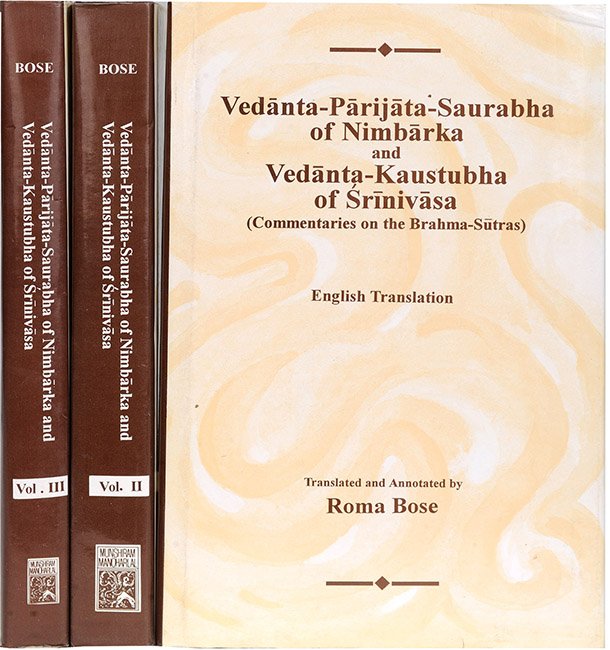

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 4.1.3, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 4.1.3

English of translation of Brahmasutra 4.1.3 by Roma Bose:

“But ‘the self’—so (they admit and make others) understand.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

“This is my self” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.3, 4[1])—so the previous teachers “admit”. “This is your self” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.4.1, etc.[2]), so they teach the disciples. Hence the Highest Person is to be meditated on by one desirous of salvation as one’s own self.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

In the immediately adjoining section, it has been shown that the means are to be practised more than once. This suggests an absolute difference between the knower and the object known. Now we hasten to remove this misconception.

The doubt is as to whether the object to be known, viz. Brahman, is to be meditated on as different from the knower or as the self of the knower ? With regard to it, the prima facie view is: As different. Why? For the following reasons: First, the self, being within the range of the perception of the ‘I’, is easily knowable. Secondly, the means are, on the contrary, enjoined to be repeated more than once for knowing the self in question. Thirdly, there are a great many scriptural and Smṛti texts as well as aphorisms teaching a fundamental difference between Brahman and the individual soul like: “And on account of the designation of difference” (Brahma-sūtra 1.1.18), “But something more, on account of the indication of difference” (Brahma-sūtra 2.1.21) and so on. In this way, such a difference between Brahman and the individual soul being established by the direct evidence of one’s own realization, as well as by Scripture, no other supposition is to be made, in accordance with the condemnatory statement: “He who supposes the self to be otherwise than what it really is,—-what sin is not committed by him, the thief, the stealer of his own self?”

With regard to it, we reply: “But ‘the self’—so (they) admit”, since the Highest self is the whole of which the individual self is a part and since the former is the very soul of the latter, which can have no existence and activity independently of Him, just as the thousand-rayed sun, having independent existence and activity in contrast to its own rays, is their soul, and the rays are non-different from it. Similarly, the Lord should be known to be non-different from the individual souls.

The word “but” indicates clearly the difference in nature between the individual soul and the Highest self, the non-knowing and the allknowing. The relation of identity is possible between two things when they are non-different in some way or other. No identity is possible between a cow and a horse. Again, identity is not possible in the case of a single horse also. But there is a relation of identity between the effect and its cause, the attribute and its substratum, the power and its possessor,—i.e. only between two things which are both different and non-different. Otherwise, in accordance with the text: “All this, verily, is Brahman” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.1), the universe, consisting of the sentient and the non-sentient, must be non-different from Brahman in nature, which is impossible.

Hence, the Lord is the soul of the meditating devotee,—a part of Brahman and different, indeed, from Him in nature,—as the tree is of the leaf, the substratum of light of light, the chief vital-breath of the sense-organs. Hence, both difference and non-difference are equally fundamental and natural. Thus, alone, texts like: “Thou art me, O lord Deity! I am ‘Thou’” and so on can have a meaning. For this very reason, again, the non-difference of the individual soul from Brahman being established,—as of the leaf from the tree, light

from its substratum,—texts like: “He who worships another deity, (thinking:) ‘The Deity is one, I another’, does not know, like a beast” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 1.4.10) and so on, too, fit in. Since between Brahman and the individual soul there is a non-difference of this kind which is not in conflict with difference, there is no contradiction of scriptural and Smṛti passages and aphorisms like: “The conscious among the conscious” (Kaṭha 5.18; Śvetāśvatara-upaniṣad 6.13), ‘“And I am superior to the imperishable as well’” (Gītā 15.18), “But on account of the teaching of something more” (Brahma-sūtra 3.4.8), “Not the other, on account of inappropriateness” (Brahma-sūtra 1.1.17) and so on, the relation of difference-nondifference between the two being approved by all Scriptures. Hence “This is my self” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 3.14.3, 4), “This is the inter soul of all beings” (Muṇḍaka-upaniṣad 2.1.14),—so the previous teachers admit. “This is your soul, within all” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.4.1, 2; 3.5.1), “This is your self, the inner controller, immortal” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 3.7.3, etc.), ‘“All this has that for its soul... Thou art that’” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 6.8.7) and so on,—so they teach their disciples the very same thing. In accordance with the Smṛti passage as well, viz. ‘“ī am the soul, O thick-haired one! dwelling within the heart of all beings’” (Gītā 10.20), ‘“Know me also as the knower of the field”’[3] (Bhagavad-gītā 13.2), it is established that the Highest Person is to be meditated on as one’s own self.

Here ends the section entitled “Meditation under the aspect of self” (2).

Comparative views of Baladeva:

He omits the “ca”.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Quoted by Śaṃkara

[2]:

Quoted by Śaṃkara Rāmānuja and Bhāskara.

[3]:

I.e. the individual soul, the knower of the body.