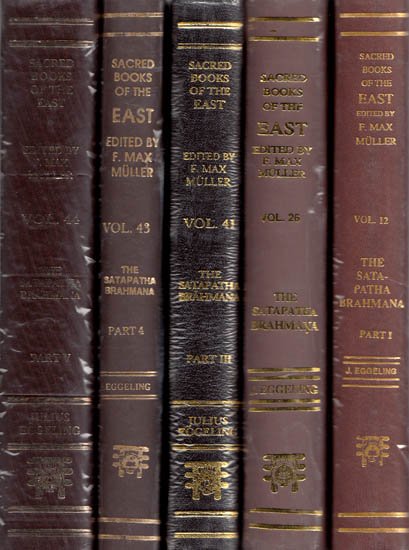

Satapatha-brahmana

by Julius Eggeling | 1882 | 730,838 words | ISBN-13: 9788120801134

This is Satapatha Brahmana VIII.2.3 English translation of the Sanskrit text, including a glossary of technical terms. This book defines instructions on Vedic rituals and explains the legends behind them. The four Vedas are the highest authortity of the Hindu lifestyle revolving around four castes (viz., Brahmana, Ksatriya, Vaishya and Shudra). Satapatha (also, Śatapatha, shatapatha) translates to “hundred paths”. This page contains the text of the 3rd brahmana of kanda VIII, adhyaya 2.

Kanda VIII, adhyaya 2, brahmana 3

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

1. He then lays down the Prāṇabhṛt (bricks). For at that time the gods said, 'Meditate ye!' whereby, doubtless, they meant to say, 'Seek ye a layer!' Whilst meditating, they saw even that layer, the wind: they put it into that (fire-altar), and in like manner does he (the priest) now put it therein.

2. He lays down the Prāṇabhṛts,--wind, doubtless, is breath: it is wind (air) he thus bestows Upon him (Agni). On the range of the Retaḥsic (they are placed); for the Retaḥsic are these two (worlds): it is within these two (worlds) that he thus places the wind; whence there is wind within these two (worlds).

He places them on every side: he thus places wind on all sides, whence the wind is everywhere. [He places them so as] on every side to run in the same direction[1]: he thus makes the wind everywhere (to blow) in the same direction, whence, having become united, it blows from all quarters in the same direction. He lays them down alongside of the regional (bricks)[2]: he thereby places the wind in the regions, whence there is wind in all the regions.

3. And, again, as to why he lays down the Prāṇabhṛts;--it is that he thereby bestows vital airs on these creatures. He places them so as not to be separated from the Vaiśvadevīs: he thereby bestows vital airs not separated from the creatures. [He lays them down with, Vāj. S. XIV, 8], 'Preserve mine up-breathing! Preserve my down-breathing! Preserve my through-breathing! Make mine eye shine far and wide! Make mine ear resound!' He thereby bestows on them properly constituted vital airs.

4. He then lays down the Apasyā (bricks). For the gods, at that time, spake, 'Meditate ye!' whereby, doubtless, they meant to say, 'Seek ye a layer!' Whilst meditating, they saw even that layer, rain:

they put it into that (fire-altar) and in like manner does he now put it therein.

5. He put on the Apasyās; for rain is water (ap); it is rain he thereby puts into it (the altar; or into him, Agni). On the range of the Retaḥsic (he places them), for, the Retaḥsic being these two (worlds), it is on these two (worlds) that he thereby bestows rain, whence it rains therein. He places them on every side: he thus puts rain everywhere, whence it rains everywhere. [He places them] so as everywhere to run in the same direction[3]: he thereby bestows rain (falling) everywhere in the same direction, whence the rain falls everywhere, and from all quarters, in the same direction. He places them alongside of those referring to the wind[4]: he thereby puts rain into the wind, whence rain follows to whatever quarter the wind goes.

6. And, again, as to why he lays down Apasyās,--he thereby puts water into the vital airs. He places them so as not to be separated from the Prāṇabhṛts: he thus places the water so as not to be separate from the vital airs. Moreover, water is food: he thus introduces food not separated from (the channels of) the vital airs. [He lays them down with, Vāj. S. XIV, 8], 'Make the waters swell! Quicken the plants! Bless thou the two-footed! Protect the four-footed! Draw thou rain from the sky!' He thereby puts water that is made fit, into those (vital airs).

