Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

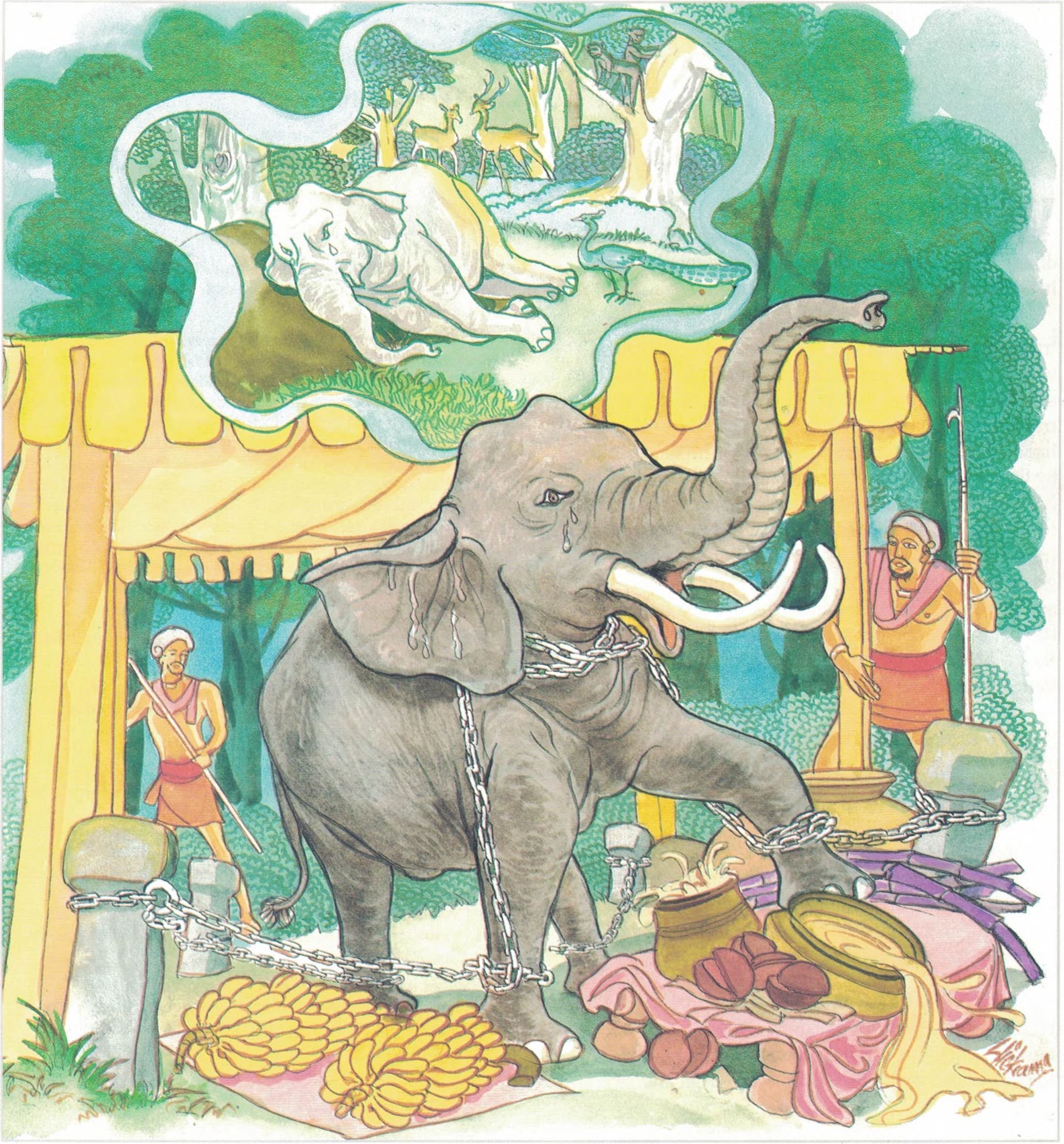

This page describes The Story of an Old Brahmin which is verse 324 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 324 is part of the Nāga Vagga (The Great) and the moral of the story is “The elephant in rut, hardly restrainable, eats not in captivity, remembering its forest life”.

