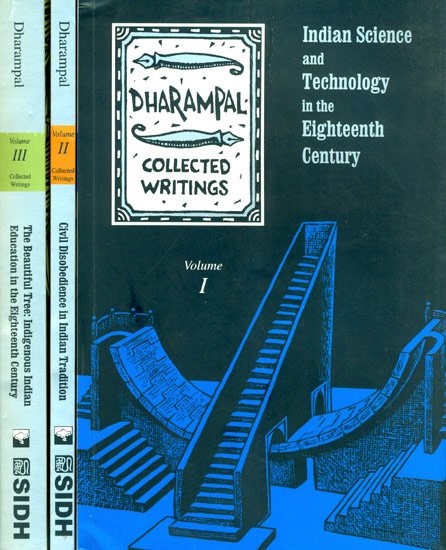

Dharampal Collected Writings

author: Dharampal

edition: 2016, Other India BookStore

pages: 1835

ISBN-10: 8185569509

ISBN-13: 9788185569505

Topic: History

Volume 4: Preface

After its publication at the end of 1957 much excitement and expectation was aroused from the report of the Committee on Plan Projects more popularly known as the report of the Balwantray Mehta Committee. The Committee urged that the state rural development programmes be managed by statutorily elected bodies at various levels: the village the community development block and the district; and termed the arrangement 'panchayat raj', Within months these bodies began to be created through laws enacted in each state of India. The administration of development under the management of these bodies started with Rajasthan in early 1959.

Within a year or two of this beginning interested groups began to explore what was happening under this arrangement. Many studies of this new programme got undertaken by 1960 or 1961. The Association of Voluntary Agencies for Rural Development (AVARD). Delhi was also seriously interested in what was happening and took up on-the-spot studies of the programme. first in Rajasthan and next in Andhra Pradesh. From this AVARD moved on to a study of the proceedings of India's Constituent Assembly during 1947-49 on the subject of the place of panchayats in India's polity. The full debate on the subject was put together by AVARD in early 1962 published under the title Panchayat Raj as the Basis o Indian Polity: An Exploration into the Proceedings of the Constituent Assembly. The publication opened up a somewhat forgotten chapter on the subject and aroused much discussion and interest. The idea of this exploration was initially suggested by my friend. L.C. Jain.

The earlier AVARD studies and Panchayat Raj as the Basis of Indian Polity led to the suggestion that post-1958 panchayat raj programmes should be studied in greater depth. This view was also shared by the then central Ministry of Community Development and Panchayati Raj as well as by the National Institute of Community Development. It was also then felt that the most appropriate body to undertake this study would be the All India Panchayat Parishad (AlPP). After various consultations it was decided by the end of 1963 that the first such study should be of the panchayat system in Madras state i.e in Tamilnadu. The Rural Development and Local Administration (RDLA) Department of Tamilnadu welcomed the idea of the study and extended all possible cooperation and support to it. The Additional Development Commissioner of Tamilnadu. Sri G. Venkatachellapaty took personal interest in the study and arranged matters in a way that the AIPP study team had access to most of the records of the RDLA Department up to 1964. The study also had the advice and guidance of Sri K. Raja Ram. President of the Tamilnadu Panchayat Union and of Prof R. Bhaskaran, Head of the Political Science Department of Madras University. Sri S.R. Subramaniam of the Tamilnadu Sarvodaya Mandal, a prominent public figure of Madras was also of great help. The study also had the continued support of the National Institute of Community Development and of its Director and scholars.

The study got underway in early 1964 and ended in December 1965. The Madras Panchayat System was written during the latter half of the year 1965 and some final touches were given to it in January 1966. The material on late 18th and early 19th century India and the policies adopted by the British at that time, referred to in Chapter V: The Problem, was also examined during 1964-1965 in the Tamilnadu State Archives. As the present author had occasion to be in London during August-October 1965, he also had an opportunity to peruse some additional circa 1800 material at the India Office Library and the British Library, London.

This study, done during 1964-1965 would appear dated today. The post-1958 panchayat institutions constituted on the recommendations of the Balwantrai Mehta Committee Report, assumed a low profile after 1965. Ultimately they began to decay more or less in the same manner as these institutions had done several times after they began to be established by the British in the 1880s. However during the last decade or so new panchayat institutions are being created with much larger claimed participation of women and members from the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and with far larger resources even in terms of proportion of state government budgets, than those allotted to them in the 1920s. Despite all the claimed changes, it is possible that the new institutions have not acquired any more initiative, or control over their resources, or over what they do-than their predecessors after about 1925.

Regarding the late 18th and early 19th century background (briefly referred to in Chapter V), there is a vast amount of material relating to this in the British records .of the period for most parts of India. Some indications of how Indian society actually functioned before it came under British dominance, and how it began to get impoverished and its institutions fell into decay because of British policies, are provided, amongst others, in some of the work I have been able to do after this study on the Madras Panchayat System. A detailed study based on circa 1770 palm-leaf records in Tamil, now held in the Tamil University, Thanjavur, (partial versions of them are in the Tamilnadu State Archives) relating to the complex institutional structure, details of agricultural productivity, the caste-wise and occupational composition of each and every locality, and other details of over 2000 villages and towns of the then Chengalpattu district is at present going on at the Centre for Policy Studies, Chennai. These studies, when completed, should enable us to gain more knowledge about our society and its self-governing institutions and system before the era of British domination.