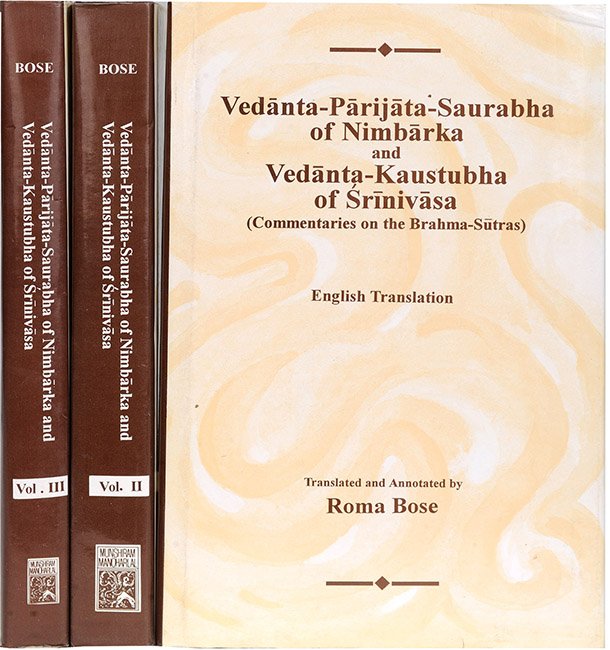

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.3.29, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.3.29

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.3.29 by Roma Bose:

“For this very reason, the eternity (of the Vedas follows).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

The creation by Prajāpati is preceded by the (Vedic) word.

“For this” reason the “eternity” of the Veda is established.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Having apprehended the objection, viz.: In spite of the eternity of the Veda,—it not being mentioned as something created,—the Vedic words, denoting the forms of gods and the rest, are concerned with non-eternal objects; and having removed the consequent false notion regarding the non-eternity of these as well,[1] the author is confirming, incidentally, the eternity of the Veda.

“The eternity” of the word, i.e. of the Veda, follows “for this very reason”, i.e. also because of its priority to the creation by Prajāpati. Words like ‘Vaiśvāmitra’, ‘Kāṭhaka’ and so on etymologically mean simply what has been uttered by them. Thus ‘what has been said by Viśvāmitra is Vaiśvāmitra’, ‘what has been said by Kaṭha is Kāṭhaka’, and so on. At the end of the universal dissolution, Prajāpati, having conceived the forms, powers and the rest of Viśvāmitra and others from the Vedic words ‘Viśvāmitra’, etc. mentioned in texts like: ‘He chooses the maker of sacred formula’, ‘This is a hymn of Viśvāmitra’ (Taittirīya-saṃhitā 5.2.3[2]) and so on; and having created them as endowed with those particular forms and those particular powers, appoints them to the task of revealing those particular sacred formulae (mantras).

Thus given the powers by him, they too, having practised suitable penances, read the sacred formulae,—which form portions of the Veda, which are eternally existent, and which were revealed by Viśvāmitra and others of former ages,—perfect in their sounds and accents without having read them or learnt them from the recitation of a teacher. As such, though they are makers of the sacred formulae, the eternity of the Veda is perfectly justifiable.[3]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

That is, since the Vedic words denote non-eternal objects, it might be thought that these words themselves are non-eternal.

[2]:

P. 24, lines 21-22, vol. 2.

[3]:

That is, the Vedic mantras are said to be composed by different sages like Viśvāmitra and so on; and hence it may be thought that these sages being non-eternal, the mantras composed by them must also be so, i.e. the Veda must be non-eternal. But the fact is that the sages are not really the composers of the mantras, which are really eternal; but when they are said to be the composers of those mantras, it is simply meant that they utter, i.e. reveal the eternally existent mantra in different ages. Thus, e,g. Viśvāmitra in one particular age utters a mantra which is then said to be Vaiśvāmitra. Then, in course of time, Viśvāmitra perishes, but the mantra remains intact; and in the next age, a new Viśvāmitra is deputed to utter and reveal the very same mantra and so on. Thus, the mantra itself remains unchanged from all eternity, only its revealers change from age to age. Hence the Vedic mantras are really eternal and so is the Veda.