Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Venerable Maha Panthaka which is verse 407 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 407 is part of the Brāhmaṇa Vagga (The Brāhmaṇa) and the moral of the story is “Lust, hate and pride totally felled, like a mustard off a needle. Him I call a brahmin true”.

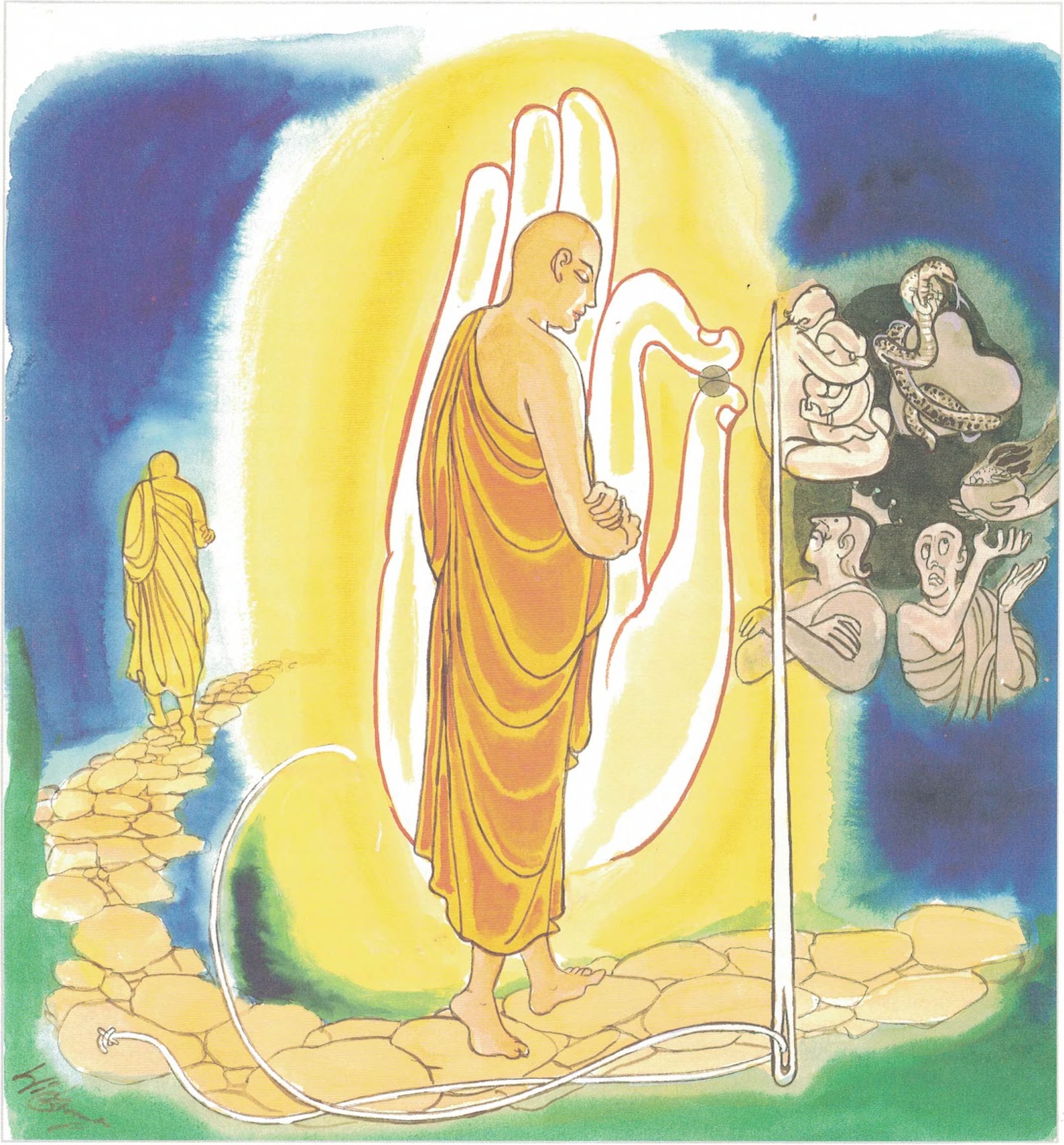

Verse 407 - The Story of Venerable Mahā Panthaka

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 407:

yassa rāgo ca doso ca māno makkho ca pātito |

sāsapor'iva āraggā tam ahaṃ brūmi brāhmaṇaṃ || 407 ||

407. From whomever lust and hate, conceit, contempt have dropped away, as mustard seed from a needle point, that one I call a Brahmin True.

