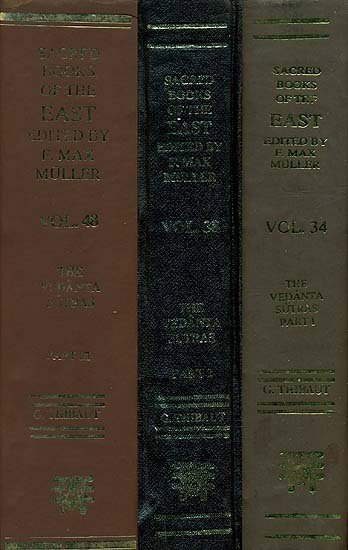

Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 3.3.1

1. What is understood from all the Vedānta-texts (is one), on account of the non-difference of injunction and the rest.

The Sūtras have stated whatever has to be stated to the end of rousing the desire of meditation-concluding with the fact that Brahman bestows rewards. Next the question is introduced whether the vidyās (i.e. the different forms of meditation on Brahman which the Vedānta-texts enjoin) are different or non-different, on the decision of which question it will depend whether the qualities attributed to Brahman in those vidyās are to be comprised in one act of meditation or not.—The first subordinate question arising here is whether one and the same meditation—as e.g. the vidyā of Vaiśvānara—which is met with in the text of several śākhās, constitutes one vidyā or several.—The vidyās are separate, the Pūrvapakshin maintains; for the fact that the same matter is, without difference, imparted for a second time, and moreover stands under a different heading—both which circumstances necessarily attend the text’s being met with in different śākhās—proves the difference of the two meditations. It is for this reason only that a restrictive injunction, such as the one conveyed in the text, 'Let a man tell this science of Brahman to those only who have performed the rite of carrying fire on their head' (Mu. Up. III, 2, 10)—which restricts the impaiting of knowledge to the Ātharvaṇikas, to whom that rite is peculiar—has any sense; for if the vidyās were one, then the rite mentioned, which is a part of the vidyā, would be valid for the members of other śākhās also, and then the restriction enjoined by the text would have no meaning.—This view is set aside by the Sūtra, 'What is understood from all the Vedānta-texts' is one and the same meditation, 'because there is non-difference of injunction and the rest.' By injunction is meant the injunction of special activities denoted by different verbal roots—such as upāsīta 'he should meditate,' vidyāt 'he should know.' The and the rest' of the Sūtra is meant to comprise as additional reasons the circumstances mentioned in the Pūrva Mīmāṃsā-sūtras (II, 4, 9). Owing to all these circumstances, non-difference of injunction and the rest, the same vidyā is recognised in other śākhās also. In the Chāandogya (V, 12, 2) as well as in the Vājasaneyaka we meet with one and the same injunction (viz. 'He should meditate on Vaiśvānara'). The form (character, rūpa) of the meditations also is the same, for the form of a cognition solely depends on its object; and the object is in both cases the same, viz. Vaiśvānara. The name of the two vidyās also is the same, viz. the knowledge of Vaiśvānara. And both vidyās are declared to have the same result, viz. attaining to Brahman. All these reasons establish the identity of vidyās even in different śākhās.—The next Sūtra refers to the reasons set forth for his view by the Pūrvapakshin and refutes them.