Pravrittivishaya, Pravṛttiviṣaya, Pravritti-vishaya: 5 definitions

Introduction:

Pravrittivishaya means something in Buddhism, Pali, Hinduism, Sanskrit. If you want to know the exact meaning, history, etymology or English translation of this term then check out the descriptions on this page. Add your comment or reference to a book if you want to contribute to this summary article.

The Sanskrit term Pravṛttiviṣaya can be transliterated into English as Pravrttivisaya or Pravrittivishaya, using the IAST transliteration scheme (?).

In Hinduism

Shaivism (Shaiva philosophy)

Source: Brill: Śaivism and the Tantric Traditions (philosophy)Pravṛttiviṣaya (प्रवृत्तिविषय) refers to the “object upon which human activity may be exerted” [?], according to the Utpaladeva’s Vivṛti on Īśvarapratyabhijñākārikā 1.5.8-9.—Accordingly, “[...] And this mere [realization that the object is something separated from the subject] is not enough to transform this object into something on which [human] activity may be exerted (pravṛttiviṣaya); therefore [this object] is [also] made manifest as having a specific place and time, because only a particular having a specific place and time can be something on which [human] activity may be exerted, since [only such a particular] can be obtained and since [only such a particular] may have the efficacy that [we] expect [from it]. [...]”.

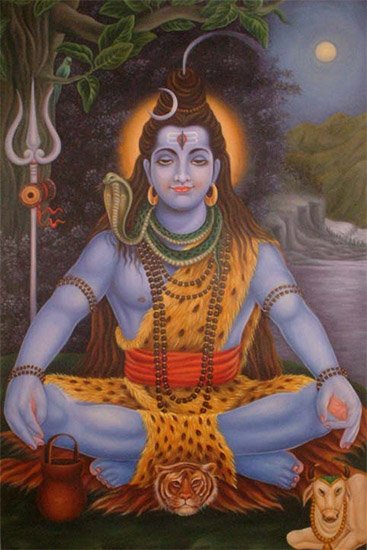

Shaiva (शैव, śaiva) or Shaivism (śaivism) represents a tradition of Hinduism worshiping Shiva as the supreme being. Closely related to Shaktism, Shaiva literature includes a range of scriptures, including Tantras, while the root of this tradition may be traced back to the ancient Vedas.

In Buddhism

Buddhist philosophy

Source: Google Books: Santaraksita and Kamalasila on Rationality, Argumentation, and Religious AuthorityPravṛttiviṣaya (प्रवृत्तिविषय) refers to the “object of one’s action”, according to Kamalaśīla.—Accordingly, “[Dealing with the question of the trustworthiness of perception]:—That is, inasmuch as it causes the person who desires a [particular] causal function to obtain the desired thing, (perception] is called a means of trustworthy awareness. But it does not make one attain [the desired causal function] by transporting the person to the place where the thing exists, nor by leading the thing to the place where the person exists. Instead, it causes the person to act. Nor does it cause the person to act by taking him by the hand. Rather, [it causes him to act] by revealing to him the object of his action (pravṛttiviṣaya). And that revelation comes about through the determination (avasāya) of the thing that is appearing [in the perceptual awareness] and not otherwise”.

Source: Google Books: The Treasury of Knowledge: Book six, parts one and two (philosophy)Pravṛttiviṣaya (प्रवृत्तिविषय) or simply Pravṛtti (Sanskrit; in Tibetan: ’jug yul) refers to “engaged objects”, representing one of the three types of “objects” (viṣaya) (i.e., ‘that which is to be comprehended or known’).—Accordingly, “That which is to be understood through valid cognition is ‘the knowable’. The terms ‘object’ (viṣaya; yul), ‘knowable’ (jñeya; shes bya), and ‘appraisable’ (prameya; gzhal bya) are all essentially equivalent, but it is the defining characteristic of the ‘object’ that it is to be comprehended or known, [...]. When objects (viṣaya) are analyzed in terms of their different functionalities as objects (yul du byed tshul), they fall into three distinct categories, namely, [i.e., applied or engaged objects (pravṛttiviṣaya—’jug yul),] [...]

Source: Google Books: Essays on Dharmakirti and his Tibetan SuccessorsPravṛttiviṣaya (प्रवृत्तिविषय) refers to the “object of practical application”, according to Dharmottara’s Nyāyabinduṭīkā (commentary on Dharmakīrti's Nyāyabindu).—Accordingly, “[...] Similarly, inference does not apprehend the [actual] object either (anarthagrāhin), in that it practically applies by determining its own representation, which is not the [actual] object, to be the object. Still, because the imagined object which is being apprehended is determined to be a particular, the determined particular is therefore the object of practical application (pravṛttiviṣaya) of inference, but what is apprehended [by conceptual thought] is not the [actual] object”.

Source: Wisdom Experience: Mind (An excerpt from Science and Philosophy)Pravṛttiviṣaya (प्रवृत्तिविषय) refers to the “engaged object (of one’s action)”, according to the Dalai Lama’s “Science and Philosophy in the Indian Buddhist Classics”.—The notion that conceptual cognitions are necessarily mistaken—even when they are epistemically reliable—reflects an overall suspicion of conceptuality that characterizes Indian Buddhism from its earliest days, but the technical account in part 1 draws especially on Dharmakīrti and other Buddhist epistemologists. For these theorists, conceptual cognitions are always mistaken in two ways. First, the object that appears phenomenally in my awareness, known as the conceptual “image” (pratibimba) of the object, is taken to be identical to the functional thing that I seek to act upon as the engaged object (pravṛttiviṣaya) of my action. In other words, the phenomenally presented object “fire” in my conceptual cognition does not have the causal properties of an actual fire—the thought of a fire cannot burn wood. Yet our cognitive system creates a fusion (ekīkaraṇa) of this phenomenal appearance with the engaged object to which the conceptual image of “fire” refers.

-

See also (Relevant definitions)

Partial matches: Vishaya, Pravritti, Vicaya.

Full-text: Pravritti, Vishaya, Ekikarana, Avasaya, Pratibimba.

Relevant text

No search results for Pravrittivishaya, Pravṛttiviṣaya, Pravṛtti-viṣaya, Pravritti-vishaya, Pravrttivisaya, Pravrtti-visaya; (plurals include: Pravrittivishayas, Pravṛttiviṣayas, viṣayas, vishayas, Pravrttivisayas, visayas) in any book or story.