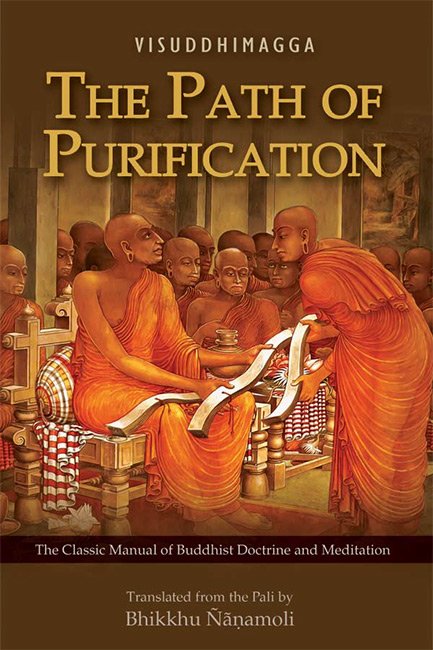

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes (4) Equanimity of the section The Divine Abidings (Brahmavihāra-niddesa) of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

(4) Equanimity

88. One who wants to develop equanimity must have already obtained the triple or quadruple jhāna in loving-kindness, and so on. He should emerge from the third jhāna [in the fourfold reckoning], after he has made it familiar, and he should see danger in the former [three divine abidings] because they are linked with attention given to beings’ enjoyment in the way beginning “May they be happy,” because resentment and approval are near, and because their association with joy is gross. And he should also see the advantage in equanimity because it is peaceful. Then he should arouse equanimity (upekkhā) by looking on with equanimity (ajjhupekkhitvā) at a person who is normally neutral; after that at a dear person, and the rest. For this is said: “And how does a bhikkhu dwell pervading one direction with his heart endued with equanimity? Just as he would feel equanimity on seeing a person who was neither beloved nor unloved, so he pervades all beings with equanimity” (Vibh 275).

89. Therefore he should arouse equanimity towards the neutral person in the way already stated. Then, through the neutral one, he should break down the barriers in each case between the three people, that is, the dear person, then the boon companion, and then the hostile one, and lastly himself. And he should cultivate that sign, develop and repeatedly practice it.

90. As he does so the fourth jhāna arises in him in the way described under the earth kasiṇa.

But how then? Does this arise in one in whom the third jhāna has already arisen on the basis of the earth kasiṇa, etc.? It does not. Why not? Because of the dissimilarity of the object. It arises only in one in whom the third jhāna has arisen on the basis of loving-kindness, etc., because the object is similar.

But after that the versatility and the obtaining of advantages should be understood in the same way as described under loving-kindness.

This is the detailed explanation of the development of equanimity.

[General]

91.

Now, having thus known these divine abidings

Told by the Divine One (brahmā) supremely [wise],

There is this general explanation too

Concerning them that he should recognize.

[Meanings]

92. Now, as to the meaning firstly of loving-kindness, compassion, gladness and equanimity: it fattens (mejjati), thus it is loving-kindness (mettā); it is solvent (siniyhati) is the meaning. Also: it comes about with respect to a friend (mitta), [318] or it is behaviour towards a friend, thus it is loving-kindness (mettā).

When there is suffering in others it causes (karoti) good people’s hearts to be moved (kampana), thus it is compassion (karuṇā). Or alternatively, it combats (kiṇāti)[1] others’ suffering, attacks and demolishes it, thus it is compassion. Or alternatively, it is scattered (kiriyati) upon those who suffer, it is extended to them by pervasion, thus it is compassion (karuṇā).

Those endowed with it are glad (modanti), or itself is glad (modati), or it is the mere act of being glad (modana), thus it is gladness (muditā).

It looks on at (upekkhati), abandoning such interestedness as thinking “May they be free from enmity” and having recourse to neutrality, thus it is equanimity (upekkhā).

[Characteristic, Etc.]

93. As to the characteristic, etc., loving-kindness is characterized here as promoting the aspect of welfare. Its function is to prefer welfare. It is manifested as the removal of annoyance. Its proximate cause is seeing loveableness in beings. It succeeds when it makes ill will subside, and it fails when it produces (selfish) affection.

