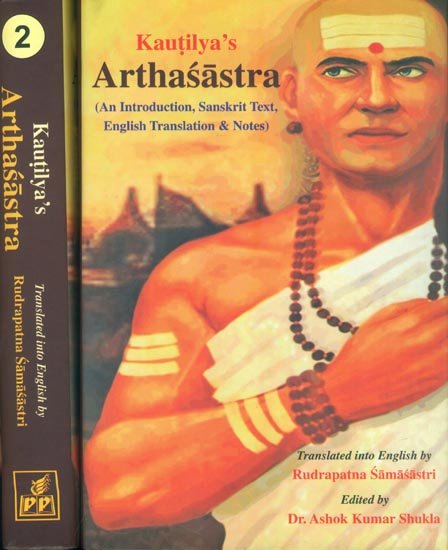

Kautilya Arthashastra

by R. Shamasastry | 1956 | 174,809 words | ISBN-13: 9788171106417

The English translation of Arthashastra, which ascribes itself to the famous Brahman Kautilya (also named Vishnugupta and Chanakya) and dates from the period 321-296 B.C. The topics of the text include internal and foreign affairs, civil, military, commercial, fiscal, judicial, tables of weights, measures of length and divisions of time. Original ...

Chapter 13 - Considerations about an Enemy in the Rear

[Sanskrit text for this chapter is available]

When the conqueror and his enemy simultaneously proceed to capture the rear of their respective enemies who are engaged in an attack against others, he who captures the rear of one who is possessed of vast resources gains more advantage (atisandhatte); for one who is possessed of vast resources has to put down the rear-enemy only after doing away with one’s frontal enemy already attacked, but not one who is poor in resources and who has not realised the desired profits.

Resources being equal, he who captures the rear of one who has made vast preparations gains more advantages, for one who has made vast preparations has to put down the enemy in the rear only after destroying the frontal enemy, but not one whose preparations are made on a small scale and whose movements are, therefore, obstructed by the Circle of States.

Preparations being equal, he who captures the rear of one who has marched out with all the resources gains more advantages; for one whose base is undefended is easy to be subdued, but not one who has marched out with a part of the army after having made arrangements to defend the rear.

Troops taken being of equal strength, he who captures the rear of one who has gone against a wandering enemy gains more advantages: for one who has marched out against a wandering enemy has to put down the rear-enemy only after obtaining an easy victory over the wandering enemy; but not one who has marched out against an entrenched enemy, for one who has marched out against the entrenched enemy will be repelled in his attack against the enemy’s forts and will, after his return, find himself between the rear-enemy and the frontal enemy who is possessed of strong forts.

This explains the cases of other enemies described before.[1]

Enemies being of equal description, he who attacks the rear of one who has gone against a virtuous king gains more advantages, for one who has gone against a virtuous king will incur the displeasure of even his own people, whereas one who has attacked a wicked king will endear himself to all.

This explains the consequences of capturing the rear of those who have marched against an extravagant king, or a king living from hand to mouth, or a niggardly king.

The same reasons hold good in the case of those who have marched against their own friends.

When there are two enemies, one engaged in attacking a friend and another an enemy, he who attacks the rear of the latter gains more advantages: for one who has attacked a friend will, after easily making peace with the friend, proceed against the rear-enemy; for it is easier to make peace with a friend than with an enemy.

When there are two kings, one engaged in destroying a friend and another an enemy, he who attacks the rear of the former gains more advantages; for one who is engaged in destroying an enemy will have the support of his friends and will thereby put down the rear-enemy, but not the former who is engaged in destroying his own side.

When the conqueror and his enemy in their attack against the rear of an enemy mean to enforce the payment of what is not due to them, he whose enemy has lost considerable profits and has sustained a great loss of men and money gains more advantages: when they mean to enforce the payment of what is due to them, then he whose enemy has lost profits and army, gains more advantages.

