Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

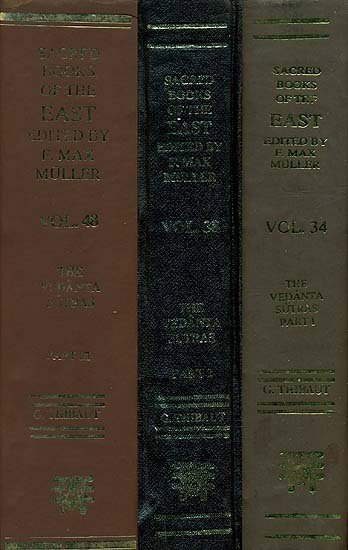

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 2.1.9

9. Not so; as there are parallel instances.

The teaching of the Vedānta-texts is not inappropriate, since there are instances of good and bad qualities being separate in the case of one thing connected with two different states. The 'but' in the Sūtra indicates the impossibility of Brahman being connected with even a shadow of what is evil. The meaning is as follows. As Brahman has all sentient and non-sentient things for its body, and constitutes the Self of that body, there is nothing contrary to reason in Brahman being connected with two states, a causal and an effected one, the essential characteristics of which are expansion on the one hand and contraction on the other; for this expansion and contraction belong (not to Brahman itself, but) to the sentient and non-sentient beings. The imperfections adhering to the body do not affect Brahman, and the good qualities belonging to the Self do not extend to the body; in the same way as youth, childhood, and old age, which are attributes of embodied beings, such as gods or men, belong to the body only, not to the embodied Self; while knowledge, pleasure and so on belong to the conscious Self only, not to the body. On this understanding there is no objection to expressions such as 'he is born as a god or as a man' and 'the same person is a child, and then a youth, and then an old man' That the character of a god or man belongs to the individual soul only in so far as it has a body, will be shown under III, 1, 1.

The assertion made by the Pūrvapakshin as to the impossibility of the world, comprising matter and souls and being either in its subtle or its gross condition, standing to Brahman in the relation of a body, we declare to be the vain outcome of altogether vicious reasoning springing from the idle fancies of persons who have never fully considered the meaning of the whole body of Vedānta-texts as supported by legitimate argumentation. For as a matter of fact all Vedānta-texts distinctly declare that the entire world, subtle or gross, material or spiritual, stands to the highest Self in the relation of a body. Compare e.g.the antaryāmin-brāhmaṇa, in the Kāṇva as well as the Mādhyandina-text, where it is said first of non-sentient things ('he who dwells within the earth, whose body the earth is' etc.), and afterwards separately of the intelligent soul ('he who dwells in understanding,' according to the Kāṇvas; 'he who dwells within the Self,' according to the Mādhyandinas) that they constitute the body of the highest Self. Similarly the Subāla-Upanishad declares that matter and souls in all their states constitute the body of the highest Self ('He who dwells within the earth' etc.), and concludes by saying that that Self is the soul of all those beings ('He is the inner Self of all' etc.). Similarly Smṛti, 'The whole world is thy body'; 'Water is the body of Vishṇu'; 'All this is the body of Hari'; 'All these things are his body'; 'He having reflected sent forth from his body'—where the 'body' means the elements in their subtle state. In ordinary language the word 'body' is not, like words such as jar , limited in its denotation to things of one definite make or character, but is observed to be applied directly (not only secondarily or metaphorically) to things of altogether different make and characteristics—such as worms, insects, moths, snakes, men, four-footed animals, and so on. We must therefore aim at giving a definition of the word that is in agreement with general use. The definitions given by the Pūrvapakshin—'a body is that which causes the enjoyment of the fruit of actions' etc.—do not fulfil this requirement; for they do not take in such things as earth and the like which the texts declare to be the body of the Lord. And further they do not take in those bodily forms which the Lord assumes according to his wish, nor the bodily forms released souls may assume, according to 'He is one' etc. (Ch. Up. VII, 36, 2); for none of those embodiments subserve the fruition of the results of actions. And further, the bodily forms which the Supreme Person assumes at wish are not special combinations of earth and the other elements; for Smṛti says, 'The body of that highest Self is not made from a combination of the elements.' It thus appears that it is also too narrow a definition to say that a body is a combination of the different elements. Again, to say that a body is that, the life of which depends on the vital breath with its five modifications is also too narrow, viz in respect of plants; for although vital air is present in plants, it does not in them support the body by appearing in five special forms. Nor again does it answer to define a body as either the abode of the sense-organs or as the cause of pleasure and pain; for neither of these definitions takes in the bodies of stone or wood which were bestowed on Ahalyā and other persons in accordance with their deeds. We are thus led to adopt the following definition—Any substance which a sentient soul is capable of completely controlling and supporting for its own purposes, and which stands to the soul in an entirely subordinate relation, is the body of that soul. In the case of bodies injured, paralysed, etc., control and so on are not actually perceived because the power of control, although existing, is obstructed; in the same way as, owing to some obstruction, the powers of fire, heat,and so on may not be actually perceived. A dead body again begins to decay at the very moment in which the soul departs from it, and is actually dissolved shortly after; it (thus strictly speaking is not a body at all but) is spoken of as a body because it is a part of the aggregate of matter which previously constituted a body. In this sense, then, all sentient and non-sentient beings together constitute the body of the Supreme Person, for they are completely controlled and supported by him for his own ends, and are absolutely subordinate to him. Texts which speak of the highest Self as 'bodiless among bodies' (e.g. Ka. Up. I. 2, 22), only mean to deny of the Self a body due to karman; for as we have seen, Scripture declares that the Universe is his body. This point will be fully established in subsequent adhikaraṇas also. The two preceding Sūtras (8 and 9) merely suggest the matter proved in the adhikaraṇa beginning with II, 1, 21.