94. Compassion is characterized as promoting the aspect of allaying suffering. Its function resides in not bearing others’ suffering. It is manifested as noncruelty. Its proximate cause is to see helplessness in those overwhelmed by suffering. It succeeds when it makes cruelty subside and it fails when it produces sorrow.

95. Gladness is characterized as gladdening (produced by others’ success).[2] Its function resides in being unenvious. It is manifested as the elimination of aversion (boredom). Its proximate cause is seeing beings, success. It succeeds when it makes aversion (boredom) subside, and it fails when it produces merriment.

96. Equanimity is characterized as promoting the aspect of neutrality towards beings. Its function is to see equality in beings. It is manifested as the quieting of resentment and approval. Its proximate cause is seeing ownership of deeds (kamma) thus: “Beings are owners of their deeds. Whose[3] [if not theirs] is the choice by which they will become happy, or will get free from suffering, or will not fall away from the success they have reached?” It succeeds when it makes resentment and approval subside, and it fails when it produces the equanimity of unknowing, which is that [worldly-minded indifference of ignorance] based on the house life.

[Purpose]

97. The general purpose of these four divine abidings is the bliss of insight and an excellent [form of future] existence. That peculiar to each is respectively the warding off of ill will, and so on. For here loving-kindness has the purpose of warding off ill will, while the others have the respective purposes of warding off cruelty, aversion (boredom), and greed or resentment. And this is said too: “For this is the escape from ill will, friends, that is to say, the mind-deliverance of loving-kindness … For this is the escape from cruelty, friends, that is to say, the mind-deliverance of compassion … For this is the escape from boredom, friends, that is to say, the mind-deliverance of gladness … For this is the escape from greed, friends, that is to say, the mind-deliverance of equanimity” (D III 248).

[The Near and Far Enemies]

98. And here each one has two enemies, one near and one far.

The divine abiding of loving-kindness [319] has greed as its near enemy,[4] since both share in seeing virtues. Greed behaves like a foe who keeps close by a man, and it easily finds an opportunity. So loving-kindness should be well protected from it. And ill will, which is dissimilar to the similar greed, is its far enemy like a foe ensconced in a rock wilderness. So loving-kindness must be practiced free from fear of that; for it is not possible to practice loving-kindness and feel anger simultaneously (see D III 247–48).

99. Compassion has grief based on the home life as its near enemy, since both share in seeing failure. Such grief has been described in the way beginning, “When a man either regards as a privation failure to obtain visible objects cognizable by the eye that are sought after, desired, agreeable, gratifying and associated with worldliness, or when he recalls those formerly obtained that are past, ceased and changed, then grief arises in him. Such grief as this is called grief based on the home life” (M III 218). And cruelty, which is dissimilar to the similar grief, is its far enemy. So compassion must be practiced free from fear of that; for it is not possible to practice compassion and be cruel to breathing things simultaneously.

100. Gladness has joy based on the home life as its near enemy, since both share in seeing success. Such joy has been described in the way beginning, “When a man either regards as gain the obtaining of visible objects cognizable by the eye that are sought … and associated with worldliness, or recalls those formerly obtained that are past, ceased, and changed, then joy arises in him. Such joy as this is called joy based on the home life” (M III 217). And aversion (boredom), which is dissimilar to the similar joy, is its far enemy. So gladness should be practiced free from fear of that; for it is not possible to practice gladness and be discontented with remote abodes and things connected with the higher profitableness simultaneously.

101. Equanimity has the equanimity of unknowing based on the home life as its near enemy, since both share in ignoring faults and virtues. Such unknowing has been described in the way beginning, “On seeing a visible object with the eye equanimity arises in the foolish infatuated ordinary man, in the untaught ordinary man who has not conquered his limitations, who has not conquered future [kamma] result, who is unperceiving of danger. Such equanimity as this does not surmount the visible object. Such equanimity as this is called equanimity based on the home life” (M III 219). And greed and resentment, which are dissimilar to the similar unknowing, are its far enemies. Therefore equanimity must be practiced free from fear of that; [320] for it is not possible to look on with equanimity and be inflamed with greed or be resentful[5] simultaneously.

[The Beginning, Middle and End, Etc.]

102. Now, zeal consisting in desire to act is the beginning of all these things. Suppression of the hindrances, etc., is the middle. Absorption is the end. Their object is a single living being or many living beings, as a mental object consisting in a concept.

