Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Many Youths which is verse 131-132 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 131-132 is part of the Daṇḍa Vagga (Punishment) and the moral of the story is “Harassing others in quest of one’s own happiness, one gains not happiness hereafter” (first part only).

Verse 131-132 - The Story of Many Youths

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 131-132:

sukhakāmāni bhūtāni yo daṇḍena vihiṃsati |

attano sukhamesāno pecca so na labhate sukhaṃ || 131 ||

sukhakāmāni bhūtāni yo daṇḍena na hiṃsati |

attano sukhamesāno pecca so labhate sukhaṃ || 132 ||

131. Whoever harms with force those desiring happiness, as seeker after happiness one gains no future joy.

132. Whoever doesn’t harm with force those desiring happiness, as seeker after happiness one then gains future joy.

Harassing others in quest of one’s own happiness, one gains not happiness hereafter. |

Harassing not others, those who seek happiness gain their own happiness hereafter. |

The Story of Many Youths

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke these verses, with reference to a number of youths.

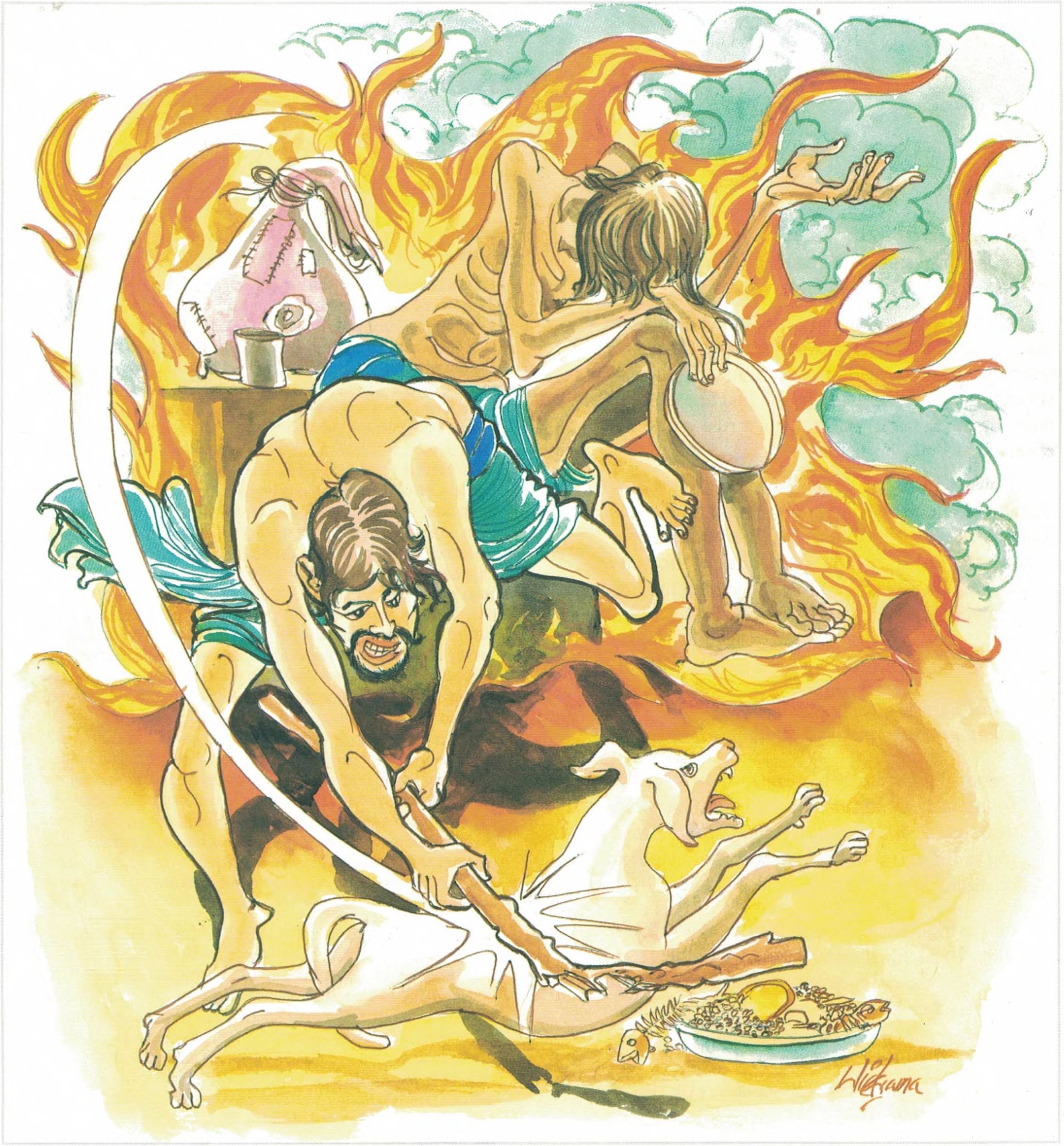

Once, the Buddha was out on an alms-round at Sāvatthi when he came across a number of youths beating a snake with sticks. When questioned, the youths answered that they were beating the snake because they were afraid that the snake might bite them. To them the Buddha said, “If you do not want to be harmed, you should also not harm others: if you harm others, you will not find happiness in your next existence.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 131)

