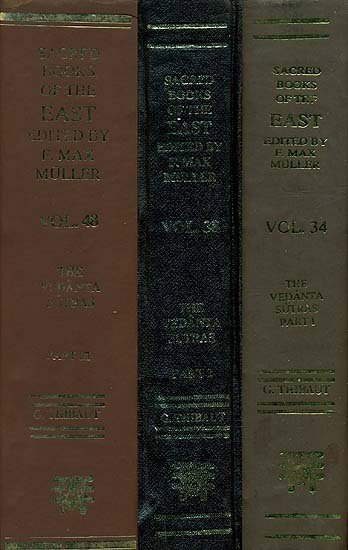

Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 2.2.5

5. And if you say—as the man and the stone; thus also.

Here the following view might be urged. Although the soul consists of mere intelligence and is inactive, while the Pradhāna is destitute of all power of thought; yet the non-sentient Pradhāna may begin to act owing to the mere nearness of the soul. For we observe parallel instances. A man blind but capable of motion may act in some way, owing to the nearness to him of some lame man who has no power of motion but possesses good eyesight and assists the blind man with his intelligence. And through the nearness of the magnetic stone iron moves. In the same way the creation of the world may result from the connexion of Prakṛti and the soul. As has been said, 'In order that the soul may know the Pradhāna and become isolated, the connexion of the two takes place like that of the lame and the blind; and thence creation springs' (Sāṅkhya Kā. 21). This means—to the end that the soul may experience the Pradhāna, and for the sake of the soul’s emancipation, the Pradhāna enters on action at the beginning of creation, owing to the nearness of the soul.

To this the Sūtra replies 'thus also.' This means—the inability of the Pradhāna to act remains the same, in spite of these instances. The lame man is indeed incapable of walking, but he possesses various other powers—he can see the road and give instructions regarding it; and the blind man, being an intelligent being, understands those instructions and directs his steps accordingly. The magnet again possesses the attribute of moving towards the iron and so on. The soul on the other hand, which is absolutely inactive, is incapable of all such changes. As, moreover, the mere nearness of the soul to the Pradhāna is something eternal, it would follow that the creation also is eternal. If, on the other hand, the soul is held to be eternally free, then there can be no bondage and no release.