Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Sariputta being misunderstood which is verse 410 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 410 is part of the Brāhmaṇa Vagga (The Brāhmaṇa) and the moral of the story is “Not yearning for this world or the next, and liberated and longingless. Him I call a brahmin true”.

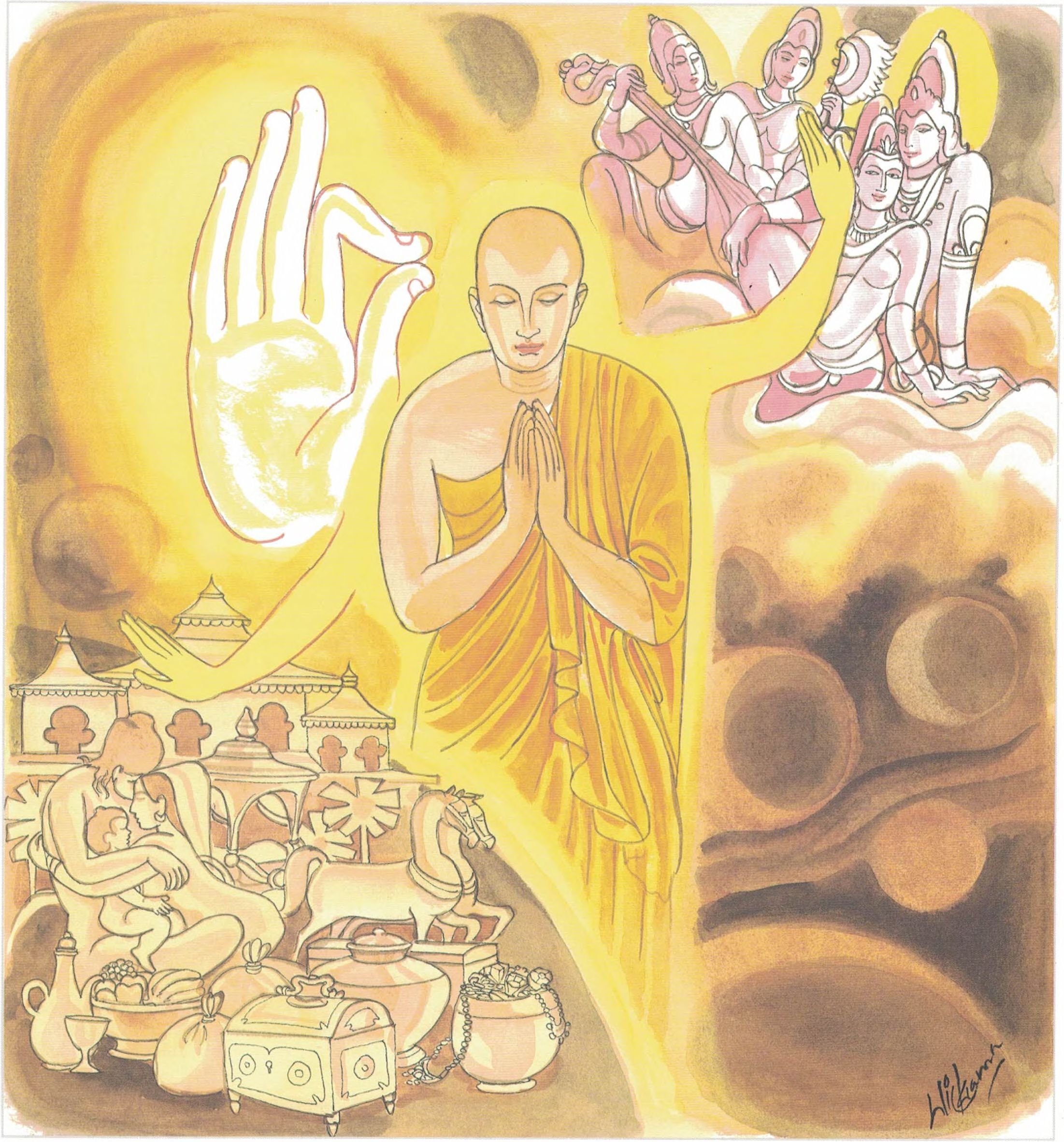

Verse 410 - The Story of Sāriputta being misunderstood

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 410:

āsā yassa na vijjanti asmiṃ loke paramhi ca |

nirāsayaṃ visaṃyuttaṃ tamahaṃ brūmi brāhmaṇaṃ || 410 ||

410. In whom there are no longings found in this world or the next, longingless and free from bonds, that one I call a Brahmin True.

