all, one must school himself in moral purity in accordance with the rules of the middle path, in order to attain full and immediate results of meditation in an ascending scale of progress. The disciple who conforms himself to these ideals will acquire self-confidence, inward purity, absence of external fear, and thereby mental serenity, factors which are imperative for ultimate success in meditation.