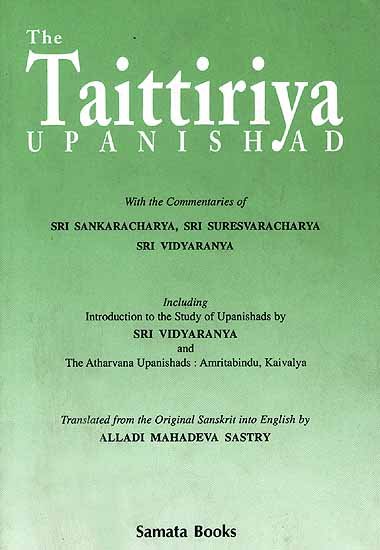

Taittiriya Upanishad

by A. Mahadeva Sastri | 1903 | 206,351 words | ISBN-10: 8185208115

The Taittiriya Upanishad is one of the older, "primary" Upanishads, part of the Yajur Veda. It says that the highest goal is to know the Brahman, for that is truth. It is divided into three sections, 1) the Siksha Valli, 2) the Brahmananda Valli and 3) the Bhrigu Valli. 1) The Siksha Valli deals with the discipline of Shiksha (which is ...

Chapter II - Brahman’s Existence as Creator

The purpose of the sequel.

In the sequel, the Upaniṣad proceeds to answer the foregoing questions.

And now, first of all, it proceeds to establish the very existence (of Brahman'.

As the two other questions presuppose the existence of Brahman, the śruti proceeds to establish, first of all, the existence of Brahman.—(S).

It has been said, “Real, Consciousness, Infinite is Brahman.” Now, as it is necessary to explain how Brahman is Real, the śruti proceeds with this, the present section. Brahman’s existence being once established, His reality is also established. It is, indeed, taught that “The Existent is the Real[1];” so that, existence being proved, reality also is proved.

(Question):—How do you know that the sequel is intended for this purpose (of proving the reality of Brahman by proving the existence of Brahman)?

(Answer):—By closely following the tenor of the texts. It is, indeed, this idea[2] (of existence) which runs through the succeeding passages such as the following:

“They declare That as Real.” “If this Ākāśa, (this) Bliss, existed not.”

As an answer to the disciple’s first question, i.e., the question concerning the existence of Brahman, the Guru proceeds to describe creation (sṛṣṭi) with a view to prove the existence of Brahman.

Brahman exists.

(Objection): —Now, it may be supposed that Brahman is altogether non-existent.—Why?—Because, that which exists, such as a pot, is perceived in actual experience; that which does not exist, such as the rabbit’s horn, is not perceived. Brahman, likewise, is not perceived; and so, not being perceived in actual experience, He does not exist.

(Answer): —Not so; for, Brahman is the Cause of ākāśa &c.

(To explain:—It cannot be that Brahman does not exist.—Why?—For, it is taught (in the śruti,[3] that ākāśa and all elseṛn the creation have been born of Brahman. It is a fact of common experience that that thing exists from which something else is born, as, for example, clay and the seed, which are the sources of a pot and a tree. So, being the cause of ākāśa &c., Brahman exists. Nothing that is born is ever found to have been born of non-existence. If the whole creation, comprising names and forms and so on, were born of non-existence, it would likewise be non-existent and could not therefore have been perceived (as existing). But it is perceived (as such). Therefore Brahman exists. If the creation were born of non-existence, it would, even when perceived, have been perceived only in association with non-existence (i.e., only as non-existent). And such is not the case. Therefore Brahman exists. Elsewhere in the words “How can existence be born of non-existence?”[4] the śruti has declared from the point of reason[5] the impossibility of the birth of existence from non-existence. It therefore stands to reason to say that Brahman is existent and existent only.

Moreover, the non-existent cannot be the Cause, because it has no existence. The Cause is that which exists before the effect. Non-existence (the void, śūnya) cannot therefore be a cause.

