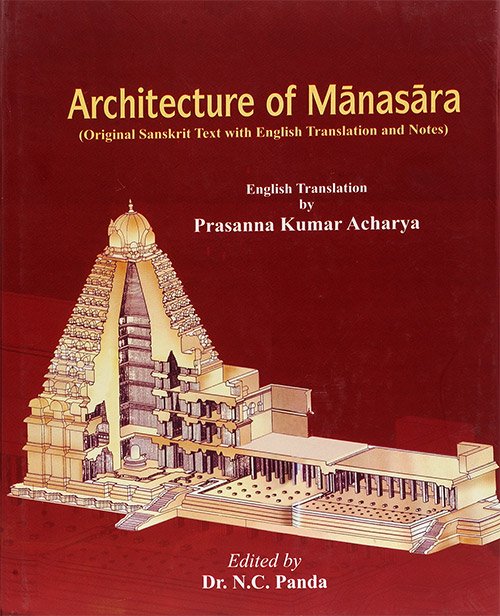

Manasara (English translation)

by Prasanna Kumar Acharya | 1933 | 201,051 words

This page describes “preparation of the plates” which is Preface 2 of the Manasara (English translation): an encyclopedic work dealing with the science of Indian architecture and sculptures. The Manasara was originaly written in Sanskrit (in roughly 10,000 verses) and dates to the 5th century A.D. or earlier.

Part 2 - Preparation of the plates

Owing to the defective nature of the text, which has been shown elsewhere, one can hardly be perfectly sure of the interpretation. An elaborate effort, involving great expenditure of time, money, and convenience, was made to get into contact with the so-called traditional builders ṃ the south, in the Orissan countries, in the Indian States of Rajputana, Central India, Gujarat, Bombay, in the Frontier Provinces, and in the Hill States, in company with trained and experienced engineers, architects, and interpreters, in the vain hope of getting some light from salats. These salats are stated to build in accordance with an ancient tradition which. they claim, to have inherited orally in some cases, but mostly from some fragmentary manuscripts that they have frequently failed to interpret.

Another effort, extending over many years and made through many agencies, both official and non-official, to engage the services, against tempting payment, of teachers or advanced students of the few schools of arts and architecture in the Indian States and elsewhere, mostly under the Government, ended also in failure.

In these circumstances, when it was about to be finally decided to publish this first edition without any illustrations, Mr. H. Hargreaves, the then Director General of Archaeology, in camp at Sanchi, while taking rest in the evening, possibly in a meditative mood concerning ancient monuments, was moved by my tale which had been once before related to him at his palatial office at New Delhi. He very definitely disagreed with my intention of bringing out such a volume without illustrations, and readily accepted my request to place at my disposal the services of Mr. S. C. Mukherji, b.a., g.d.arc., a.i.i.a., then a research scholar of the Archaeological Department, whose name had been mentioned to me by his (Mr. Hargreaves’) personal assistant, Mr. B. T. Mazumdar, and who was subsequently recommended by Mr. R. L. Bansal, a very enthusiastic engineer of the Public Works Department. As an experienced officer of his exalted position, Mr. Hargreaves stipulated, however, that Mr. Mukherji’s services might be available only for a limited period and that I must be present while Mr. Mukherji would be working at his (Mr. Hargreaves’) office at Simla, obviously to get the fullest advantage of a joint effort of his whole department and my own.

Mr. Mukherji himself undertook the task with the greatest possible enthusiasm. He had graduated with Sanskrit and ancient history and received training in the method and principle of Graeco-Roman and modem architecture. As a part of his training, he had been taken under proper guidance round Nasik, Madura, and other places where ho had to examine and sketch ancient Hindu and Muhammadan buildings. He came to know of the Mānasāra at the Agra branch of the Archaeological Department, wherefrom Mr. R. L. Bansal used to take books in connexion with the measured drawings he had been making to illustrate the preliminary chapters of the Mānasāra. Thus Mr. Mukherji eagerly undertook the task when Mr. Bansal could no longer continue with it.

