Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

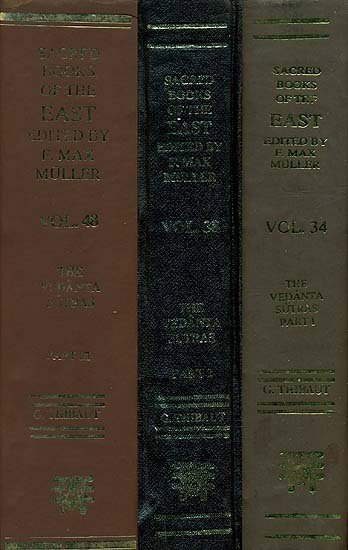

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 4.4.7

7. Thus also, on account of existence of the former qualities (as proved) by suggestion, Bādarayaṇa holds absence of contradiction.

The teacher Bādarāyaṇa is of opinion that even thus, i.e. although the text declares the soul to have mere intelligence for its essential nature, all the same the previously stated attributes, viz. freedom from all sin, and so on, are not to be excluded. For the authority of a definite statement in the Upanishads proves them to exist ('That Self which is free fiom sin,' etc.); and of authorities of equal strength one cannot refute the other. Nor must you say that the case is one of essential contradiction, and that hence we necessarily must conclude that freedom from sin, and so on (do not belong to the true nature of the soul, but) are the mere figments of Nescience (from which the released soul is free). For as there is equal authority for both sides, why should the contrary view not be held? (viz. that the soul is essentially free from sin, etc., and that the caitanya is non-essential.) For the principle is that where two statements rest on equal authority, that only which suffers from an intrinsic impossibility is to be interpreted in a different way (i.e. different from what it means on the face of it), so as not to conflict with the other. But while admitting this we deny that the text which describes the Self as a mass of mere knowledge implies that the nature of the Self comprises nothing whatever but knowledge.—But what then is the purport of that text?—The meaning is clear, we reply; the text teaches that the entire Self, different from all that is non-sentient, is self-illumined, i.e. not even a small part of it depends for its illumination on something else. The fact, vouched for in this text, of the soul in its entirety being a mere mass of knowledge in no way conflicts with the fact, vouched for by other texts, of its possessing qualities such as freedom from sin and so on, which inhere in it as the subject of those qualities; not any more than the fact of the lump of salt being taste through and through—which fact is known through the sense of taste—conflicts with the fact of its possessing such other qualities as colour, hardness, and so on, which are known through the eye and the other sense-organs. The meaning of the entire text is as follows—just as the lump of salt has throughout one and the same taste, while other sapid things such as mangoes and other fruit have different tastes in their different parts, rind and so on; so the soul is throughout of the nature of knowledge or self-illuminedness.—Here terminates the adhikaraṇa of 'that which is like Brahman.'