(Objection): —Brahman, too, cannot be the Cause, because He is immutable (kūṭastha).

(Answer):—Just as the magnet, while immutable in itself, can produce an effect, so also, Brahman may be the Cause. If the cause be a thing that is ever active, then, where is room for anything new? (To explain):—If it be held that the cause is a thing which is ever active, then, it is tantamount to saying that the cause is immutable, not undergoing change. If, on the contrary, again, it be held that the cause is a thing which is active only on a particular occasion, the cause must have been previously inactive, i.e., immutable.—(S & A).

Brahman’s Creative Will.

(Objection):—If Brahman be the cause like clay and the seed, then He would be insentient.

(Answer):—No; for, Brahman is one who has desires. Indeed, in our experience, there exists no insentient being having desires. And we have stated[6] that Brahman is Omniscient; and it is therefore but right to speak of Brahman as one who has desires.

Brahman is independent of desires.

(Objection): —Then, as one having desires, Brahman, like ourselves, has unattained objects of desire.[7]

(Answer):—No, because of His independence. Brahman’s desires do not rouse Him to action in the same way that impure desires influence others and guide their action.—How then (are they)?—They are true (satya) and wise (jñāna)[8] in themselves, one with Himself[9], and therefore pure. By them Brahman is not guided. It is, on the other hand, Brahman who guides them in accordance with the Karma of sentient beings. Brahman is thus independent as regards desires. Therefore, Brahman has no desires unattained.

And also because Brahman is independent of external factors. (That is to say), unlike the desires of other beings,—.(the desires) which lie beyond them[10], which are dependent on the operation of Dharma and other causes, and which stand (for their realisation) in need of additional aids such as the body (kārya, the effect, the physical body) and the sense-organs (karaṇa, the Liṅga-śarīra) distinct from the beings themselves,— Brahman’s desires are not dependent on external causes and the like. -What then?—They are one with Himself[11].

The Mīmāṃsā[12] answers the foregoing objection by comparing His desires to sportive acts and the respiratory process. He is also distinguished from jīvas by the fact that His desires are never frustrated. So says the śruti: “Of unfailing desires and of unfailing purposes He is.”[13]

It is this truth that the Upaniṣad teaches in the following words:

सोऽकामयत । बहु स्यां प्रजायेयेति ॥ ४ ॥

so'kāmayata | bahu syāṃ prajāyeyeti || 4 ||

4. He desired: many may I be, may I be born!

He, the Ātman, the Self,—from whom ākāśa was born,—desired, many may I be!

It is the Pratyagātman, associated with Āvidyā i. e., the Pratyagātman not fully realising Himself, and who was spoken of before as the source of ākāśa,—it is this Pratya-gātman that is here said to have desired; for, without avidyā, kāma (desire) cannot arise in any being whatever. —(S & A).

He: That Brahman who was spoken of as “the tail, the support” of tbe Anandamaya-kośa, and who was described as “the Self embodied’ of the five sheaths from the Annamaya to the Ānandamaya. He, this Ātman, who, prior to sṛṣṭi, was one alone without a second, desired, in virtue of association with His own potentiality (śakti). That is to say, the Māyā-śakti, that wonder-producing potentiality which is ever present in Ātman, modified itself into the form of desire. Certainly, without Māyā, there can arise no desire in the One Immutable Principle of Consciousness.

Duality is an illusion.

The śruti describes the form of His desire in the words “many may I be.”

(Question):—It may be asked, how can one thing become many, except by association with other things?

We see that the multiplicity of ākāśa arises from association with upādhis, with other things such as a pot. But, how can Brahman, who was without a second, become many?

(Answer):—The śruti answers in the words, “may I be born.”

That is to say, may I reproduce Myself increasingly, may I assume more forms than the one which has been hitherto in existence.

Brahman does not indeed multiply Himself by giving birth to things quite distinct, (as the father multiplies himself) by giving birth to a son.—How then?—It is by the manifestation of the name and form which have remained unmanifested in Himself.

