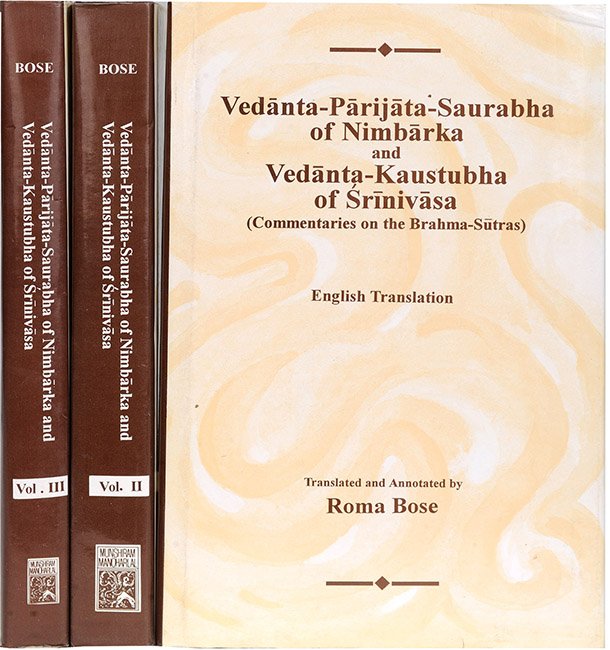

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 1.3.28, including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 1.3.28

English of translation of Brahmasutra 1.3.28 by Roma Bose:

“If it be objected that (a contradiction will result) with regard to word, (we reply:) no, on account of the origin (of everything) from it, on account of perception (i.e. scripture) and inference (i.e. Smṛti).”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

If it be objected that if the corporality of the gods be admitted, a contradiction will result with regard to the Vedic words denoting them, as these words will become meaningless prior to the origin of the objects (viz. the gods) denoted by them and subsequent to their destruction,—

(We reply:) No such contradiction results, “on account of the origin” of the objects (viz. the gods and the rest) “from it”, i.e. from the words alone, denoting eternal prototypes or forms, and serving as reminders to the thought of Prajāpati, in accordance with the following scriptural and Smṛti texts: ‘He evolved name and form by means of the Veda’ (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 2.6.2.3[1]),‘A celestial word, without beginning and end, eternal, and composed of the Vedas was omitted by the self-born in the beginning, whence proceeded all activities’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.8534[2]).

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Here, the word ‘contradiction’ is to be supplied from the preceding aphorism. If it be objected: Very well, there may not be any contradiction with regard to works if the gods he possessed of bodies, still there may be contradiction “with regard to the words” denoting gods and the rest, i.e. with regard to the Vedic forms. That is, on account of the non-eternity of the bodies of the gods,—they being due to karmas—as well as on account of the eternity of the Vedic texts, the eternal relation between a word and its meaning will be impossible, and hence a contradiction will result between the object which is limited in time and the word which is true for all times. If it be said that owing to the force of the word, the object too is eternal,—then a contradiction will result with regard to the texts which prove its non-eternity: if it be said that for the sake of the object, the word is non-eternal,—then there will arise a contradiction with regard to the texts which prove its eternity.—

(We reply:) “No”. There is no contradiction with regard to the word as well. Why? “On account of the origin from it”, i.e. on account of the origin, or the rise, of the gods and the rest from this, i.e from the Vedic words, denoting the eternal prototypes of gods, etc. and serving as a reminder to the thought of the creator regarding the forms of gods, etc. to be created at the time of each particular creation. Thus, when a certain great personality, who has accumulated a mass of merit and desires to become Prajāpati, comes to attain lordship through the grace of the Lord, he is called ‘Prajāpati’. At the time of creation when individuals like the former gods and the rest are no more, Prajāpati, having learnt the Veda in a manner to be designated hereafter,[3] and having apprehended, like a man arisen from sleep,[4] the particular prototypes of the gods and the rest by means of the lamp-like Veda, i.e. from the Vedic words alone which denote those particular prototypes, creates the later gods, etc. in accordance with those prototypes. Hence there is no room for the alleged contradiction.

