Brahma Sutras (Ramanuja)

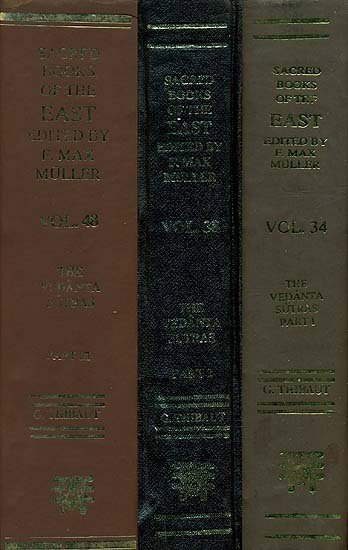

by George Thibaut | 1904 | 275,953 words | ISBN-10: 8120801350 | ISBN-13: 9788120801356

The English translation of the Brahma Sutras (also, Vedanta Sutras) with commentary by Ramanuja (known as the Sri Bhasya). The Brahmasutra expounds the essential philosophy of the Upanishads which, primarily revolving around the knowledge of Brahman and Atman, represents the foundation of Vedanta. Ramanjua’s interpretation of these sutras from a V...

Sutra 3.3.38

38. Wishes and the rest, here and there; (as is known from the abode, and so on).

We read in the Chāndogya (VIII, I, 1), 'There is that city of Brahman, and in it the palace, the small lotus, and in it that small ether,' etc.; and in the Vājasaneyaka, 'He is that great unborn Self who consists of knowledge,' and so on. A doubt here arises whether the two texts constitute one meditation or not.—The two meditations are separate, the Pūrvapakshin maintains; for they have different characters. The Chāndogya represents as the object of meditation the ether as distinguished by eight different attributes, viz. freedom from all evil and the rest; while, according to the Vājasaneyaka, the being to be meditated on is he who dwells within that ether, and is distinguished by attributes such as lordship, and so on.—To this we reply that the meditations are not distinct, since there is no difference of character. For desires and so on constitute that character 'here and there,' i.e. in both texts nothing else but Brahman distinguished by attributes, such as having true wishes, and so on, forms the subject of meditation. This is known 'from the abode and so on,' i.e. the meditation is recognised as the same because in both texts Brahman is referred to as abiding in the heart, being a bridge, and so on. Lordship and the rest, which are stated in the Vājasaneyaka, are special aspects of the quality of being capable to realise all one’s purposes, which is one of the eight qualities declared in the Chāndogya, and as such prove that all the attributes going together with that quality in the Chāndogya are valid for the Vājasaneyaka also. The character of the two vidyās therefore does not differ. The connexion with a reward also does not differ, for it consists in both cases in attaining to Brahman; cp. Kh. Up. VIII, 12,3 'Having approached the highest light he is manifested in his own form,' and Bṛ. Up. V, 4, 24 'He becomes indeed the fearless Brahman.' That, in the Chāndogya-text, the term ether denotes the highest Brahman, has already been determined under I, 3, 14. As in the Vājasaneyaka, on the other hand, he who abides in the ether is recognised as the highest Self, we infer that by the ether in which he abides must be understood the ether within the heart, which in the text 'within there is a little hollow space (sushira)' (Mahānār. Up. XI, 9) is called sushira. The two meditations are therefore one. Here an objection is raised. It cannot be maintained that the attributes mentioned in the Chāndogya have to be combined with those stated in the Vājasaneyaka (lordship, rulership, etc.), since even the latter are not truly valid for the meditation. For the immediately preceding passage, 'By the mind it is to be perceived that there is here no plurality: from death to death goes he who sees here any plurality; as one only is to be seen that eternal being, not to be proved by any means of proof,' as well as the subsequent text, 'that Self is to be described by No, no,' shows that the Brahman to be meditated upon is to be viewed as devoid of attributes; and from this we infer that the attributes of lordship and so on, no less than the qualities of grossness and the like, have to be denied of Brahman. From this again we infer that in the Chāndogya also the attributes of satyakāmatva and so on are not meant to be declared as Brahman’s true qualities. All such qualities—

as not being real qualities of Brahman—have therefore to be omitted in meditations aiming at final release.—This objection the next Sūtra disposes of.