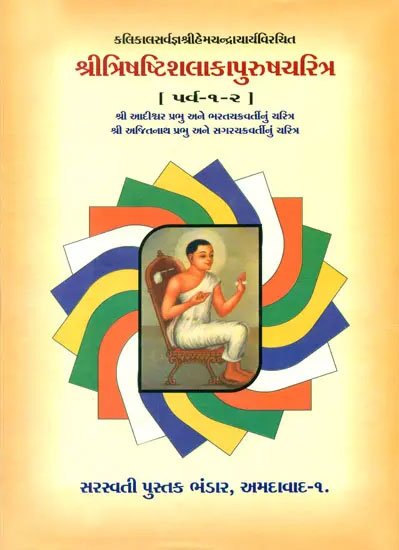

Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra

by Helen M. Johnson | 1931 | 742,503 words

This page describes Previous incarnations of Sanatkumara as King Vikramayashas and of Asitaksha as Nagadatta which is the first part of chapter VII of the English translation of the Sanatkumara-cakravartin-caritra, contained within the “Trishashti Shalaka Purusha Caritra”: a massive Jain narrative relgious text composed by Hemacandra in the 12th century. Sanatkumara-cakravartin in jainism is one of the 63 illustrious beings or worthy persons.

Part 1: Previous incarnations of Sanatkumāra as King Vikramayaśas and of Asitākṣa as Nāgadatta

There is here a city, Kāñcanapura, possessing golden splendor excelling Bhogāvatī, Amarapurī, Laṅkā, et cetera. Its king was Vikramayaśas, whose power was excellent, the lightning of whose splendor increased the rain of the tears of his enemies’ wives. There were five hundred gazelle-eyed women in his household, objects of affection, like cow-elephants of an elephant who is lord of the herd.

At that time there was a very wealthy merchant, Nāgadatta, like a treasury of wealth, in the city. Of him there was a wife, like Śrī of Viṣṇu, possessing charm and grace, endowed with exceeding beauty, named Viṣṇuśrī. They, whose affection for each other was as constant as the color of indigo, passed the time like two sārasas[1] enamored of unhindered love-sport.

In the manner of the crow and the palm fruit,[2] somehow she came one day into the range of vision of King Vikramayaśas. When he saw her, Vikramayaśas, whose wealth of discernment was stolen by Manobhū like a thief, reflected thus in his mind:

“Oh, her eyes are charming like a deer’s; her abundant hair beautiful like a peacock’s tail; her lips soft and red like a ripe bimba in two parts; her breasts full and arched like pleasure-peaks of Smara; her arms straight and soft like young creepers; her waist extremely small, that could be clasped with one hand, like the middle of a thunderbolt; a line of hair, like a row of duckweed; a navel like a whirl-

pool; her hips like a beach in the river of loveliness; her thighs like pillars of plantain; her feet like lotuses; and all the rest of her—whose mind would it not steal? Because his mind was confused by old age, she was bestowed by the Creator unsuitably on some unfit person, like a Śakra-pillar[3] in a cemetery. I shall take her away and place her in my own household. Let the blame for placing her unsuitably pass away from the Creator.”

With these reflections Vikramayaśas, distracted by Kandarpa, took her and disgraced his glory. The king put her in his household and, very attentive, always pleased her with varied love-sports. The merchant was distracted by separation from her, as if he were possessed by a demon, as if he had eaten dhattūra,[4] as if he had caught a disease, as if he had drunk wine, as if he had been smelled by a serpent, as if he had experienced a derangement of the three humors. Time passed, bringing pain and pleasure to the merchant separated from her and to the king united with her.

Because the king constantly delighted in Viṣṇuśrī, the women of the household, angered by jealousy, used sorcery (against her). Because of the sorcery she withered away moment by moment, like a creeper from an ant at its root, and died. The king was dead, as it were, though alive, from her death; lamenting and wailing, he became like Nāgadatta. He did not permit Viṣṇuśrī’s corpse to be thrown into the fire, saying repeatedly, “My wife is pretending silence.” The ministers took counsel and deceived the king. They took Viṣṇuśrī’s body and threw it into the forest. “Just now you were here. Why, beloved, are you not visible? Enough of this game of disappearing, the companion of separation. For the fire of separation, knowing vulnerable points, is not joined with play. Why do you not grieve because of my grief? For we always had one soul. Have you gone alone to some pleasure-stream from curiosity? Or did you ascend a pleasure-mountain, or did you go to a pleasure-garden? How can you play without me? I am coming.”

Talking in this way, the king wandered in various places, as if out of his senses. When three days had passed since he had eaten or drunk, the ministers feared for the king’s life and showed him her body. When he had seen Viṣṇuśrī’s body, with its hair exceedingly disordered like a bear, with its eyes pecked out by wild herons, like a hare in the grass,[5] with its breasts chewed by vultures eager for flesh, all its intestines pulled out by jackals, having an unlovely appearance, covered with swarms of flies like sweet rice-water, filled with ants like a dish of eggs broken by a fall, smelling of putrefaction, Vikramayaśas at once became disgusted with existence and reflected:

“Oh! there is nothing whatever of value in this worthless worldly existence. For how long a time have we been deluded by the idea of value in her, alas! No one who knows the highest good, indeed, is ensnared by women with qualities that are purely incidental like the color of turmeric. Women covered by skin are charming outside, filled with liver, excrement, impurities, phlegm, marrow, and bone, fastened together by muscles. If there could be a transposition of the outside and inside of a woman’s body, its lover would conceal (within himself) a vulture and jackal. If Kama wishes to conquer the world with women as a weapon, why does he, confused in mind, not take a weapon in the form of a small feather? I will root up completely the root of desire for that love by which, alas! everything is transformed.”

With these reflections, disgusted with saṃsāra, noble-minded, he went and took initiation at the feet of Ācārya Suvrata. Free from interest in the body, he dried himself up by penances of one day, two days, a month, et cetera, as the sun dries up water by its rays. After practicing severe penance, in course of time he died and became a chief-god in Sanatkumāra with a maximum life.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

See I, n. 130. The sārasa is the Ardea Sibirica, the blue Indian crane.

[2]:

By chance.

[3]:

A decorated wooden pillar used in the festival to Indra, now obsolete. See I, 343.

[4]:

The Datura, the seeds of which are one of the most common and deadly poisons of India. Watt, p. 488, says that the seeds “enter into the composition of certain alcoholic beverages and render the consumers of these literally mad.”

[5]:

Read śaśavaccaśare with one MS. See App. I.