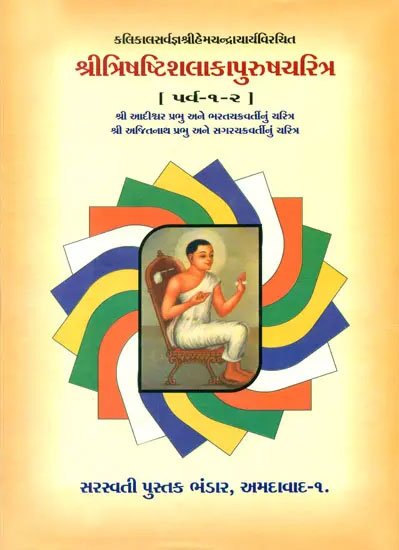

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Story of the truthful bride which is the third part of chapter VII of the English translation of the Mahavira-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Mahavira in jainism is the twenty-fourth Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 3: Story of the truthful bride

“There was an old merchant, a resident of Vasantapura, very poor. He had a grown daughter, suitable for a husband. Mindful of worshipping a god to acquire a good husband, she gathered flowers daily by theft in a certain garden. One day the gardener said, “I will catch the flower-thief today,” and hid himself inside and remained motionless as a hunter. He saw her, who had come as before with confidence, gathering the flowers. She was beautiful and the gardener became agitated. Trembling, he caught her by the arm and, his anger at the taking of the flowers forgotten, said: ‘Best of women, dally with me who have come eager for dalliance. Otherwise I shall not let you go. For I have bought you with flowers.’ The flower-gatherer said to him: ‘Do not, do not touch me with your hand. I am a maiden. I am not yet suitable to be touched by a man, gardener. The gardener said to her: ‘As soon as you are married, you must make this body a vessel of pleasure to me first.’ The girl agreed, ‘Very well,’ and the gardener released her. She went home, her maidenhood unharmed.

One day she was married to a very excellent husband and, when she had gone to the bedchamber at night, said to her husband: ‘Husband, I promised a gardener that as soon as I was married I would go to him first. So give me your permission that I, bound my promise, may go to him. After J have gone to him once, I shall be completely yours.’ She left the bedchamber at once, permitted by her husband saying in astonishment, ‘Oh, she is pure in heart, keeping her promise.’

As she went along the road, wearing ornaments of various jewels, keeping her promise, she was stopped by wicked highwaymen seeking money. She told the story of the gardener as it was and said to the robbers, ‘O brothers, take my ornaments as I return.’ Because of her true story she was released by the thieves who esteemed the keeping of a promise and who said, ‘We will take you as you return.’

Further on she was stopped by a Rākṣasa whose stomach was lean from hunger—she, doe-eyed, like a doe by a lion. Astonished by her true story, the Rākṣasa let her go with the thought, ‘I will eat her when she returns.’

She went to the lustful gardener and said: ‘I am the flower-gatherer. Newly married, I have come to you.’ ‘Oh! she is a good woman, keeping her promise, high-minded.’ With this idea the gardener bowed to her like a mother and let her go.

She returned to the same place where the Rakṣas waited and told him the whole story of how she was released by the gardener. Thinking, “Shall I be inferior in magnanimity to a gardener?” the Rākṣasa let her go, bowing to her like a mistress. She reached the vicinity of the thieves who were watching the road and said, ‘Brothers, all of you take my property.’ She told the whole story of how she had been released by the gardener and how she had been released by the Rakṣas and after hearing that, they said: ‘We are not inferior in magnanimity to a gardener and a Rākṣasa. So go, lady. Good luck to you. You are to be honored. You are our sister.’

The excellent woman went and told her husband the true story of the gardener, the Rākṣasa, and the robbers, just as it happened. After enjoying pleasure with her through the whole night, at sunrise her husband made her mistress of his property. Now, people, after consideration tell me: who did the most difficult thing—the husband, the robbers, the Rakṣas, or the gardener?”

The jealous men among them said: “The husband did the most difficult thing, by whom his bride, intent on love, was sent to another man.” The ones, suffering from hunger said: “The Rākṣasa did the most difficult thing, by whom, though he was very hungry, she was not eaten after she had been caught.” The lovers said, “The gardener did the most difficult thing, since he did not enjoy her after she had come of her own accord in the night.” The mango-thief said, “The robbers did the most difficult thing, since the bride was released with her ornaments intact.”

Abhaya recognised the thief and had him arrested. He asked, “How did you take the mangoes?” The thief replied, “By the power of a charm.” Then Abhaya told it all to the king and handed over the thief. Śreṇika said: “The thief has been found. No one else is looked for. However, this man is powerful; so he must be punished, no doubt.” Abhaya, wishing the king to be free from tricks, said: “Majesty, take the charm from him. Later, what is fitting will be done.”

Then the king of Magadha had the Mātaṅga-chief come before him and began to repeat the charm from his lips. Though the king, seated on the lion-throne, recited it, the charm did not stay in his mind, like water that has fallen on a high place. Then the Lord of Rājagṛha blamed the thief, “There is some deceit on your part, since the charm does not pass over to me.”

Abhaya said: “Majesty, this man is your charm-teacher. A charm becomes manifest to those showing reverence to the teacher, not otherwise. Have this Mātaṅga sit on your own lion-throne, Majesty, and you yourself sit on the ground, after making the aṭjali before him.” For the sake of the charm the king showed him respect. One might get the highest charm even from a low man. That is well-known. The two charms for raising and bending, heard from his lips, remained in the king’s mind, like an image in a mirror. Abhaya pacified the king, making the aṭjali, and had the thief released because he had attained the rank of a charm-teacher.