yo attano sukhaṃ esāno sukha kāmāni bhūtāni

daṇḍena vihiṃsati so pecca sukhaṃ na labhate

yo: if someone; attano [attana]: one’s own; sukhaṃ esāno [esāna]: seeking happiness; yo: if someone; sukha kāmāni bhūtāni: equally happiness-seeking beings; daṇḍena: with rods (with various inflictions); vihiṃsati: tortures (gives pain to); so: that person; pecca: in the next birth too; sukhaṃ [sukha]: happiness; na labhate: does not achieve (happiness)

People who like to be happy and are in search of pleasure hurt others through various acts of violence for their own happiness. These victims too want to be happy as much as those who inflict pain on them. Those who inflict pain do not achieve happiness even in their next birth.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 132)

yo attano sukhaṃ esāno sukha kāmāni bhūtāni

daṇḍena na hiṃsati, so pecca sukhaṃ labhate

yo: if someone; attano [attana]: one’s own; sukhaṃ esāno [esāna]: seeking happiness; sukha kāmāni: equally happiness-seeking; bhūtāni: beings; daṇḍena: with rods (with various inflictions); na hiṃsati: does not hurt, torture or give pain; so: that person; pecca: in the next world; sukhaṃ [sukha]: happiness; labhate: achieves

If people who like happiness for themselves and are in search of pleasure for themselves, do not hurt or torture others or give pain to others, they achieve happiness in the next life too.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 131-132)

Anāthapiṇḍika and Jetavana: most of the stanzas in Dhammapada were spoken by the Buddha while residing at Jetavanārāma, built by Anāthapiṇḍika. In consequence, both these are important institutions for Buddhist especially to Dhammapada. The original name of Anāthapiṇḍika, which means the feeder of the helpless, was Sudatta. Owing to his unparalleled generosity he was latterly known by his new name. His birthplace was Sāvatthi. One day he visited his brother-inlaw in Rājagaha to transact some business. He did not come forward as usual to welcome him but Sudatta found him in the garden making preparations for a feast. On inquiry, to his indescribable joy, he understood that those arrangements were being made to entertain the Buddha on the following day. The utterance of the mere word Buddha roused his interest and he longed to see Him. As he was told that the Buddha was living in the Sītavana forest in the neighbourhood and that he could see Him on the following morning, he went to sleep. His desire to visit the Buddha was so intense that he had a sleepless night and he arose at an unusual hour in the morning to start for the Sītavana. It appears that, owing to his great faith in the Buddha, a light emanated from his body. He proceeded to the spot passing through a cemetery. It was pitch dark and a fear arose in him. He thought of turning back.

Then Sīvaka, a yakkha, himself invisible, encouraged him, saying:

A hundred elephants and horses too,

Ay, and a hundred chariots drawn by mules,

A hundred thousand maidens, in their ears

Bejewelled rings:–all are not worth

The sixteenth fraction of a single stride.

Advance, O citizen, go forward thou!

Advance for thee is better than retreat.

His fear vanished and faith in the Buddha arose in its place. Light appeared again, and he courageously sped forward. Nevertheless, all this happened a second time and yet a third time. Ultimately he reached Sītavana where the Buddha was pacing up and down in the open air anticipating his visit. The Buddha addressed him by his family name, Sudatta, and called him to His presence. Anāthapiṇḍika was pleased to hear the Buddha address him thus and respectfully inquired whether the Buddha rested happily.

The Buddha replied:

Sure at all times happily doth rest

The arahat in whom all fire’s extinct.

Who cleaveth not to sensuous desires,

Cool all his being, rid of all the germs

That bring new life, all cumbrances cut out,

Subdued the pain and pining of the heart,

Calm and serene he resteth happily

For in his mind he hath attained to Peace.