When the assailable enemy is capable of retaliation and when the assailant’s rear-enemy, capable of augmenting his army and other resources, has entrenched himself on one of the assailant’s flanks, then the rear-enemy gains more advantages; for a rear enemy on one of the assailant’s flanks will not only become a friend of the assailable enemy, but also attack the base of the assailant whereas a rear-enemy behind the assailant can only harass the rear.

* Kings capable of harassing the rear of an enemy and of obstructing his movements are three: the group of kings situated behind the enemy, and the groups of kings on his two flanks.

* He who is situated between a conqueror and his enemy is called an antardhi (one between two kings); when such a king is possessed of forts, wild tribes, and other kinds of help, he proves an impediment in the way of the strong.

When the conqueror and his enemy are desirous of catching hold of a Madhyama king and attack the latter’s rear, then he who in his attempt to enforce the promised payment separates the Madhyama king from the latter’s friend, and obtains, thereby, an enemy as a friend, gains more advantages; for an enemy compelled to sue for peace will be of greater help than a friend compelled to maintain the abandoned friendship.

This explains the attempt to catch hold of a neutral king.

Of attacks from the rear and front, that which affords opportunities of carrying on a treacherous fight (mantrayuddha) is preferable.

My teacher says that in an open war, both sides suffer fay sustaining a heavy loss of men and money; and that even the king who wins a victory will appear as defeated in consequence of the loss of men and money.

* No, says Kauṭilya, even at considerable loss of men and money, the destruction of an enemy is desirable.

Loss of men and money being equal, he who entirely destroys first his frontal enemy, and next attacks his rear-enemy gains more advantages; when both the conqueror and his enemy are severally engaged in destroying their respective frontal enemies, he who destroys a frontal enemy of deep-rooted enmity and of vast resources, gains more advantages.

This explains the destruction of other enemies and wild tribes:

* When an enemy in the rear and in the front, and an assailable enemy to be marched against happen together, then the conqueror should adopt the following policy:

* The rear-enemy will usually lead the conqueror’s frontal enemy to attack the conqueror’s friend; then having set the ākranda (the enemy of the rear-enemy) against the rear-enemy’s ally.

* And, having caused war between them, the conqueror should frustrate the rear-enemy’s designs; likewise he should provoke hostilities between the allies of the ākranda and of the rear-enemy;

* he should also keep his frontal enemy’s friend engaged in war with his own friend; and with the help of his friend’s friend he should avert the attack, threatened by the friend of his enemy’s friend;

* he should, with his friend’s help, hold his rear-enemy at bay; and with the help of his friend’s friend he should prevent his rear-enemy attacking the ākranda (his rear-ally);

* thus the conqueror should, through the aid of his friends, bring the Circle of States under his own sway, both in his rear and front;

* he should send messengers and spies to reside in each of the states composing the Circle, and having again and again destroyed the strength of his enemies, he should keep his counsels concealed, being friendly with his friends;

* the works of him whose counsels are not kept concealed will, though they may prosper for a time, perish as undoubtedly as a broken raft on the sea.

[Thus ends Chapter XIII, “Considerations about an Enemy in the Rear,” in Book VII, “The End of the Six-fold Policy” of the Arthaśāstra of Kauṭilya. End of the hundred and eleventh chapter from the beginning.]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Mr. Meyer takes the word atisandhatte in this and other paragraphs in the sense of atisandhīyate and translates it, “hat den nach teil,” gets into disadvantage. He seems to think that the conqueror capturing the rear of rather a powerful than a weak enemy will himself be attacked by the powerful enemy and he will thus get into trouble. But in the view of the author the chief aim of the conqueror ought to be the seizing of the land in the rear of the enemy’s country, as clearly stated in the third paragraph. There he says that the rear of one who has marched with all his resources without provision for the defence of his rear is easily seized. A war on this account seems to have been considered as a remote contingency. Even if it happens, the conqueror is expected to rely upon the aid of his enemy, now in alliance with him. See Chapter IX, Book VII. Hence Meyer’s emendation is unnecessary and misleading.