Manasara (English translation)

by Prasanna Kumar Acharya | 1933 | 201,051 words

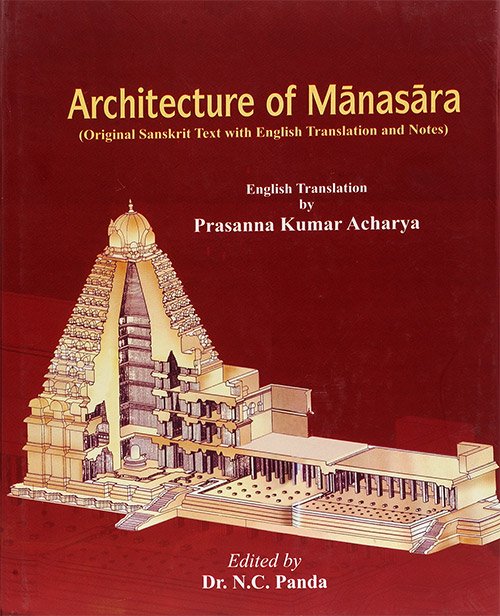

This page describes “history of publication” which is Preface 1 of the Manasara (English translation): an encyclopedic work dealing with the science of Indian architecture and sculptures. The Manasara was originaly written in Sanskrit (in roughly 10,000 verses) and dates to the 5th century A.D. or earlier.

Part 1 - History of publication

Architecture of Mānasāra is an English version of a Sanskrit text of that name edited, with critical notes, for the first time by the writer. The text is based on all the eleven available manuscripts gathered together by the then Secretary of State for India, Sir Austin Chamberlain, for the use of the writer. Except one, all other manuscripts are fragmentary and none contains any commentary, drawings, diagrams or sketches. The buildings of the time, religious, military, or residential, do not appear to exist in their entirety for a ready reference. In 1838 Ram Raz based his Essay on Architecture of the Hindus on a few chapters of a single fragmentary manuscript. In recent years several other scholars have quoted extracts from one or other of the manuscripts, but no one, including Ram Raz, attempted the translation of any passage. A few Sanskrit texts of architecture have also been printed in the recent years, but none has been translated into English or elucidated in any other language, Indian or European.

It was the great Director General of Archaeology, Sir John Marshall, who conceived the idea, and advised Lord Pentland, the then Governor of Madras, to get a reliable version of the standard work on Indian architecture scientifically edited and properly elucidated, together with sketches, diagrams, and measured drawings, when he (Sir John Marshall) came to know, through Dr. F. W. Thomas, then Librarian of the India Office, London, that I had been working for some time as a Government of India Slate scholar on the subject in consultation with Mr. E. B. Havell and under the guidance of Dr. L. D. Barnett of the British Museum, Dr. Thomas himself, and Dr. J. Ph. Vogel of Leyden. But the unfortunate coincidence of His Excellency’s retirement and Sir John’s absence from India at the time of my arrival in Madras upset the preliminary arrangement made for the publication from Madras. On my appointment to the Indian Educational Service in the United Provinces, Sir Claude F. de la Fosse, the then Director of Public Instruction, and the first Vice-Chancellor of the reconstructed Allahabad University, took up the matter with scholarly interest and induced the great educationist Governor, Sir Harcourt Butler, to sanction the publication on behalf of the United Provinces Government, through the Oxford University Press.

The work of seventeen years—which Professor E. J. Rapson of Cambridge University correctly predicted to be a life’s undertaking—has thus reached its present destination. It is, however, not the end, but the beginning, of a new line of Indology which, it may perhaps be hoped, is likely to prove not merely of cultural and historical interest, but possibly of some practical benefit to the country and to the nation. Our architectural policy of the past few hundred years, based as it has been on foreign imitation, and in an entirely different climate and soil, has not proved quite successful in regard to temples and humble dwelling-houses, if not in regard to public edifices also. That the sole object of a work like the Mānasāra was primarily and ultimately practical in giving general as well as special guidance to the builders of that time, as also of the future generations, will be clear even to the casual reader of the book. Whether or not the extant structures which have been restored to the nation by the activity of the Archaeological Department, or which having defied the effect of time and weather, are yet standing almost in their original grandeur, will indicate the application of the rules and regulations, or at least the methods and principles laid down in the Mānasāra, remains to be proved. If, after making allowance for existing conditions and requirements, the methods and principles, as well as the rules and regulations laid down in the standard treatise, are found to be scientifically sound and suitable for modem buildings, big and small, they may be experimented with, and the solution of the problems relating to its textual imperfection and historical uncertainty may be left to the care of those whose mission is the elucidation of the past culture.

The preliminary accounts of the subject published in the writer’s Dictionary of Hindu Architecture and Indian Architecture according to Mānasāra Śilpa-śāstra have awakened a world-wide interest as will be seen from the extracts from reviews and opinions appended at the end of the present volume. This has emboldened me to publish as complete a record as is at present practicable. ‘But the reader must understand that these volumes do not claim to be other than provisional. In the nature of things it could not be otherwise. These volumes may open up a new line of Indian achievement and may lead to a task which is just begininng. Fresh materials, facts, and figures are likely to come to light. In such conditions any approach to finality is out of the question.’