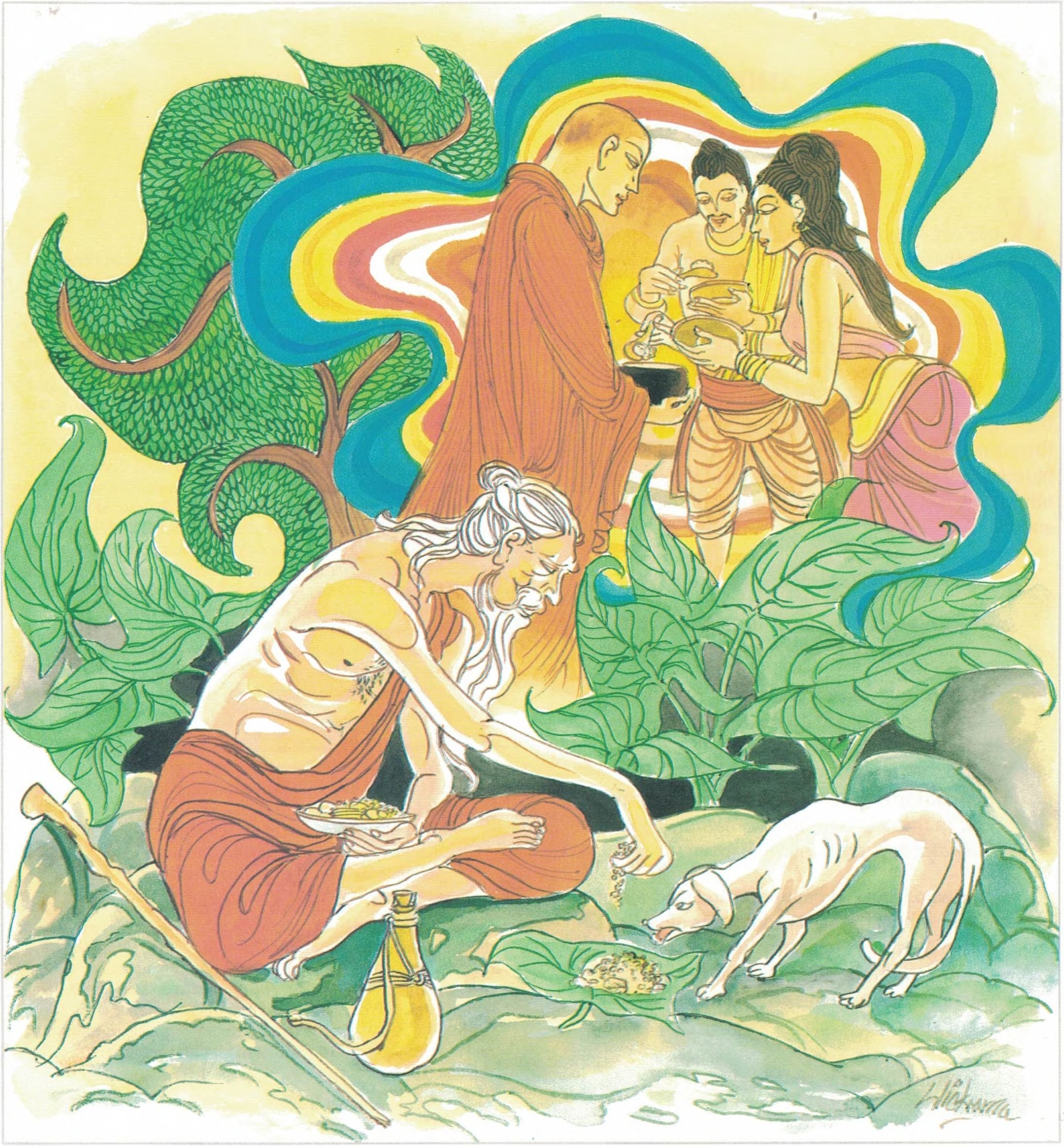

Hearing the Dhamma, he became a sotāpanna (stream-winner), and invited the Buddha to spend the rainy season at Sāvatthi. The Buddha accepted the invitation suggesting that Buddhas take pleasure in solitude. Anāthapiṇḍika, returning to Sāvatthi, bought the park belonging to Prince Jeta at a price determined by covering, so the story goes, the whole site with gold coins, and erected the famous Jetavana Monastery at a great cost. Here the Buddha spent nineteen rainy seasons. This monastery where the Buddha spent the major part of His life was the place where He delivered many of His sermons. Several discourses, which were of particular interest to laymen, were delivered to Anāthapiṇḍika, although he refrained from asking any question from the Buddha, lest he should weary Him.