[The Order in Extension]

103. The extension of the object takes place either in access or in absorption. Here is the order of it. Just as a skilled ploughman first delimits an area and then does his ploughing, so first a single dwelling should be delimited and lovingkindness developed towards all beings there in the way beginning, “In this dwelling may all beings be free from enmity.” When his mind has become malleable and wieldy with respect to that, he can then delimit two dwellings. Next he can successively delimit three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten, one street, half the village, the whole village, the district, the kingdom, one direction, and so on up to one world-sphere, or even beyond that, and develop lovingkindness towards the beings in such areas. Likewise with compassion and so on. This is the order in extending here.

[The Outcome]

104. Just as the immaterial states are the outcome of the kasiṇas, and the base consisting of neither perception nor non-perception is the outcome of concentration, and fruition attainment is the outcome of insight, and the attainment of cessation is the outcome of serenity coupled with insight, so the divine abiding of equanimity is the outcome of the first three divine abidings. For just as the gable rafters cannot be placed in the air without having first set up the scaffolding and built the framework of beams, so it is not possible to develop the fourth (jhāna in the fourth divine abiding) without having already developed the third jhāna in the earlier (three divine abidings).

[Four Questions]

105. And here it may be asked: But why are loving-kindness, compassion, gladness, and equanimity, called divine abidings? And why are they only four? And what is their order? And why are they called measureless states in the Abhidhamma?

106. It may be replied: The divineness of the abiding (brahmavihāratā) should be understood here in the sense of best and in the sense of immaculate. For these abidings are the best in being the right attitude towards beings. And just as Brahmā gods abide with immaculate minds, so the meditators who associate themselves with these abidings abide on an equal footing with Brahmā gods. So they are called divine abidings in the sense of best and in the sense of immaculate. [321]

107. Here are the answers to the questions beginning with “Why are they only four?”:

Their number four is due to paths to purity

And other sets of four; their order to their aim

As welfare and the rest. Their scope is found to be

Immeasurable, so “measureless states” their name.

108. For among these, loving-kindness is the way to purity for one who has much ill will, compassion is that for one who has much cruelty, gladness is that for one who has much aversion (boredom), and equanimity is that for one who has much greed. Also attention given to beings is only fourfold, that is to say, as bringing welfare, as removing suffering, as being glad at their success, and as unconcern, [that is to say, impartial neutrality]. And one abiding in the measureless states should practice loving-kindness and the rest like a mother with four sons, namely, a child, an invalid, one in the flush of youth, and one busy with his own affairs; for she wants the child to grow up, wants the invalid to get well, wants the one in the flush of youth to enjoy for long the benefits of youth, and is not at all bothered about the one who is busy with his own affairs. That is why the measureless states are only four as “due to paths to purity and other sets of four.”

109. One who wants to develop these four should practice them towards beings first as the promotion of the aspect of welfare—and loving-kindness has the promotion of the aspect of welfare as its characteristic; and next, on seeing or hearing or judging[6] that beings whose welfare has been thus wished for are at the mercy of suffering, they should be practiced as the promotion of the aspect of the removal of suffering—and compassion has the promotion of the aspect of the removal of suffering as its characteristic; and then, on seeing the success of those whose welfare has been wished for and the removal of whose suffering has been wished for, they should be practiced as being glad—and gladness has the act of gladdening as its characteristic; but after that there is nothing to be done and so they should be practiced as the neutral aspect, in other words, the state of an onlooker—and equanimity has the promotion of the aspect of neutrality as its characteristic; therefore, since their respective aims are the aspect of welfare, etc., their order should be understood to correspond, with lovingkindness stated first, then compassion, gladness and equanimity.

110. All of them, however, occur with a measureless scope, for their scope is measureless beings; and instead of assuming a measure such as “Lovingkindness, etc., should be developed only towards a single being, or in an area of such an extent,” they occur with universal pervasion.

That is why it was said: [322]

Their number four is due to paths to purity

And other sets of four; their order to their aim

As welfare and the rest. Their scope is found to be

Immeasurable, so “measureless states” their name.

