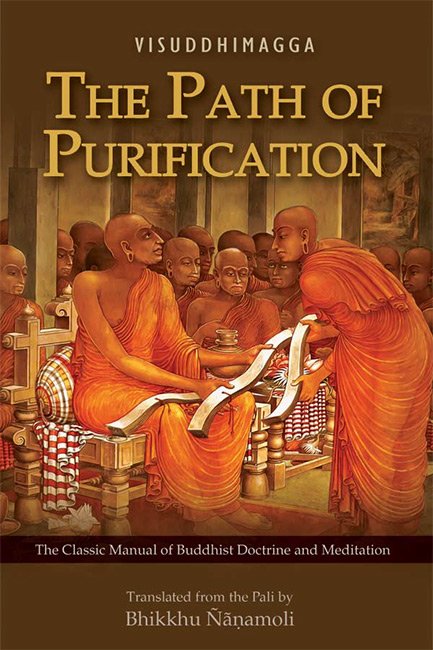

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes The Three Kinds of Full-understanding of the section Purification by Knowledge and Vision of the Path and the Not-path of Part 3 Understanding (Paññā) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

The Three Kinds of Full-understanding

3. Here is the exposition: there are three kinds of mundane full-understanding, that is, full-understanding as the known, full-understanding as investigation, and full-understanding as abandoning, with reference to which it was said: “Understanding that is direct-knowledge is knowledge in the sense of being known. Understanding that is full-understanding is knowledge in the sense of investigating. Understanding that is abandoning is knowledge in the sense of giving up” (Paṭis I 87).

Herein, the understanding that occurs by observing the specific characteristics of such and such states thus, “Materiality (rūpa) has the characteristic of being molested (ruppana);feeling has the characteristic of being felt,” is called fullunderstanding as the known. The understanding consisting in insight with the general characteristics as its object that occurs in attributing a general characteristic to those same states in the way beginning, “Materiality is impermanent, [607] feeling is impermanent” is called full-understanding as investigation.[1] The understanding consisting in insight with the characteristics as its object that occurs as the abandoning of the perception of permanence, etc., in those same states is called full-understanding as abandoning.

4. Herein, the plane of full-understanding as the known extends from the delimitation of formations (Ch. XVIII) up to the discernment of conditions (Ch. XIX); for in this interval the penetration of the specific characteristics of states predominates. The plane of full-understanding as investigation extends from comprehension by groups up to contemplation of rise and fall (XXI.3f.); for in this interval the penetration of the general characteristics predominates. The plane of full-understanding as abandoning extends from contemplation of dissolution onwards (XXI.10); for from there onwards the seven contemplations that effect the abandoning of the perception of permanence, etc., predominate thus:

- Contemplating [formations] as impermanent, a man abandons the perception of permanence.

- Contemplating [them] as painful, he abandons the perception of pleasure.

- Contemplating [them] as not-self, he abandons the perception of self.

- Becoming dispassionate, he abandons delighting.

- Causing fading away, he abandons greed.

- Causing cessation, he abandons originating.

- Relinquishing, he abandons grasping (Paṭis I 58).[2]

5. So, of these three kinds of full-understanding, only full-understanding as the known has been attained by this meditator as yet, which is because the delimitation of formations and the discernment of conditions have already been accomplished; the other two still remain to be attained. Hence it was said above: “Besides, knowledge of what is the path and what is not the path arises when full-understanding as investigation is occurring, and full-understanding as investigation comes next to full-understanding as the known. So this is also a reason why one who desires to accomplish this purification by knowledge and vision of what is the path and what is not the path should first of all apply himself to comprehension by groups” (§2).

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Tīraṇa could also be rendered by “judging.” On specific and general characteristics Vism-mhṭ says: “Hardness, touching, etc., as the respective characteristics of earth, contact, etc., which are observable at all three instants [of arising, presence and dissolution], are apprehended by their being established as the respective individual essences of definite materialness. But it is not so with the characteristics of impermanence, and so on. These are apprehended as though they were attributive material instances because they have to be apprehended under the respective headings of dissolution and rise and fall, of oppression, and of insusceptibility to the exercise of mastery” (Vism-mhṭ 779). See Ch. XXI, note 3.

The “planes” given here in §4 are not quite the same as described in XXII.107.

[2]:

“‘Contemplating as impermanent’ is contemplating, comprehending, formations in the aspect of impermanence. ‘The perception of permanence’ is the wrong perception that they are permanent, eternal; the kinds of consciousness associated with wrong view should be regarded as included under the heading of ‘perception.’ So too with what follows. ‘Becoming dispassionate’ is seeing formations with dispassion by means of the contemplation of dispassion induced by the contemplations of impermanence, and so on. ‘Delighting’ is craving accompanied by happiness. ‘Causing fading away’ is contemplating in such a way that greed (rāga) for formations does not arise owing to the causing of greed to fade (virajjana) by the contemplation of fading away (virāgānupassanā);for one who acts thus is said to abandon greed. ‘Causing cessation’ is contemplating in such a way that, by the contemplation of cessation, formations cease only, they do not arise in the future through a new becoming; since one who acts thus is said to abandon the arousing (originating) of formations because of producing the nature of non-arising. ‘Relinquishing’ is relinquishing in such a way that, by the contemplation of relinquishment, formations are not grasped anymore; hence he said, ‘He abandons grasping’;or the meaning is that he relinquishes apprehending [them] as permanent, and so on” (Vism-mhṭ 780).