If it be objected: What proof is there that Prajāpati creates objects after having known their particular forms from the Vedic words?—we reply: “On account of perception and inference”. “Perception” means Scripture, since it is independent of any other proof. “Inference” means Smṛti, since it demonstrates the meaning of Scripture,—on account of these two, i.e. on account of Scripture and Smṛti. First, the scriptural passage is the following; viz.: ‘Prajāpati evolved name[5] and form the existent and the non-existent, by means of the Veda’ (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 2.6.2.3), likewise: ‘He uttered “bhūr”, he created the earth’ (Taittirīya-upaniṣad 2.2.4.2[6]), ‘He uttered “bhuva”, he created the ether’ (Taittirīya-brāhmaṇa 2.2.4.2-3[7]) and so on. The Smṛti passage is contained in the Mokṣadharma[8], and beginning: ‘The sages read the Vedas day and night by penance’ (Mahābhārata (Asiatic Society edition) 12.85336b[9]), continues: ‘A celestial word, without beginning and end, eternal and composed of the Vedas, was emitted by the self-born in the beginning, whence proceeded all activities.[10] The Lord created the names of the sages and the creations which are in the Vedas, as well as the various forms of beings and the procedure of acts, from the Vedic words alone in the beginning. At the end of the night, the Unborn One bestowed the names of sages and the creations which are in the Vedas to others. The things that are celebrated in the world, namely, difference of names, austerity, work and sacrifice’.[11]

Similarly, there are other passages, viz. ‘In the beginning the Supreme Lord created the names and forms of beings, as well as the procedures of actions, from the Vedic word alone’[12] (Viṣṇu-purāṇa 1.5.62), ‘In the beginning, he created the names and actions of all as separate, as well as the different established orders,[13] from the Vedic word alone’ (Manu-saṃhitā 1.21[14]) and so on.[15]

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

[3]:

Vide Brahma-sūtra 1.3.30.

[4]:

That is, when a man arises from sleep at night he can see nothing until he lights a lamp. Similarly, at the beginning of creation, the creator knows particular objects from the lamp-like light of the Veda, i.e. knows the forms of those objects and creates them anew accordingly.

[6]:

P. 195, lines 7-8, vol. 2.

[7]:

Op. cit. lines 9-10.

[8]:

See footnote 1, p. 182.

[9]:

P. 663, line 22, vol. 3.

[10]:

For correct quotation, see footnote 2, p. 183.

[11]:

P. 666, lines 23-26, vol. 3.

Reading: ‘Nama rūpañ ca bhūtānāṃ karmāṇāñ ca pravartayan.....śārvaryy-ante sujātānām....’

Vaṅgavāsī ed. reads: ‘....pravartanam....sujātānām’. P. 1635, vol. 2.

[13]:

Cf. Kulluka-bhaṭṭa’s Commentary on the Manu-Smṛti (p. 10): ‘Pṛthak-saṃsthāś ca iti. Laukikīś ca vyavasthāḥ, kulālasya ghaṭa-nirmāṇam, kuvindasya paṭa-nirmāṇam ityādika-vibhāgena nirmitavān.’

[14]:

P. 9.

[15]:

The sum and substance of the argument is as follows: The prima facie view is that if the gods be possessed of bodies, then, since these bodies, are non-eternal, the gods must be so. But the Vedic words which denote the gods are eternal. Hence there cannot be any eternal connection between the non-etemal gods and the eternal Vedic words, i.e. these Vedic words cannot denote gods and the rest, and must be meaningless.

The answer to this objection is as follows: The individual gods are indeed non-eternal, but this does not prove that the eternal Vedic words are meaningless, for what they denote is not the individual (vyakti) which is non-etemal, but the type (ākṛti) which is eternal. It is in accordance with these eternal types, denoted by the eternal Vedic words, that the non-eternal individuals are created anew at the beginning of each creation.