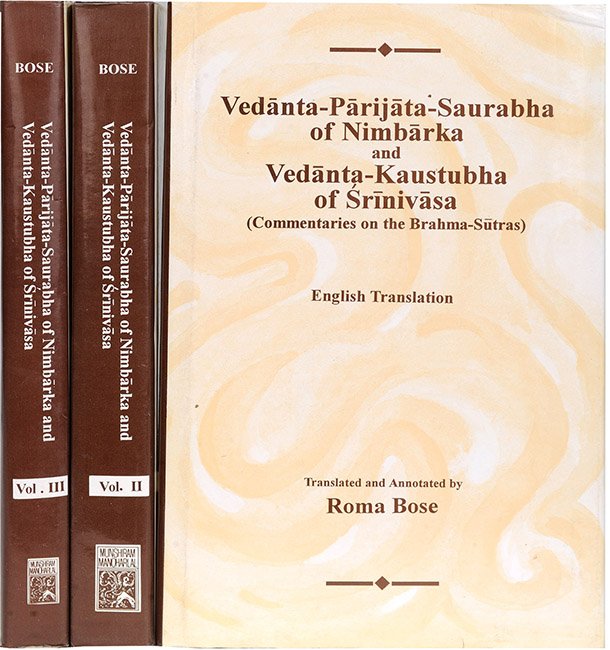

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 2.3.17, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 2.3.17

English of translation of Brahmasutra 2.3.17 by Roma Bose:

“The soul (does) not (originate), on account of nonmention in scripture, and on account of eternity (known) therefrom (i.e. from scriptural texts).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

The individual “soul” does not originate. Why? Because there is no text about its having origin by nature; and because from the scriptural texts: ‘A wise man is neither born nor dies’ (Kaṭha-upaniṣad 2.18[1]), ‘Eternal among the eternal’ (Kaṭha-upaniṣad 5.13[2]), ‘An unborn one, verily, lies by, enjoying’ (Śvet, 4.5[3]) and so on, the eternity of the individual soul is known.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

If it be argued: In conformity with the texts: ‘One desirous of heaven should perform sacrifices’ (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 2.5.5[4]), etc., which lay down the means to attaining lordship in the next world, let the designation: ‘Devadatta is born and dead’ refer to the birth and death of the body. But like the ether and the rest, birth and death must pertain to the individual soul as well at the time of creation and dissolution (respectively). Thus there is no conflict whatsoever with any text.—

We reply: “Not, the soul, on account of non-mention in Scripture”. The singular number ‘soul’ implies the class,[5] in accordance with the scriptural text teaching the plurality of souls, viz. ‘Eternal among the eternal, conscious among the conscious’ (Kaṭha-upaniṣad 5.13; Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 6.13), and in accordance with the aphorism, to be mentioned hereafter, viz. “And on account of non-continuity, there is no confusion” (Brahma-sūtra 2.3.48). The soul is not born, nor dies. Why? ‘On account of non-mention in Scripture’, i.e. because there are no scriptural texts designating the birth and death (of the soul) at the time of creation and dissolution; and, because on the contrary, “the eternity” of the soul is known “therefrom”, i.e. from the scriptural texts like: ‘“Imperishable, verily, O! is this soul, possessing the virtue of being indestructible”’ (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.5.14), ‘A wise man is neither born, nor dies’ (Kaṭha-upaniṣad 2.8),‘Eternal among the eternal, the conscious among the conscious, the one among the many, who bestows objects of desires’ (Kaṭha-upaniṣad 5.13; Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 6.13), ‘The two unborn ones, the knower and the non-knower, the lord and the non-lord’ (Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 1.9), ‘One unborn one, verily, lies by, enjoying. Another unborn one leaves her who has been enjoyed’ (Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 4.5) and so on; as well as from the following Smṛti passages, viz. ‘“Nor at any time, verily, was I not, nor you, nor these lords of men; nor, verily, shall we ever not be hereafter”’ (Gītā 2.12), ‘“Unborn, eternal, constant and ancient, he is not killed when the body is killed”’ (Gītā 2.20), ‘“Who knows him to be imperishable, eternal, unborn and immutable, how can that man kill one, O Pārtha, or cause one to be killed?”’ (Gītā 2.21) and so on.

If it be objected: There are scriptural texts designating the origin of the world together with the sentient, such as, ‘All come forth from this soul’, ‘Born of whom, the progenitress of the universe let loose the souls with water on the earth’ (Mahānārāyaṇa-upaniṣad 1.4), ‘The lord of beings created beings’ (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 1.1.10,1[6]) ‘“All these beings, my dear, have Being as their root, Being as their abode, Being as their support”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.4), “‘From whom, verily, these beings arise, through whom they live when born, to whom they go and enter”’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 3.1) and so on. Hence, the denial of birth and death of the individual soul is not reasonable. For this very reason, the initial proposition that through the knowledge of one there is the knowledge of all, is established,—

(We reply:) “No”, because the quoted texts teach that individual soul has an origin, which (is not actual origin, but simply) consists in the expansion of its knowledge, caused by its connection with the body, subsequent to its giving up its real nature at the time of dissolution. If this be so, then the individual soul too being an effect of Brahman, the above initial proposition is established. And hence, it is established that Brahman, who in His causal state possesses the non-divided names and forms as His powers and is without an equal or a superior,—in accordance with the text: ‘“The existent alone, my dear, was this in the beginning, one only, without a second”’ (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.2.1),—comes Himself, as possessed of the manifest names and forms as His powers at the time of the production of effects, to abide as threefold, viz. in the forms of the enjoyer (i.e. the cit), the object enjoyed (i.e. the acit) and the controller (i.e. Brahman). There is no contradiction here by any text whatever.

Here ends the section entitled “The soul” (7).

Comparative views of Rāmānuja, Śrīkaṇṭha and Baladeva:

They read “śruteḥ” instead of “aśruteḥ”[7]. Interpretation same.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Quoted by Śaṅkara, Rāmānuja, Śrīkaṇṭha and Baladeva.

[2]:

Quoted by Rāmānuja, Śrīkaṇṭha and Baladeva.

[3]:

Not quoted by others.

[4]:

P. 208, line 27, vol. 2.

[5]:

And not that there is only one soul.

[6]:

P. 23, line 16, vol. 1.

[7]:

Śrī-bhāṣya (Madras edition) 2.3.18, p. 136, Part 2; Brahma-sūtras (Śrīkaṇṭha’s commentary) 2.3.18, p. 140, Parts 7 and 8; Govinda-bhāṣya 2.3.16.