Lust, hate and pride totally felled, like a mustard off a needle. Him I call a brahmin true. |

The Story of Venerable Mahā Panthaka

This verse was spoken by the Buddha while He was in residence at Veluvana Monastery, with reference to Venerable Mahā Panthaka.

When Culla Panthaka was unable to learn by heart a single stanza in three months, Mahā Panthaka expelled him from the monastery and closed the door, saying to him, “You lack the capacity to receive religious instruction, and you have also fallen away from the enjoyments of the life of a householder. Why should you continue to live here any longer? Depart hence.” The monks began a discussion of the incident, saying, “Venerable Mahā Panthaka did this and that. Doubtless anger springs up sometimes even within those who have rid themselves of the Depravities.” At that moment the Buddha drew near and asked them, “Monks, what is the subject that engages your attention now as you sit here all gathered together?” When the monks told him the subject of their conversation, he said, “No, monks, those who have rid themselves of the depravities have not the contaminations, lust, hatred, and delusion. What my son did he did because he put the Dhamma, and the spirit of the Dhamma, before all things else.”

Explanatory Translation (Verse 407)

yassa rāgo ca doso ca māno makkho ca āraggā

sāsapor’iva pātito taṃ ahaṃ brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi

yassa: by some one; rāgo ca: lust; doso ca: ill-will; māno [ māna]: pride; makkho ca: (and) ingratitude; āraggā: from the point of a needle; sāsapo iva: like a seed of mustard; pātito [pātita]: slipped; taṃ: him; ahaṃ: I; brāhmaṇaṃ brūmi: declare a brāhmaṇa

His mind just does not accept such evils as lust, ill-will, pride and ingratitude. In this, his mind is like the point of a needle that just does not grasp a mustard seed. An individual endowed with such a mind I describe as a brāhmaṇa.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 407)

The story of the two brother monks: Mahā Panthaka (Big Road) and Culla Panthaka (Small Road). Cullapanthaka was associated with his elder brother who is called Mahā Panthaka. As both were born on the road they were called Panthaka. Culla Panthaka was distinguished from all the mahā arahats by the power to form any number of corporeal figures by psychic power and also by his ability to practice mystic meditation in the world of form.

They were the offspring of a daughter of a treasurer entering into a clandestine marriage with a servant of her father’s household. This explains the birth of the first child while the expectant mother was on the way to meet her parents with her paramour. They both returned home as the child was born on the road. This was repeated in the case of the second child too. The elder child desired to enter the noble Sangha. He got the younger brother to follow him. But the younger brother paid no heed to reciting. Venerable brother though a mahā arahat having to play the teacher to his younger brother nearly ended badly. Culla Panthaka was asked to memorise a verse of four lines but he was unable to do so for four months with the result the elder brother felt that he was of no use to the dispensation. Culla Panthaka was asked to quit.

So crestfallen Culla Panthaka was sobbing in a corner of the temple. His grief was all the more when his elder brother made preparations to attend an almsgiving to many monks, with Buddha at the head, by Jīvaka the physician, on the following day–less one (meaning himself)

The Buddha came to his rescue. He gave him a piece of linen of spotless white and asked him to stroke it facing the sun saying that nothing is so clean that doesn’t turn impure. The words were Rajoharanam.

In due course, perspiration from the palm of his hand made the cloth exceedingly dirty. The universality of change (anicca) which is the key note of the doctrine of Buddhism was grasped. So Culla Panthaka became an arahat.

At the same time, the latent power was manifested. He got the psychic power to create any number of corporeal figures which was soon put to a practical test. The almsgiving came to pass. Buddha promptly put His hand over the bowl, when food was offered. The reason was that Culla Panthaka, who was left out, should participate. So an attendant was sent to the temple, that was close by, to fetch him. He was amazed to see in the temple over a thousand monks all looking alike. So it was duly reported to Jīvaka who redirected him to say that Culla Panthaka was expected. On the second visit the wonder grew. For as soon as the name of Culla Panthaka was mentioned all the monks began saying “I am Culla Panthaka”. In the meanwhile the alms-giving was held up by the rapidly developing situation. So the attendant was asked by Jīvaka as directed by the Buddha to go again and this time to catch hold of the robe of the first monk nearest to him saying that the Buddha wants Culla Panthaka. When this was done, the temple appeared deserted except for the monk whose robe he was holding. So the younger brother took his due place in the almsgiving. It is to him that the Blessed One turned to tender merit by a short sermon called puññānumodanā in Pāli. Afterwards a discussion ensued among the monks about the feat of the Buddha.