Mr. Bansal, after his training at Roorkee Engineering College, had been in charge of roads and buildings for several years before he started to make observations, in consultation with Dr. Gorakh Prasad, D.SC., the Reader in Astronomy at Allahabad University, on the astronomical calculation of the Mānasāra in connexion with the dialling and orientation of buildings. Mr. Bansal also accompanied me in my tour over Rajputana, including Puṣkar, Mount Abu, and Jaipur, where he studied and made copies and sketches of old structures in order to ascertain the exact nature of the mouldings that are frequently referred to in the Mānasāra. Mr. Bansal’s drafts on these objects have been accepted without much alteration and have been finally drawn by Mr. Mukherji. I shall ever remain grateful to Mr. Bansal and Dr. Gorakh Prasad for their very valuable assistance in doṃg foundation work for the architectural drawings.

For the first three months, Mr. Mukherji and myself worked together at the rate of nearly sixteen hours a day. As a result of this hard work Mr. Mukherji was able to make drafts of the more important chapters, including the one dealing with pillars and columns. The first fruit of his labour apparently satisfied Mr. Hargreaves, who took round Mr. Mukherji’s studio big officials, including Sir Frank Noyce, the then Educational Secretary, Mr. A. H. Mackenzie, then Commissioner of Education, and others, in order to explain to them the revelation of the Mānasāra. Mr. Mukherji has worked on these drawings for over two years and has earned nay everlasting gratitude. Words fail me to express my indebtedness to Mr. Hargreaves and the Archaeological Department, without whose assistance these drawings could not have been prepared.

Thus it can be expected that all preliminary precautions that have been taken at every stage in the execution of the architectural drawings may ensure a faithful representation in lines of what Mānasāra expressed in words. The measured drawings, one hundred and thirty-five in number, are appended as illustrations but represent only a fraction of those architectural objects that arc actually described in detail. In any event these drawings will supply the much needed materials to determine whether the extant monuments of Hindu architecture were based on the methods and principles governing the details of the village scheme, town-planning, forts and fortresses, and temples, military buildings, gorgeous palaces and humble residential dwellings of various sizes and measures described in the Mānasāra.

The sculptural drawings in line and in colours could not be given the same advantage of joint deliberation, mutual consultation, and final revision. Despite the fact that there is an ever-growing class of artists all over India, most of those of local renown and teachers of recognized schools of arts in Bombay, Baroda, Delhi, Lahore, Lucknow, Allahabad, Ajmer, Jaipur, Jodhpur, Calcutta, Shillong, Cuttack, Puri, Madras, and Bangalore refused, after due deliberation, to undertake the work; and the few artists who agreed, on their own terms, gave up the task after trials lasting from two to three months. At last Professor M. H. Krishna, m.a., D.Litt., Director of Archaeology, Mysore State, took me to several local artists and undertook to select one for me. But after protracted negotiations lasting over eight months he gave up in disgust the prospect of finding a reliable person for the purpose, declaring that “our old type artists are so old-worldly in their business habits.” But I am thankful to him for having brought me in contact with Śilpa Siddhanti Śivayogi Śrī Siddalingaswamy, the head of the Jagadguru Nagalingaswamy monastery, who claims to be “a Śilpin by heredity,” to have “studied Śilpa, painting, etc., at the feet of Guru” and to have been “training for a quarter of a century a number of youths in the art of sculpture, painting, and kindred subjects according to Śāstric canons.” He undertook, after an experiment lasting for nearly a year, to supply twenty-two drawings on which another six months were spent. I believe that he has given the best of his inherited skill, ripe experience, and spiritual study of the subject to these sculptural drawings.

In the absence of the expected assistance and personal supervision of Dr. Krishna, the elucidation of the details had to be carried out in lengthy, and, at times, trying correspondence. I shall, however, remain grateful to Śilpa Siddhanti Śivayogi Śrī Siddalingaswamy who, among all the artists I had approached, had the courage and patience of partly illustrating the sculptural section of the Encyclopaedia of Hindu Arts, and hopes to execute the remaining sculptural drawings, numbering some three hundred, if his present performance proves successful and. if the Mānasāra itself receives the practical recognition it deserves.