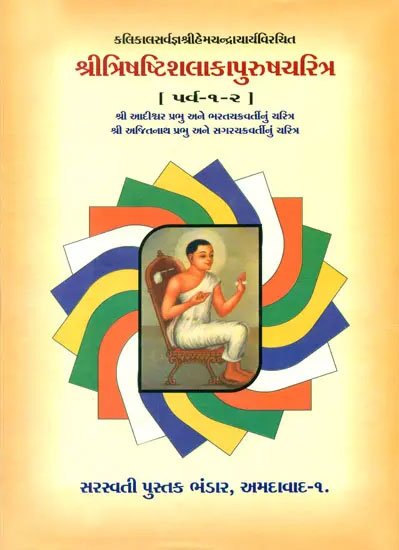

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Mahavira’s childhood which is the third part of chapter II of the English translation of the Mahavira-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Mahavira in jainism is the twenty-fourth Tirthankara (Jina) and one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 3: Mahāvīra’s childhood

After he had sung his praises in these words, Śakra took the Lord and laid him at his mother’s side; and he took away his image and the sleeping-charm. He put a linen garment and a pair of earrings on his pillow; hung above the Lord (on the canopy) a śrīdāmagaṇḍaka,[1] and went to his own dwelling.

Then the Jṛmbhaka-gods, sent by Dhanada at Indra’s order, rained streams of gold and gems[2] on the palace. The king had people released from the prisons at his son’s birth-festival. For the birth of the Arhat was for the release of people from birth.

On the third day, the delighted parents themselves showed the sun and moon to their son. On the sixth day the king and queen observed the festival of the night-vigil with several women of good family who were not widows, singing soft, auspicious songs, with saffron-ointment, beautiful with many ornaments, with wreaths hung around their necks. When the eleventh day had come, Kind Siddhārtha and Queen Triśalā held the festival of the birth-ceremony. On the twelfth day King Siddhārtha, whose wish had been accomplished, summoned all his relatives by birth and marriage. The king rewarded those who made auspicious presents; for he observed the custom of making suitable presents in return.

Siddhārtha said to them: “While this son of mine was in the womb, money, et cetera in the house, city, and country increased. So, gentlemen, let my son be named ‘Vardhamāna.’” “So be it,” they replied, delighted. The other name, ‘Mahāvīra,’ was given the Lord of the World by Indra, saying, “He will surely not tremble even at great attacks.” He was attended by gods and asuras, rivals in devotion, sprinkling the earth, as it were, with his eye raining nectar. Marked with one thousand and eight marks, naturally mature by his qualities, he gradually advanced in age.

One day, when he was less than eight years old, he went to play with princes of his own age at games suitable for their age. Then Had (Śakra), knowing this by clairvoyance, described Vīra in the assembly of the gods, “Even the strong are inferior to Mahāvīra.” A certain god, because he was jealous, said, “I myself will make Vīra tremble,” and went where the Lord was playing. The Lord was playing at āmalakī[3] with the princes and he (the god) assumed the form of a serpent by magic and stood under a tree. Then, terrified, the princes ran here and there; the Lord smiled, picked up the serpent like a rope and threw it on the ground. The princes, ashamed, went there again to play. The god assumed the form of a prince and went there, too, and all climbed a tree. The Lord reached the top of the tree, first of the princes. Yet what is this to him who will reach the top of the universe?[4]

There the Blessed One looked like the sun on the peak of Meru. The others, hanging on the branches, looked like monkeys. The Blessed One won a bet he had made: Whoever should win in this should ride on the backs of the others. Vīra mounted the princes and rode them like horses. Foremost among the strong, he mounted the god’s back also. Then the god with malicious intentions assumed the terrifying form of a goblin and began to grow, exceeding mountains in size. He resembled Takṣaka with his tongue in a mouth equal to Pātāla; he resembled a forest-fire on a lofty peak with tawny hair on the top of his head. Fie had terrible fangs shaped like saws; eyes burning like fireplaces; awful nostrils like caves in mountains; frightful eyebrows curved in frowns like serpents. While he was still growing, the Lord turned him into a dwarf by striking him on the back with his powerful fist. Thus with his own eyes he saw the Blessed One's strength as described by Indra. In his own form he bowed to the Lord and went to his own house.

When he was past eight, the Lord’s father began his education; and at that moment the lion-throne of Biḍaujas shook. Knowing by clairvoyance the remarkable simplicity of his parents, Indra approached him, saying, “The very idea of the Omniscient being a pupil!” The Master was seated on the teacher’s seat by Vāsava with a bow and at his request recited grammar. “This grammar was taught by the Blessed One as teacher to Indra,” and it was called ‘Aindra’ among the people, after hearing that.

The Master gradually attained maturity, seven cubits tall, adorned with a beautiful gait like a forest-elephant. The Lord's beauty was the greatest in the three worlds; his rank was the highest in three worlds; he had fresh manhood; yet there was no change in his nature.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

I am stilt in doubt exactly what a śridāmagaṇḍaka was. PH defines it as ‘a collection of beautiful garlands with the shape of a daṇḍa (pole).’ But that obviously does not fit the description in 1.2.618 and 2.2.507. It was a golden ball adorned with garlands, but the details are not clear. See I, n, 167 and II, n. 104.

[2]:

I think māṇikya is surely ‘gem’ and not specifically ‘ruby’ here.

[3]:

This is probably a boys’ game now played in Gujarat, āmalāpippalī. It might be called ‘touch-and-go.’

[4]:

I.e. Lokāgra, the name of the top portion of the universe occupied by the Siddhas.