Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

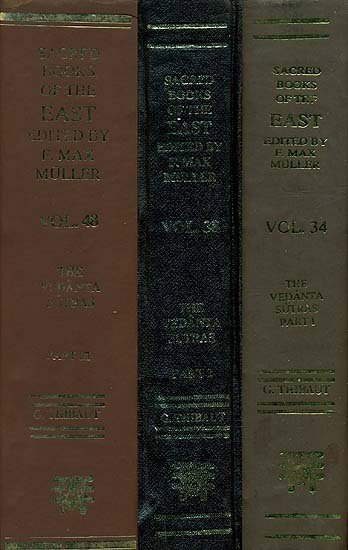

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 3.3.7

7. Or not, on account of difference of subject-matter; as in the case of the attribute of being higher than the high, and so on.

There is no unity of the two vidyās, since the subject-matter of the two differs. For the tale in the Chāndogya-text, which begins 'when the Devas and the Asuras struggled together,' connects itself with the praṇava (the syllable Om) which is introduced as the object of meditation in Chánd. I, 1, 1, 'Let a man meditate on the syllable Om as the Udgītha'; and the clause forming part of the tale,'they meditated on that chief breath as Udgītha.' therefore refers to a meditation on the praṇava which is a part only of the Udgītha. In the text of the Vāja-saneyins; on the other hand, there is nothing to correspond to the introductory passage which in the Chāndogya-text determines the subject-matter, and the text clearly states that the meditation refers to the whole Udgītha (not only the praṇava). And this difference of leading subject-matter implies difference of matter enjoined, and this again difference of the character of meditation, and hence there is no unity of vidyās. Thus the object of meditation for the Chandogas is the praṇava viewed under the form of Prāṇa; while for the Vājasaneyins it is the Udgātri (who sings the Udgītha), imaginatively identified with Prāṇa. Nor does there arise, on this latter account, a contradiction between the later and the earlier part of the story of the Vājasaneyins. For as a meditation on the Udgātṛ necessarily extends to the Udgītha, which is the object of the activity of singing, the latter also helps to bring about the result, viz. the mastering of enemies.—There is thus no unity of vidyā, although there may be non-difference of injunction, and so on.—'As in the case of the attribute of being higher than the high,' etc. In one and the same śākhā there are two meditations, in each of which the highest Self is enjoined to be viewed under the form of the praṇava (Ch. Up. I, 6; I, 9), and in so far the two vidyās are alike. But while the former text enjoins that the praṇava has to be viewed under the form of a golden man, in the latter he has to be viewed as possessing the attributes of being higher than the high, and owing to this difference of attributes the two meditations must be held separate (a fortiori, then, those meditations are separate which have different objects of meditation).