7. He then lays down the Chandasyā[5] (bricks) for the gods, at that time, spake, 'Meditate ye!' whereby, doubtless, they meant to say, 'Seek ye a layer!' Whilst meditating, they saw even that layer, cattle (or beasts): they put it therein, and, in like manner, does he now put it therein.

8. He lays down the Chandasyās; for the metres (chandas) are cattle: it is cattle he thus puts into it (or, bestows on him, Agni). On every side (he places them): he thereby places cattle (or beasts) everywhere, whence there are cattle everywhere. He places them alongside of the Apasyās: he thus establishes the cattle on (or, near) water, whence cattle thrive when it rains.

9. And, again, as to why he lays down Chandasyās. When Prajāpati was relaxed, the cattle, having become metres, went from him. Gāyatrī, having become a metre, overtook them by dint of her vigour; and as to how Gāyatrī overtook them, it is that this is the quickest (shortest) metre. And so Prajāpati, in the form of that (Gāyatrī), by dint of his vigour, overtook those cattle.

10. [He lays down four in front, with, Vāj. S. XIV, 9], 'The head is vigour,'--Prajāpati, doubtless, is the head: it is he that became vigour;--'Prajāpati the metre,'--Prajāpati indeed became a metre.

11. 'The Kṣatra is vigour,'--the Kṣatra, doubtless, is Prajāpati, it is he that became vigour;--'the pleasure-giving metre,'--what is undefined that is pleasure-giving; and Prajāpati is undefined, and Prajāpati indeed became a metre.

12. 'Support is vigour,'--the support, doubtless, is Prajāpati: it is he that became vigour;--'the over-lord the metre,'--the over-lord, doubtless, is Prajāpati, and Prajāpati indeed became a metre.

13. 'The All-worker is vigour,'--the All-worker, doubtless, is Prajāpati: it is he that became vigour;--'the highest lord the metre,'--Prajāpati, the highest lord, doubtless, is the waters, for they (the waters of heaven) are in the highest place: Prajāpati, the highest lord, indeed became a metre.

14. These then are four kinds of vigour, and four metres; this (makes) eight,--the Gāyatrī consists of eight syllables: this, assuredly, is that same Gāyatrī in the form of which Prajāpati then, by his vigour, overtook those cattle; whence they say of worn-out cattle that they are overtaken by vigour (or, age), and hence (the word) 'vigour' recurs with all (these bricks). And those cattle which went away from him (Prajāpati) are these fifteen other (formulas): the cattle are a thunderbolt, and the thunderbolt is fifteenfold: whence he who possesses cattle, drives off the evildoer, for the thunderbolt drives off the evildoer for him. And in whatever direction, therefore, the possessor of cattle goes, that he finds torn up by the thunderbolt.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

That is, the bricks placed in opposite quarters, run in the same direction; see p. 26, note 3.

[2]:

The Prāṇabhṛts are placed beside the Vaiśvadevīs so as to be separated from them by the respective section of the anūkas or 'spines' (dividing the square 'body' of the altar into four quarters). Each Vaiśvadevī would thus be enclosed between an Āśvinī and a Prāṇabhṛt; but whilst the Āśvinī and Vaiśvadevī are placed in the same section (or quarter) of the altar, the Prāṇabhṛt comes to lie in the adjoining section, moving in the sunwise direction from left to right.

[3]:

See p. 26, note 3.

[4]:

. The five Apasyā bricks are placed immediately to the right of the Prāṇabhṛts (looking towards the latter from the centre of the altar), so as to fill up the four remaining spaces between the four sets of bricks on the range of the Retaḥsic.

[5]:

These are otherwise called Vayasyā (conferring vigour, or vitality), each formula containing the word vayas, 'vitality, force.' There are nineteen such bricks which are placed on the four ends of the two 'spines,' viz. four on the front, or east end of the spine proper, and five on the hind end of it as well as on each end of the 'cross-spine.'