The father who gives birth to a son remains a separate being. He himself is not born as the son. Similarly, in the present case, one may suppose that Brahman, the Creator of the universe, is not Himself born as the universe, and ask, how is it that the śruti represents Brahman as having desired to be so born? The answer is that name and form which come into being are not quite distinct from Brahman. Just as the waves manifesting themselves in the ocean are not quite distinct from the ocean, so also, name and form, which first reside unmanifested in Māyā, Brahman’s inherent potentiality (śakti), come into manifestation afterwards, and remaining one with Brahman in His essential nature as existence, become themselves manifested as existent. This very idea is expressed by the Vājasaneyins in the words “All this was then undeveloped. It became developed by name and form.”[14] Hence the propriety of the words “may I be born,” the Māyā of Brahman manifesting itself in the form of the universe.

When name and form which have remained unmanifested in the Ātman become differentiated in all their variety,[15] in no way abandoning their essential nature as Ātman[16], not existing in space and time apart from Brahman, then,by this differentiation of name and form, Brahman becomes manifold. In no other way can the partless Brahman become manifold, or become small. It is, for instance, through other things that ākāśa appears small or manifold. So it is through them[17] alone that Ātman becomes many. Indeed there exists nothing other than Ātman, no not-self—however subtle, removed and remote, whether of the past or the present or the future,—as distinguished from Brahman in space and time. Therefore name and form in all their variety have their being only in Brahman. Brahman’s being is not in them. They have no being when Brahman is ignored and are therefore said to have their being in Him. It is through these upādhis (of name and form) that Brahman is manifested to us as all categories of being,—as the knower, as the objects known, as knowledge, as words, as objects.

Just as a burning faggot, while remaining of one shape, puts on various shapes owing to some external causes,[18] so also the multiplicity of the Supreme Ātman is due to the illusion of names and forms. So, it is only by way of manifesting Himself in these illusory names and forms that the Lord must have desired to be born. These names and forms residing in the Ātman spring forth into manifestation in all variety from the Ātman, the Lord, in their due time and place, subject to the Karma of the (sentient beings in the) universe. It is this daily differentiation of names and forms from out of Viṣṇu which the śruti represents as Brahman becoming manifold, and which is like a juggler (māyin, magician) putting on manifold forms. Indeed, Brahman being without parts, it cannot be that He actually becomes manifold. Wherefore, it is only in a figurative sense that Brahman is spoken of as becoming manifold, in the same way that ākāśa becomes manifold through jars and other objects extending in space.—(S).

Brahman’s Creative Thought.

स तपोऽतप्यत ॥ ५ ॥

sa tapo'tapyata || 5 ||

5. He made tapas.

With this desire, He, the Ātman, made tapas. ‘Tapas’ here means ‘thought’, as śruti elsewhere says “whose tapas consists of thought itself[19] As he has attained all desires, the other kind of tapas[20] cannot be meant here.

The tapas (penance) of the common parlance, belonging as it does to the world of effects, cannot be meant here. The penance the śruti here speaks of is the īśvara’s thought concerning creation.— (S).

To the Supreme Lord (Parameśvara) the various forms of the penance of self-mortification can be of no avail.

Such tapas He made; that is to say, He thought about the design of the universe to be created.

स तपस्तप्त्वा । इदं सर्वमसृजत । यदिदं किञ्च ॥ ६ ॥

sa tapastaptvā | idaṃ sarvamasṛjata | yadidaṃ kiñca || 6 ||

6. Having made tapas, He sent forth all this, and what of this more.

Having thus thought, He emanated all this universe,— as the karma, or the past acts of sentient beings, and other operative circumstances determined,—in time and space, with names and forms as we experience them, as they are experienced by all sentient beings in all states of being. He emanated all this and whatever else is of the same nature.

The Īśvara, having pondered according to the śruti, emanated the universe, according to the desires and acts of the sentient beings to be born, in their proper forms and shapes.—(S).

