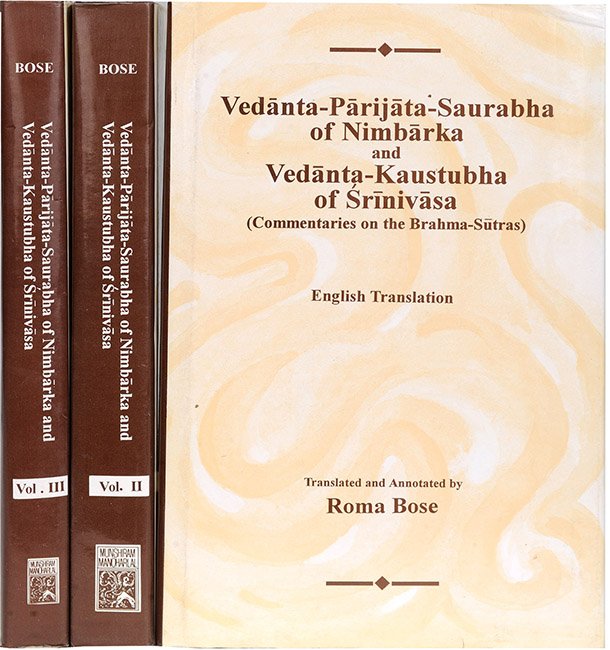

Brahma Sutras (Nimbarka commentary)

by Roma Bose | 1940 | 290,526 words

English translation of the Brahma-sutra 4.4.7 (correct conclusion), including the commentary of Nimbarka and sub-commentary of Srinivasa known as Vedanta-parijata-saurabha and Vedanta-kaustubha resepctively. Also included are the comparative views of important philosophies, viz., from Shankara, Ramanuja, Shrikantha, Bhaskara and Baladeva.

Brahma-Sūtra 4.4.7 (correct conclusion)

English of translation of Brahmasutra 4.4.7 by Roma Bose:

“Even so, on account or reference, on account of the existence of the former, non-contradiction, Bādarāyaṇa.”

Nimbārka’s commentary (Vedānta-pārijāta-saurabha):

Even if the real nature of the soul be established to be intelligence only, still owing to the manifestation of the real nature of the soul as possessed of freedom from sins and so on, there is “no contradiction”—so the reverend “Bādarāyaṇa” thinks. Why? “On account of the reference” to freedom from sins and so on as belonging to the freed soul.

Śrīnivāsa’s commentary (Vedānta-kaustubha)

Now, the reverend teacher of the Vedas states his own view in conformity with both the scriptural texts.

“Even so,” i.e. even if the soul be established to be mere intelligence, yet “on account of the existence of the former”, i.e. owing to the manifestation of the individual soul as intelligence by nature and as endowed with the attributes of freedom from sins and the rest, there is “no contradiction” with regard to the nature of salvation,—so the reverend “Bādarāyaṇa” thinks. Why? “On account of reference,” i.e. because in the declaration of Prajāpati,[1] freedom from sins and the rest, belonging to Brahman, are referred to as belonging to the freed soul as well. It cannot be said that in the text: “A mass of intelligence only” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.5.13), the word ‘only’ proves that the attributes of freedom from sins and so on do not belong to the soul, because they are clearly proved to be belonging to it by another text: “The self that is free from sins” (Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.7.1, 3) and so on, and because the word ‘only’ simply distinguishes the self from non-sentient objects,—just as it cannot be said that in the text: “A mass of taste only” (Bṛhadāraṇyaka-upaniṣad 4.5.13), the word ‘only’ proves that colour, touch and so on do not belong to salt, because they are known from other means of knowledge,[2] and because the word ‘only’ simply distinguishes salt from other objects. The purport is that Auḍulomi’s view, designating the freed soul as devoid of consciousness, is not acceptable. Hereby other logicians and the rest too, holding the freed soul to be devoid of consciousness, are refuted. Hence it is established that having attained the form of highest light, the individual soul becomes manifest in its own natural form as endowed with the attributes of freedom from sins and so on, conformably with both the scriptural texts.

Here ends the section entitled “Relating to Brahman” (3).

Comparative views of Śaṅkara:

He takes Jaimini to be representing the phenomenal point' of view, Auḍulomi the transcendental point of view, and Bādarāyaṇa as reconciling these two points of view.[3]

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Chāndogya-upaniṣad 8.7.1.

[2]:

Just as a lump of salt has not taste only, but has also colour and so on, so the soul is not intelligence only, but has other attributes also.

[3]:

Brahma-sūtras (Śaṅkara’s commentary) 4.4.7, p. 971.