Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

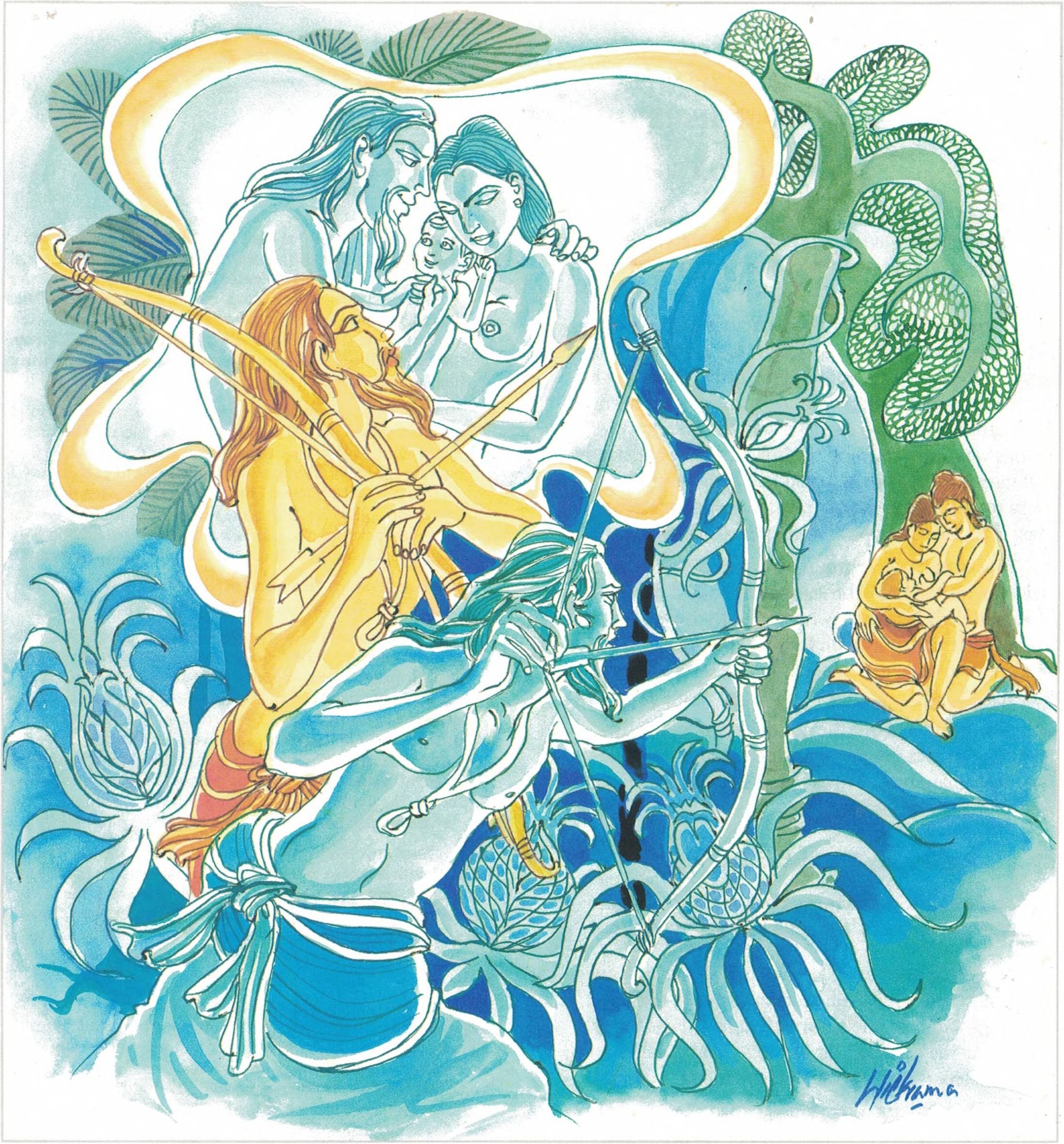

This page describes The Story of a Group of Six Monks (continued) which is verse 130 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 130 is part of the Daṇḍa Vagga (Punishment) and the moral of the story is “Life is dear to all. Taking oneself as the example, kill not, hurt not”.

Verse 130 - The Story of a Group of Six Monks (continued)

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 130:

sabbe tasanti daṇaḍassa sabbesaṃ jīvitaṃ piyaṃ |

attānaṃ upamaṃ katvā na haneyya na ghātaye || 130 ||

130. All tremble at force, dear is life to all. Likening others to oneself kill not nor cause to kill.

Life is dear to all. Taking oneself as the example, kill not, hurt not. |

The Story of a Group of Six Monks

While residing at the Jetavana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to a group of six monks. This is linked to the previous verse.

After having exchanged blows over the incident at the Jetavana Monastery, the same two groups of monks quarrelled again over the same building. As the rule relating to physically hurting others had already been laid down by the Buddha, this particular rule was strictly observed by both groups.