Verse 324 - The Story of an Old Brāhmin

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 324:

dhanapālako nāma kuñjaro kaṭukappabhedano dunnivārayo |

baddho kabalaṃ na bhuñjati sumarati nāgavanassa kuñjaro || 324 ||

324. Hard to check the tusker Dhanapālaka, in rut with temples running pungently, bound, e’en a morsel he’ll not eat for he recalls the elephant-forest longingly.

The elephant in rut, hardly restrainable, eats not in captivity, remembering its forest life. |

The Story of an Old Brāhmin

While residing at the Veluvana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to an old brāhmin.

Once, there lived in Sāvatthi an old brāhmin who had eight lakhs in cash. He had four sons; when each one of the sons got married, he gave one lakh to him. Thus, he gave away four lakhs. Later, his wife died. His sons came to him and looked after him very well; in fact, they were very loving and affectionate to him. In course of time, somehow they coaxed him to give them the remaining four lakhs. Thus, he was left practically penniless.

First, he went to stay with his eldest son. After a few days, the daughter-in-law said to him, “Did you give any extra hundred or thousand to your eldest son? Don’t you know the way to the houses of your other sons? Hearing this, the old brāhmin got very angry and he left the eldest son’s house for the house of his second son. The same thing happened in the houses of all his sons. Thus, the old man became helpless; then, taking a staff and a bowl he went to the Buddha for protection and advice.

At the monastery, the brāhmin told the Buddha how his sons had treated him and asked for his help. Then the Buddha gave him some verses to memorize and instructed him to recite them wherever there was a large gathering of people. The gist of the verses is this: “My four foolish sons are like ogres. They call me ‘father, father’, but the words come only out of their mouths and not from their hearts. They are deceitful and scheming. Taking the advice of their wives they have driven me out of their houses. So, now I have got to be begging. Those sons of mine are of less service to me than this staff of mine.” When the old brāhmin recited these verses, many people in the crowd, hearing him, went wild with rage at his sons and some even threatened to kill them.

At this, the sons became frightened and knelt down at the feet of their father and asked for pardon. They also promised that starting from that day they would look after their father properly and would respect, love and honour him. Then, they took their father to their houses; they also warned their wives to look after their father well or else they would be beaten to death. Each of the sons gave a length of cloth and sent every day a food-tray. The brāhmin became healthier than before and soon put on some weight. He realized that he had been showered with these benefits on account of the Buddha. So, he went to the Buddha and humbly requested him to accept two foodtrays out of the four he was receiving every day from his sons. Then he instructed his sons to send two food-trays to the Buddha.

One day, the eldest son invited the Buddha to his house for alms-food. After the meal, the Buddha gave a discourse on the benefits to be gained by looking after one’s parents. Then he related to them the story of the elephant called Dhanapāla, who looked after his parents. Dhanapāla when captured pined for the parents who were left in the forest.

At the end of the discourse, the old Brāhmin as well as his four sons and their wives attained sotāpatti fruition.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 324)

dhanapālako nāma kuñjaro kaṭūkappabhedana dunnivārayo

baddho kabalaṃ na bhuñjati kuñjaro nāgavanassa sumarati

dhanapālako nāma: named Dhanapāla; kabalaṃ [kabala]: food; na bhuñjati: does not eat;kuñjaro [kuñjara]: elephant; kaṭūkappabhedana: deep in rut; dunnivārayo [dunnivāraya]: difficult to be restrained; baddho [baddha]: shackled; nāga vanassa: the elephant–forest; sumarati: keeps on longing for

The elephant, Dhanapāla, deep in rut and uncontrollable, in captivity did not eat a morsel as he yearned for his native forest (i.e., longing to look after his parents).

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 324)

This stanza and the story that gave rise to it, have a marked validity for our own time when the neglect of the aged has become a crucial social issue.