Dhammapada (Illustrated)

by Ven. Weagoda Sarada Maha Thero | 1993 | 341,201 words | ISBN-10: 9810049382 | ISBN-13: 9789810049386

This page describes The Story of Schism in the Sangha which is verse 163 of the English translation of the Dhammapada which forms a part of the Sutta Pitaka of the Buddhist canon of literature. Presenting the fundamental basics of the Buddhist way of life, the Dhammapada is a collection of 423 stanzas. This verse 163 is part of the Atta Vagga (Self) and the moral of the story is “Calamitous, self-ruinous things are easy to do. Beneficial and worthy are most difficult to do”.

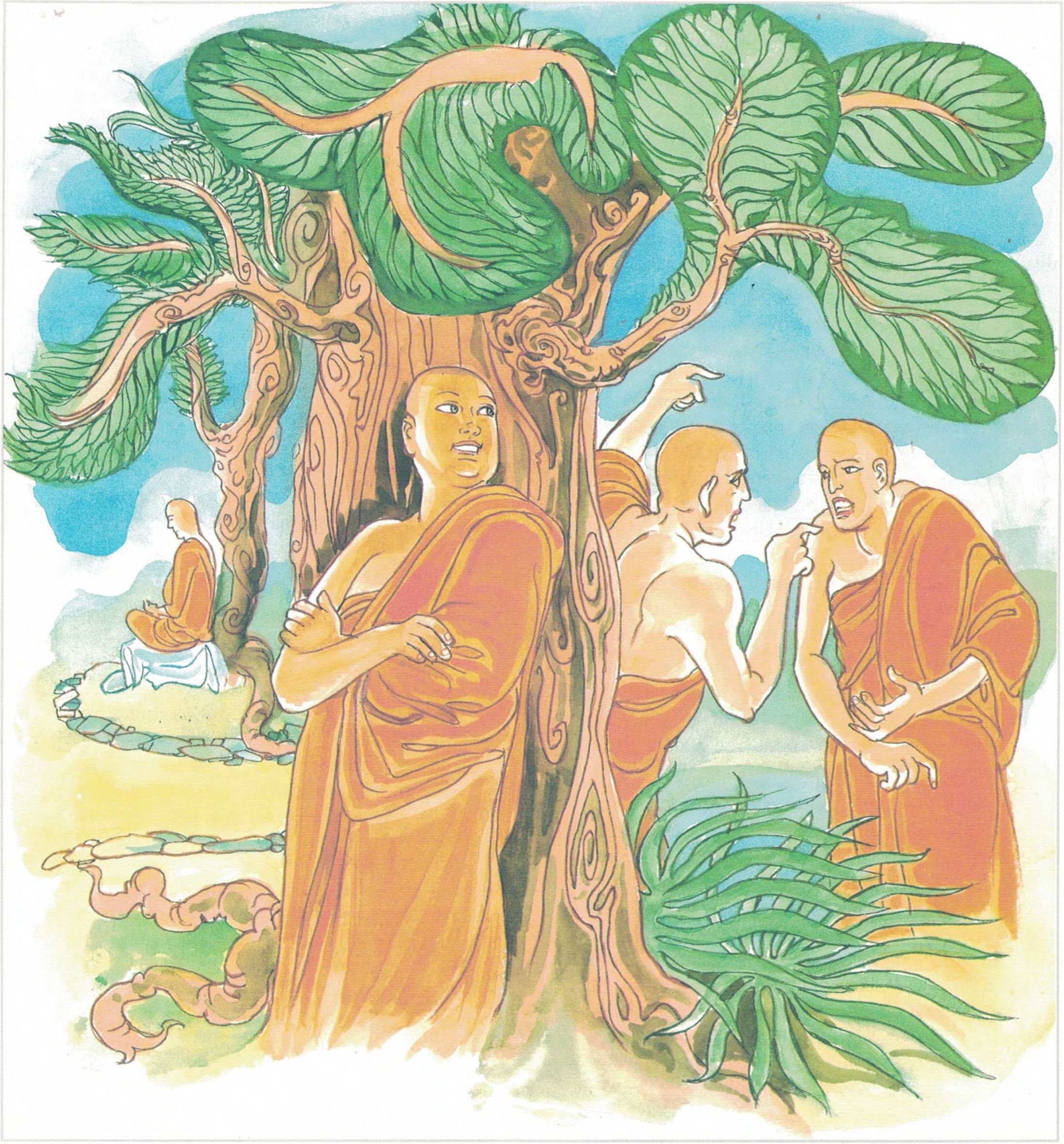

Verse 163 - The Story of Schism in the Sangha

Pali text, illustration and English translation of Dhammapada verse 163:

sukarāni asādhūni attano ahitāni ca |

yaṃ ve hitañca sādhuṃ ca taṃ ve paramadukkaraṃ || 163 ||

163. Easy is what’s bad to do what’s harmful to oneself. But what is good, of benefit, is very hard to do.

Calamitous, self-ruinous things are easy to do. Beneficial and worthy are most difficult to do. |

The Story of Schism in the Sangha

While residing at the Veluvana Monastery, the Buddha spoke this verse, with reference to Devadatta, who committed the offence of causing a schism in the Sangha of the monks.