However, this time one of the two groups made threatening gestures to the other group, to the extent that the latter cried out in fright. The Buddha, after hearing about this threatening attitude of the monks, introduced the disciplinary rule preventing the making of threatening gestures to each other.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 130)

sabbe daṇḍassa tasanti sabbesaṃ jīvitaṃ piyaṃ

attānaṃ upamaṃ katvā na haneyya na ghātaye

sabbe: all; daṇḍassa: at punishment; tasanti: are frightened; sabbesaṃ [sabbesa]: to all; jīvitaṃ [jīvita]: life; piyaṃ [piya]: dear; attānaṃ [attāna]: one’s own self; upamaṃ katvā: taking as the example; na haneyya: do not kill; na ghātaye: do not get anyone else to kill

All are frightened of being hurt or of any threat to one’s life. To all, life is dear. Seeing that others feel the same way as oneself, equating others to oneself, refrain from harming or killing.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 130)

na haneyya, na ghātaye: do not destroy; do not kill. Here, the quality that is being inculcated is compassion. Disagreements and disputes arise due to lack of compassion. A universal compassion arises only when there is the perception of true reality. Compassion expresses itself through wholesome action. Compassion is not merely thinking compassionate thoughts. It has to show itself through compassionate action. Compassion is taking note of the sufferings of other beings in the world. It overcomes callous indifference to the plight of suffering beings, human or otherwise. Likewise, it must be reflected in one’s life by a willingness to go out of one’s way to give aid where possible and to help those in distress. It has the advantage of reducing one’s selfishness by understanding others’ sorrows. It is Lord Buddha’s medicine for cruelty, for how can one harm others when one has seen how much they have to suffer already? It has also two enemies: the ‘near’ one is mere grief, while its ‘far’ enemy is cruelty.

Mettā: compassion–loving-kindness. Mettā is the first of the four sublime states. It means that which softens one’s heart, or the state of a true friend. It is defined as the sincere wish for the welfare and genuine happiness of all living beings without exception. It is also explained as the friendly disposition, for a genuine friend sincerely wishes for the welfare of his friend.

“Just as a mother protects her only child even at the risk of her life, even so one should cultivate boundless loving-kindness towards all living beings” is the advice of the Buddha. It is not the passionate love of the mother towards her child that is stressed here but her sincere wish for the genuine welfare of her child. Mettā is neither carnal love nor personal affection, for grief inevitably arises from both. Mettā is not mere neighbourliness, for it makes no distinction between neighbours and others. Mettā is not mere universal brotherhood, for it embraces all living beings including animals, our lesser brethren and sisters that need greater compassion as they are helpless. Mettā is not religious brotherhood either. Owing to the sad limitations of so-called religious brotherhood human heads have been severed without the least compunction, sincere outspoken men and women have been roasted and burnt alive; many atrocities have been perpetrated which baffle description; cruel wars have been waged which mar the pages of world history. Even in this supposedly enlightened twentieth century the followers of one religion hate or ruthlessly persecute and even kill those of other faiths merely because they cannot force them to think as they do or because they have a different label. If, on account of religious views, people of different faiths cannot meet on a common platform like brothers and sisters, then surely the missions of compassionate world teachers have pitifully failed. Sweet mettā transcends all these kinds of narrow brotherhood. It is limitless in scope and range. Barriers it has none. Discrimination it makes not. Mettā enables one to regard the whole world as one’s motherland and all as fellow-beings. Just as the sun sheds its rays on all without any distinction, even so sublime mettā bestows its sweet blessings equally on the pleasant and the unpleasant, on the rich and the poor, on the high and the low, on the vicious and the virtuous, on man and woman, and on human and animal.

Such was the boundless mettā of the Buddha who worked for the welfare and happiness of those who loved Him as well as of those who hated Him and even attempted to harm and kill Him. The Buddha exercised mettā equally towards His own son Rāhula, His adversary Devadatta, His attendant Ānanda, His admirers and His opponents. This loving-kindness should be extended in equal measure towards oneself as towards friend, foe and neutral alike. Suppose a bandit were to approach a person travelling through a forest with an intimate friend, a neutral person and an enemy, and suppose he were to demand that one of them be offered as a victim. If the traveller were to say that he himself should be taken, then he would have no mettā towards himself. If he were to say that anyone of the other three persons should be taken, then he would have no mettā towards them.

Such is the characteristic of real mettā. In exercising this boundless loving-kindness oneself should not be ignored. This subtle point should not be misunderstood, for self-sacrifice is another sweet virtue and egolessness is yet another higher virtue. The culmination of this mettā is the identification of oneself with all beings (sabbattatā), making no difference between oneself and others. The so-called I is lost in the whole. Separatism evaporates. Oneness is realized.

There is no proper English equivalent for this graceful Pāli term mettā. Goodwill, loving-kindness, benevolence and universal love are suggested as the best renderings. The antithesis of mettā is anger, illwill, hatred, or aversion. Mettā cannot co-exist with anger or vengeful conduct.