[As Producing Three Jhānas and Four Jhānas]

111. Though they have a single characteristic in having a measureless scope, yet the first three are only of triple and quadruple jhāna [respectively in the fourfold and fivefold reckonings]. Why? Because they are not dissociated from joy. But why are their aims not dissociated from joy? Because they are the escape from ill will, etc., which are originated by grief. But the last one belongs only to the remaining single jhāna. Why? Because it is associated with equanimous feeling. For the divine abiding of equanimity that occurs in the aspect of neutrality towards beings does not exist apart from equanimous [that is to say, neitherpainful-nor-pleasant] feeling.

112. However, someone might say this: “It has been said by the Blessed One in the Book of Eights, speaking of the measureless states in general: ‘Next, bhikkhu, you should develop the concentration with applied thought and sustained thought, and you should develop it without applied thought and with sustained thought only, and you should develop it without applied thought and without sustained thought, and you should develop it with happiness, and you should develop it without happiness, and you should develop it accompanied by gratification, and you should develop it accompanied by equanimity’ (A IV 300). Consequently all four measureless states have quadruple and quintuple jhāna.”

113. He should be told: “Do not put it like that. For if that were so, then contemplation of the body, etc., would also have quadruple and quintuple jhāna. But there is not even the first jhāna in the contemplation of feeling or in the other two.[7] So do not misrepresent the Blessed One by adherence to the letter. The Enlightened One’s word is profound and should be taken as it is intended, giving due weight to the teachers.”

114. And the intention here is this: The Blessed One, it seems, was asked to teach the Dhamma thus: “Venerable sir, it would be good if the Blessed One would teach me the Dhamma in brief, so that, having heard the Blessed One’s Dhamma, I may dwell alone, withdrawn, diligent, ardent and self-exerted” (A IV 299). But the Blessed One had no confidence yet in that bhikkhu, since although he had already heard the Dhamma he had nevertheless gone on living there instead of going to do the ascetic’s duties, [and the Blessed One expressed his lack of confidence] thus: “So too, some misguided men merely question me, and when the Dhamma is expounded [to them], they still fancy that they need not follow me” (A IV 299). However, the bhikkhu had the potentiality for the attainment of Arahantship, and so he advised him again, [323] saying: “Therefore, bhikkhu, you should train thus: ‘My mind shall be steadied, quite steadied internally, and arisen evil unprofitable things shall not obsess my mind and remain.’ You should train thus” (A IV 299). But what is stated in that advice is basic concentration consisting in mere unification of mind[8] internally in the sense of in oneself (see Ch. XIV, n. 75).

115. After that he told him about its development by means of loving-kindness in order to show that he should not rest content with just that much but should intensify his basic concentration in this way: “As soon as your mind has become steadied, quite steadied internally, bhikkhu, and arisen evil unprofitable things do not obsess your mind and remain, then you should train thus: ‘The minddeliverance of loving-kindness will be developed by me, frequently practiced, made the vehicle, made the foundation, established, consolidated, and properly undertaken.’ You should train thus, bhikkhu” (A IV 299–300), after which he said further: “As soon as this concentration has been thus developed by you, bhikkhu,[9] and frequently practiced, then you should develop this concentration with applied thought and sustained thought … and you should develop it accompanied by equanimity” (A IV 300).

116. The meaning is this: “Bhikkhu, when this basic concentration has been developed by you by means of loving-kindness, then, instead of resting content with just that much, you should make this basic concentration reach quadruple and quintuple jhāna in other objects by [further] developing it in the way beginning ‘With applied thought.’”

117. And having spoken thus, he further said: “As soon as this concentration has been thus developed by you, bhikkhu, and frequently practiced, then you should train thus: ‘The mind-deliverance of compassion will be developed by me …’ (A IV 300), etc., pointing out that “you should effect its [further] development by means of quadruple and quintuple jhāna in other objects, this [further] development being preceded by the remaining divine abidings of compassion and the rest.”

118. Having thus shown how its [further] development by means of quadruple and quintuple jhāna is preceded by loving-kindness, etc., and having told him, “As soon as this concentration has been developed by you, bhikkhu, and frequently practiced, then you should train thus: ‘I shall dwell contemplating the body as a body,’” etc., he concluded the discourse with Arahantship as its culmination thus: “As soon as this concentration has been developed by you, bhikkhu, completely developed, then wherever you go you will go in comfort, wherever you stand you will stand in comfort, wherever [324] you sit you will sit in comfort, wherever you make your couch you will do so in comfort” (A IV 301). From that it must be understood that the [three] beginning with loving-kindness have only triple-quadruple jhāna, and that equanimity has only the single remaining jhāna. And they are expounded in the same way in the Abhidhamma as well.