Once, the Buddha, discoursing on generosity, reminded Anāthapiṇḍika that alms given to the Sangha together with the Buddha is very meritorious; but more meritorious than such alms is the building of a monastery for the use of the Sangha; more meritorious than such monasteries is seeking refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha; more meritorious than seeking refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Sangha, is the observance of the five precepts; more meritorious than such observance is meditation on loving-kindness (mettā) for a moment; and most meritorious of all is the development of Insight as to the fleeting nature of things (passanā).

On another occasion when the Buddha visited the house of Anāthapiṇḍika, he heard an unusual uproar inside the house and inquired what it was. “Lord, it is Sujātā, my daughter-in-law, who lives with us. She is rich and has been brought here from a wealthy family. She pays no heed to her mother-in-law, nor to her father-in-law, nor to her husband; neither does she venerate, honour, reverence nor respect the Buddha,” replied Anāthapiṇḍika.

The Buddha called her to His presence and preached an illuminative discourse on seven kinds of wives that exist even in modern society as it was in the days of old.

Who so is wicked in mind, ill-disposed, pitiless, fond of other (men) neglecting husband, a prostitute, bent on harassing–such a one is called a troublesome wife. (vadhakabhariyā)

Who so wishes to squander whatever profits, though little, that the husband gains whether by crafts, trade, or plough–such a one is called a thievish wife. (corabhariyā)

Who so is not inclined to do anything, lazy, gluttonous, harsh, cruel, fond of bad speech, lives domineering the industrious–such a one is called a lordly wife. (ayyabhariyā)

Who so is ever kind and compassionate, protects her husband like a mother, her son, guards the accumulated wealth of her husband–such a one is called a motherly wife. (mātubhariyā)

Who so is respectful towards her husband just as a younger sister towards her elder brother, modest, lives in accordance with her husband’s wishes–such a one is called a sisterly wife. (bhaginibhariyā)

Who so rejoices at the sight of her husband even as a friend on seeing a companion who has come after a long time, is of noble birth, virtuous and chaste–such a one is called a friendly wife. (sakhibhariyā)

Who so, when threatened with harm and punishment, is not angry but calm, endures all things of her husband with no wicked heart, free from hatred, lives in accordance with her husband’s wishes–such a one is called a handmaid wife. (dāsibhariyā)

The Buddha describing the characteristics of the seven kinds of wives remarked that of them the troublesome wife (vadhakabhariyā), the thievish wife (corabhariyā), and the lordly wife (ayyabhariyā), are bad and undesirable ones, while the motherly wife (mātubhariyā), sisterly wife (bhaginibhariyā), friendly wife (sakhibhariyā), and handmaid wife (dāsibhariyā), are good and praiseworthy ones.

“These Sujātā, are the seven kinds of wives a man may have: and which of them are you?” “Lord, let the Buddha think of me as a handmaid wife (dāsibhariyā) from this day forth.”

Anāthapiṇḍika used to visit the Buddha daily and, finding that people go disappointed in the absence of the Buddha, wished to know from the Venerable Ānanda whether there was a possibility for the devout followers to pay their respects when the Buddha went out on His preaching tours. This matter was reported to the Buddha with the result that the Ānanda-Bodhi tree, which stands to this day, was planted at the entrance to the monastery.

sukhaṃ: happiness. Commenting on the four kinds of happiness a layman may enjoy, the Buddha declared: “There are these four kinds of happiness to be won by the householder who enjoys the pleasures of sense, from time to time and when occasion offers. They are: the happiness of ownership (atthisukha), the happiness of enjoyment (bhogasukha), the happiness of debtlessness (ananasukha), and the happiness of innocence (anavajjasukha).

“What is the happiness of ownership?” Herein a clansman has wealth acquired by energetic striving, amassed by strength of arm, won by sweat, lawful, and lawfully gotten. At the thought, wealth is mine, acquired by energetic striving, lawfully gotten, happiness comes to him, satisfaction comes to him. This is called the happiness of ownership.

“What is the happiness of debtlessness?” Herein a clansman owes no debt, great or small, to anyone. At the thought, I owe no debt, great or small, to anyone, happiness comes to him, satisfaction comes to him. This is called the happiness of debtlessness.

“What is the happiness of innocence? Herein the Aryan disciple is blessed with blameless action of body, blameless action of speech, blameless action of mind. At the thought, I am blessed with blameless action of body, speech and mind, happiness comes to him, satisfaction comes to him. This is called the happiness of innocence.”

Winning the bliss of debtlessness a man

May then recall the bliss of really having.

When he enjoys the bliss of wealth, he sees

’Tis such by wisdom. When he sees he knows.

Thus is he wise indeed in both respects.

But these have not one-sixteenth of the bliss

(That cometh to a man) of blamelessness.