On one occasion, while the Buddha was giving a discourse in the Veluvana Monastery, Devadatta came to him and suggested that since the Buddha was getting old, the duties of the sangha should be entrusted to him (Devadatta); but the Buddha rejected his proposal and also rebuked him and called him a spittle swallower (Khelasika). From that time, Devadatta felt very bitter towards the Buddha. He even tried to kill the Buddha three times, but all his attempts failed. Later, Devadatta tried another tactic. This time, he came to the Buddha and proposed five rules of discipline for the monks to observe throughout their lives. He proposed (i) that the monks should live in the forest; (ii) that they should live only on food received on alms-rounds; (iii) that they should wear robes made only from pieces of cloth collected from rubbish heaps; (iv) that they should reside under trees; and (v) that they should not take fish or meat. The Buddha did not have any objections to these rules and made no objections to those who were willing to observe them, but for various valid considerations, he was not prepared to impose these rules of discipline on the monks in general.

Devadatta claimed that the rules proposed by him were much better than the existing rules of discipline, and some new monks agreed with him. One day, the Buddha asked Devadatta if it was true that he was trying to create a schism in the order, and he admitted that it was so. The Buddha warned him that it was a very serious offence, but Devadatta paid no heed to his warning. After this, as he met Venerable Ānanda on his almsround in Rājagaha, Devadatta said to Venerable Ānanda, “Ānanda, from today I will observe the sabbath (Uposatha), and perform the duties of the order separately independent of the Buddha and his order of monks.” On his return from the alms-round, Venerable Ānanda reported to the Buddha what Devadatta had said.

On hearing this, the Buddha reflected, “Devadatta is committing a very serious offence; it will send him to Avīci Niraya. For a virtuous person, it is easy to do good deeds and difficult to do evil; but for an evil one, it is easy to do evil and difficult to do good deeds. Indeed, in life it is easy to do something which is not beneficial, but it is very difficult to do something which is good and beneficial.” Then on the Uposatha day, Devadatta followed by five hundred Vajjian monks, broke off from the order, and went to Gayāsīsa. However, when the two chief disciples, Sāriputta and Moggallāna, went to see the monks who had followed Devadatta and talked to them they realized their mistakes and most of them returned with the two chief disciples to the Buddha.

Explanatory Translation (Verse 163)

asādhūni attano ahitāni ca sukarāni yaṃ ve

hitañca sādhuñ ca taṃ ve parama dukkaraṃ

asādhūni: bad actions; attano ahitāni ca: actions that are harmful to oneself; sukarāni: are easy to be done; yaṃ: if something; ve hitañca: is indeed good to one’s self; sādhuñ ca: if it is also right; taṃ: that kind of action; ve: (is) certainly; parama dukkaraṃ [dukkara]: extremely difficult to do

Those actions which are bad and harmful to one’s own self can be very easily done. But if some action is good for one’s own self; if it is also right, certainly that kind of action will be found to be extremely difficult to do.

Commentary and exegetical material (Verse 163)

attano ahitāni sukarāni: actions that are harmful to oneself are easy to be done. This was stated with reference to the schism Devadatta committed. Though absolutely pure in motive and perfectly selfless in His service to humanity, yet, in preaching and spreading His teaching, the Buddha had to contend against strong opposition. He was severely criticized, roundly abused, insulted and ruthlessly attacked, as no other religious teacher had been. His chief opponents were teachers of rival sects and followers of heretical schools, whose traditional teachings and superstitious rites and ceremonies he justly criticized. His greatest personal enemy, who made a vain attempt to kill Him, was His own brother-in-law and an erstwhile disciple Devadatta. Devadatta was the son of King Suppabuddha and Pamitā, an aunt of the Buddha. Yasodharā was his sister. He was thus a cousin and brother-in-law of the Buddha. He entered the sangha in the early part of the Buddha’s ministry together with Ānanda and other Sākyan princes. He could not attain any of the stages of Sainthood, but was distinguished for worldly psychic powers (pothujjanika-iddhi). One of his chief supporters was King Ajātasattu who built a monastery for him.