[The Highest Limit of Each]

119. And while they are twofold by way of the triple-quadruple jhāna and the single remaining jhāna, still they should be understood to be distinguishable in each case by a different efficacy consisting in having “beauty as the highest,” etc. For they are so described in the Haliddavasana Sutta, according as it is said: “Bhikkhus, the mind-deliverance of loving-kindness has beauty as the highest, I say … The mind-deliverance of compassion has the base consisting of boundless space as the highest, I say … The mind-deliverance of gladness has the base consisting of boundless consciousness as the highest I say … The minddeliverance of equanimity has the base consisting of nothingness as the highest, I say” (S V 119–21).[10]

120. But why are they described in this way? Because each is the respective basic support for each. For beings are unrepulsive to one who abides in lovingkindness. Being familiar with the unrepulsive aspect, when he applies his mind to unrepulsive pure colours such as blue-black, his mind enters into them without difficulty. So loving-kindness is the basic support for the liberation by the beautiful (see M II 12; M-a III 256), but not for what is beyond that. That is why it is called “having beauty as the highest.”

121. One who abides in compassion has come to know thoroughly the danger in materiality, since compassion is aroused in him when he sees the suffering of beings that has as its material sign (cause) beating with sticks, and so on. So, well knowing the danger in materiality, when he removes whichever kasiṇa [concept he was contemplating], whether that of the earth kasiṇa or another, and applies his mind to the space [that remains (see X.6)], which is the escape from materiality, then his mind enters into that [space] without difficulty. So compassion is the basic support for the sphere of boundless space, but not for what is beyond that. That is why it is called “having the base consisting of boundless space as the highest.”

122. When he abides in gladness, his mind becomes familiar with apprehending consciousness, since gladness is aroused in him when he sees beings’ consciousness arisen in the form of rejoicing over some reason for joy. Then when he surmounts the sphere of boundless space that he had already attained in due course and applies his mind to the consciousness that had as its object the sign of space, [325] his mind enters into it without difficulty. So gladness is the basic support for the base consisting of boundless consciousness, but not for what is beyond that. That is why it is called “having the sphere of boundless consciousness as the highest.”

123. When he abides in equanimity, his mind becomes skilled[11] in apprehending what is (in the ultimate sense) non-existent, because his mind has been diverted from apprehension of (what is existent in) the ultimate sense, namely, pleasure, (release from) pain, etc., owing to having no further concern such as “May beings be happy” or “May they be released from pain” or “May they not lose the success they have obtained.” Now his mind has become used to being diverted from apprehension of [what is existent in] the ultimate sense, and his mind has become skilled in apprehending what is non-existent in the ultimate sense, (that is to say, living beings, which are a concept), and so when he surmounts the base consisting of boundless consciousness attained in due course and applies his mind to the absence, which is non-existent as to individual essence, of consciousness, which is a reality (is become—see M I 260) in the ultimate sense, then his mind enters into that (nothingness, that non-existence) without difficulty (see X.32). So equanimity is the basic support for the base consisting of nothingness, but not for what is beyond that. That is why it is called “having the base consisting of nothingness as the highest.”

124. When he has understood thus that the special efficacy of each resides respectively in “having beauty as the highest,” etc., he should besides understand how they bring to perfection all the good states beginning with giving. For the Great Beings’ minds retain their balance by giving preference to beings’ welfare, by dislike of beings’ suffering, by desire for the various successes achieved by beings to last, and by impartiality towards all beings. And to all beings they give gifts, which are a source a pleasure, without discriminating thus: “It must be given to this one; it must not be given to this one.” And in order to avoid doing harm to beings they undertake the precepts of virtue. They practice renunciation for the purpose of perfecting their virtue. They cleanse their understanding for the purpose of non-confusion about what is good and bad for beings. They constantly arouse energy, having beings’ welfare and happiness at heart. When they have acquired heroic fortitude through supreme energy, they become patient with beings’ many kinds of faults. They do not deceive when promising “We shall give you this; we shall do this for you.” They are unshakably resolute upon beings’ welfare and happiness. Through unshakable loving-kindness they place them first [before themselves]. Through equanimity they expect no reward. Having thus fulfilled the [ten] perfections, these [divine abidings] then perfect all the good states classed as the ten powers, the four kinds of fearlessness, the six kinds of knowledge not shared [by disciples], and the eighteen states of the Enlightened One.[12] This is how they bring to perfection all the good states beginning with giving.