A summary of the foregoing argument.

Here the existence of Paramātman is established on the following grounds:

- that He is the Being who willed.

- that Pie is the Being who thought.

- that He is the Being who created.

The Nihilist (asad-vādin) holds as follows: It may be inferred from experience that all that exists is composed of names and forms, as, for instance, ākāśa and other elements of matter, and the bodies composed of those elements of matter such as those of Devas and animals. But the Paramātman is distinct from name and form, as the śruti elsewhere says:

“He, who is called Akāśa, is the revealer of name and form. He, in whom these are, is Brahman.”[21]

As to the assertions such as “Paramātman is Brahman,” they cannot go to establish His existence,—inasmuch as they are mere fancies (vikalpas)—any more than the words “the rabbit’s horn” can establish the existence of the rabbit’s horn. Patañjali says:

“Fancy is a notion founded on a knowledge conveyed by words, but corresponding to which there is no object in reality.”[22]

So, Brahman, being devoid of name and form, is also devoid of existence which is always associated with a name and a form. This view is quite on all fours with the statements of the śruti such as the following:

“Non-existent, verily, this at first was.”[23]

“Whence words recede.”[24]

“Then follows the teaching ‘ not thus, not thus[25]

“Neither coarse nor fine, neither short nor long.”[26]

So, we conclude that Brahman does not exist.

As against the Nihilist who argues thus, the śruti establishes the existence of Brahman by an argument in the following form: The Paramātman, as the Being who desired, must be existent, just as a man who desires svarga and the like exists. He is also the Being who thought, and therefore, like other thinkers such as a king’s minister, He must be existent. He is also the creator, and therefore, like all other creators such as a potter who makes pots, He must be existent. The very existence you have asserted of names and forms is itself Brahman as we understand Him, the names and forms being mere illusions set up by Māyā in the substratum of Brahman who alone is existent. As to the texts of the śruti referred to as supporting the Nihilist’s position, their meaning will be explained in the sequel.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

i.e. existence and reality are synonymous.—(V).

[2]:

But not the idea of the wise or the unwise attaining or not attaining Brahman.—(V),

[3]:

In the words, “All this Ho created.

[4]:

Chhā. Up. 6-2-2.

[5]:

By adding the fact that non-existence does not run through the objects of experience.—(V.).

[6]:

While commenting on the passage Real, Consciousness, and Infinite is Brahman.”

[7]:

If Īśvara had desires caused by Māyā, then, like the jīva. He would not be ever-satisfied as He is said to be.

[8]:

Like Brahman.—(Y),

[9]:

Brahman as reflected in Māyā is the cause of the Universe. His desires are forms (pariṇāraas) of Māyā and are ensouled by Consciousness which is not overpowered by ignorance, avidyā, &c. They are therefore true and wise, like Brahman. As one with Brahman, as the upādhi of Brahman, they are unaffected by sin (adharma) and are therefore pure.—(A).

[10]:

Beyond the control of those beings.—(V).

[11]:

i. e., Their fulfilment is dependent on Himself alone,—(Y.)

[12]:

Vide Vedānta-Sūtras, II. i. 33.

[13]:

Chhā 8-1-5.

[14]:

Bṛ. Up. 1-4-7.

[15]:

As Tanmātras, as gross elements of matter, as the Mundane Egg, and as various forms of being within It.—(V).

[16]:

i.e., remaining all the while as one with the Self, their source,—not existing as distinct from the Self.

[17]:

Through name and form.

[18]:

When it is shaken or whirled round.

[19]:

Muṇḍ. Up. 1-1-9.

[20]:

Self-mortification through body and mind.

[21]:

Chhān. Up. 8-14-1.

[22]:

Yoga-sūtras 1-9.

[23]:

Tai. Up. 2-7-1.

[24]:

Ibid. 2-9-1.

[25]:

Bṛ. Up. 2-3-5.

[26]:

Bṛ. Up. 3-8-8.