Not yearning for this world or the next, and liberated and longingless. Him I call a brahmin true. |

The Story of Sāriputta being misunderstood

The story goes that once upon a time Venerable Sāriputta, accompanied by his retinue of five hundred monks, went to a certain monastery and entered upon residence for the season of the rains. When the people saw the Venerable, they promised to provide him with all of the requisites for residence. But even after the Venerable had celebrated the terminal festival, not all of the requisites had as yet arrived. So when he set out to go to the Buddha he said to the monks, “When the people bring the requisites for the young monks and novices, pray take them and send them on; should they not bring them, be good enough to send me word.” So saying, he went to the Buddha.

The monks immediately began to discuss the matter, saying, “Judging by what Venerable Sāriputta said to-day, Craving still persists within him. For when he went back, he said to the monks with reference to the requisites for residence given to his own fellow residents, ‘Pray send them on; otherwise be good enough to send me word.’” Just then the Buddha drew near. “Monks,” said he, “what is the subject that engages your attention now as you sit here all gathered together?” “Such and such,” was the reply. The Buddha said, “No, monks, my son has no craving. But the following thought was present to his mind, ‘May there be no loss of merit to the people, and no loss of holy gain to the young monks and novices.’ This is the reason why he spoke as he did.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 410)

yassa asmiṃ loke paraṃhi ca āsā na vijjanti

nirāsayaṃ visaṃyuttaṃ taṃ ahaṃ brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi

yassa: if someone; asmiṃ loke: in this world; paraṃhica: or in the next; āsā: cravings; na vijjanti: does not possess; nirāsayaṃ [nirāsaya]: that cravingless; visaṃ yuttaṃ [yutta]: disengaged from defilements; taṃ: person; ahaṃ: I; brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi: declare a brāhmaṇa

He has no yearnings either for this world or for the next. He is free from yearning and greed. He is disengaged from defilements. Such a person I declare a fine brāhmaṇa.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 410)

āsā: It is this thirst (craving, taṇhā) which produces re-existence and re-becoming (ponobhavikā), and which is bound up with passionate greed (nandīrāgasahagatā), and which finds fresh delight now here and now there (tatratatrābhinandinī), such as (i) thirst for sense-pleasures (kāma-taṇhā), (ii) thirst for existence and becoming (bhavataṇhā) and (iii) thirst for non-existence (self-annihilation, vibhavataṇhā).

It is this thirst, desire, greed, craving, manifesting itself in various ways, that gives rise to all forms of suffering and the continuity of beings. But it should not be taken as the first cause, for there is no first cause possible as, according to Buddhism, everything is relative and inter-dependent. Even this thirst, taṇhā, which is considered as the cause or origin of dukkha, depends for its arising (samudaya) on something else, which is sensation (vedanā), and sensation arises depending on contact (phassa), and so on and so forth, goes on the circle which is known as conditioned genesis (paṭicca-samuppāda), which we will discuss later.

So taṇhā, thirst, is not the first or the only cause of the arising of dukkha. But it is the most palpable and immediate cause, the principal thing and the all-pervading thing. Hence, in certain places of the original Pāli texts the definition of samudaya or the origin of dukkha includes other defilements and impurities (kilesā, sāsavā dhammā), in addition to taṇhā, thirst, which is always given the first place. Within the necessarily limited space of our discussion, it will be sufficient if we remember that this thirst has, as its centre, the false idea of self arising out of ignorance.

Here the term thirst includes not only desire for, and attachment to, sense-pleasures, wealth and power, but also desire for, and attachment to, ideas and ideals, views, opinions, theories, conceptions and beliefs (dhamma-taṇhā). According to the Buddha’s analysis, all the troubles and strife in the world, from little personal quarrels in families to great wars between nations and countries, arise out of this selfish thirst. From this point of view, all economic, political and social problems are rooted in this selfish thirst. Great statesmen who try to settle international disputes and talk of war and peace only in economic and political terms touch the superficialities, and never go deep into the real root of the problem. As the Buddha told Raṭṭhapāla: The world lacks and hankers, and is enslaved to thirst (taṇhādāso).