The ninth chapter called “The Description of the Divine Abidings” in the Treatise on the Development of Concentration in the Path of Purification composed for the purpose of gladdening good people.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Kiṇāti—“it combats”: Skr. kºnāti—to injure or kill. PED gives this ref. under ordinary meaning “to buy,” which is wrong.

[2]:

So Vism-mhṭ 309.

[3]:

All texts read kassa (whose), which is confirmed in the quotation translated in note 20. It is tempting, in view of the context, to read kammassa (kamma’s), but there is no authority for it. The statement would then be an assertion instead of a question.

[4]:

“Greed is the near enemy of loving-kindness since it is able to corrupt owing to its similarity, like an enemy masquerading as a friend” (Vism-mhṭ 309).

[5]:

Paṭihaññati—“to be resentful”: not in PED; the verb has been needed to correspond to “resentment” (paṭigha), as the verb, “to be inflamed with greed” (rajjati) corresponds with “greed” (rāga).

[6]:

Sambhāvetvā—“judging”: not in this sense in PED. Vism-mhṭ (p. 313) explains by parikappetvā (conjecturing).

[7]:

For which kinds of body contemplation give which kinds of concentration see 8.43 and M-a I 247.

[8]:

“‘Mere unification of the mind’: the kind of concentrating (samādhāna) that is undeveloped and just obtained by one in pursuit of development. That is called ‘basic concentration,’ however, since it is the basic reason for the kinds of more distinguished concentration to be mentioned later in this connection. This ‘mere unification of the mind’ is intended as momentary concentration as in the passage beginning, ‘I internally settled, steadied, unified and concentrated my mind’ (M I 116). For the first unification of the mind is recognized as momentary concentration here as it is in the first of the two successive descriptions: ‘Tireless energy was aroused in me … my mind was concentrated and unified’ followed by ‘Quite secluded from sense desires …’” (M I 21) (Vism-mhṭ 314).

[9]:

“‘Thus developed’: just as a fire started with wood and banked up with cowdung, dust, etc., although it arrives at the state of a ‘cowdung fire,’ etc., (cf. M I 259) is nevertheless called after the original fire that was started with the wood, so too it is the basic concentration that is spoken of here, taking it as banked up with lovingkindness, and so on. ‘In other objects’ means in such objects as the earth kasiṇa” (Vism-mhṭ 315).

[10]:

“The beautiful” (subha) is the third of the eight liberations (vimokkha—see M II 12; M-a III 255).

[11]:

Reading in both cases “avijjamāna-gahaṇa-dakkhaṃ cittaṃ,” not “-dukkhaṃ.” “‘Because it has no more concern (ābhoga)’: because it has no further act of being concerned (ābhujana) by hoping (āsiṃsanā) for their pleasure, etc., thus ‘May they be happy.’ The development of loving-kindness, etc., occurring as it does in the form of hope for beings’ pleasure, etc., makes them its object by directing [the mind] to apprehension of [what is existent in] the ultimate sense [i.e. pleasure, etc.]. But development of equanimity, instead of occurring like that, makes beings its object by simply looking on. But does not the divine abiding of equanimity itself too make beings its object by directing the mind to apprehension of [what is existent in] the ultimate sense, because of the words, ‘Beings are owners of their deeds. Whose [if not theirs] is the choice by which they will become happy …?’ (§96)—Certainly that is so. But that is in the prior stage of development of equanimity. When it has reached its culmination, it makes beings its object by simply looking on. So its occurrence is specially occupied with what is non-existent in the ultimate sense [i.e. beings, which are a concept]. And so skill in apprehending the non-existent should be understood as avoidance of bewilderment due to misrepresentation in apprehension of beings, which avoidance of bewilderment has reached absorption” (Vism-mhṭ).

[12]:

For the “ten powers” and “four kinds of fearlessness” see MN 12. For the “six kinds of knowledge not shared by disciples” see Paṭis I 121f. For the “eighteen states of the Enlightened One” see Cp-a.