Taittiriya Upanishad

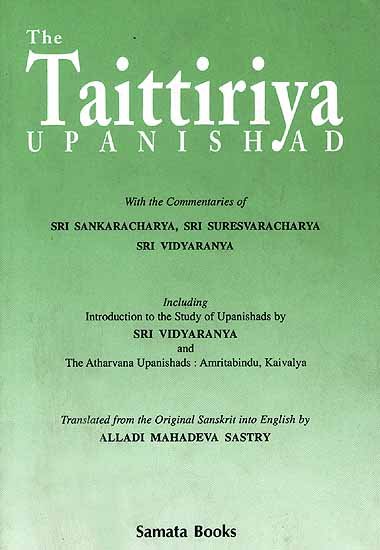

by A. Mahadeva Sastri | 1903 | 206,351 words | ISBN-10: 8185208115

The Taittiriya Upanishad is one of the older, "primary" Upanishads, part of the Yajur Veda. It says that the highest goal is to know the Brahman, for that is truth. It is divided into three sections, 1) the Siksha Valli, 2) the Brahmananda Valli and 3) the Bhrigu Valli. 1) The Siksha Valli deals with the discipline of Shiksha (which is ...

Chapter XI - Annamaya-kośa

Introduction.

In chapters VI to IX, it has been well established that the whole universe from ākāśa down to man has been evolved from Brahman endued with Māyā. This being established, it becomes quite evident that Brahman is infinite; for, as the effect has no existence apart from the cause, Brahman Himself is in the form of space, time and all things. Having thus established the infinitude of Brahman declared in the words “Real, Consciousness and Infinite is Brahman,” the śruti proceeds to establish the statement that He is ‘hid in the cave,’ by way of discriminating the real Brahman from the five kośas beginning with the Annamaya and ending with the Ānandamaya.

Composition of the Annamaya-kośa.

To treat first of the Annamaya-kośa:

स वा एष पुरुषोऽन्नरसमयः ॥ ४ ॥

sa vā eṣa puruṣo'nnarasamayaḥ || 4 ||

4. He, verily, is this man, formed of food-essence.

This human being whom we perceive is a vikāra or product of food-essence. It is, indeed, the semen,—the essence of all parts of the body, bearing the (generator’s) thought-impress of human form,—that here constitutes the seed; and he who is born from that seed (which bears the thought-impress of human form) must be likewise of human form; for, as a rule we find that all creatures that are born, of whatever class of beings, are of the same form as the parents.

(Question):—All creatures alike being formed of food-essence and descended from Brahman, why is man alone taken (for examination)?

(Answer):—Because of his importance.

(Question):—Wherein does his importance lie?

(Answer):—In so far as he is qualified for karma and jñāna, for acting and knowing aright. Man alone, indeed, is qualified for karma and jñāna, because he alone is competent to follow the teaching, and because he alone seeks the ends which they are intended to secure. Accordingly the śruti says elsewhere: “But in man the Self is more manifested” &c.[1] It is man whom the śruti seeks to unite to Brahman, the Innermost Being, through Vidyā or wisdom.

[2] With a view to transport man by the ship of Brahmavidya to the farthest shore of the great ocean of evil-producing kośas (sheaths), the śruti says “He, verily, is this man” etc. Here ‘He’ refers to the Ātman, the Self, the Primal Being; and ‘verily,’ shows that He is the Ātman taught in all Upaniṣads. In the words ‘this man’ the śruti teaches that the Ātman Himself has become the man of kośas by avidyā, by not knowing himself. Just as a rope becomes a serpent only by avidyā,—for, a rope can never actually become a serpent,—so, by avidyā Ātman becomes the man of five kośas and appears to suffer along with the kośas. ‘Annarasamaya’ means a thing formed of food-essence. Reason[3] as well as revelation[4] teach that the Supreme Self is not formed of any material, unlike a pot which is formed of clay. But we know that the body is made of food-essence. The śruti says that “He (the Self), verily, is this man formed of food,” simply because the physical body is an upādhi of the Self.—(S & A).

By “this man formed of food-essence” we should understand the piṇḍa or individual human organism only; but that organism is one with the Virāj, with the whole visible universe constituting the physical body of the Cosmic Soul. Elsewhere, in the words “The Self alone was all this in the beginning, in the form of man,”[5] the śruti teaches the unity of the body and the Virāj; and here, too, in the words “Those who contemplate upon Anna (food) as Brahman,” the śruti directs us to regard Brahman and Anna as one. When by upāsana the organism which is limited to the individual is unified with the Virāj or Cosmic Organism, Prāṇa (life) becomes also unified with Vāyu, the Hiraṇya-garbha; and then the Self in the upādhi of the Hiraṇya-garbha passes beyond the limits of individuality, in the same way that a lamp-light confined within a pot becomes diffused in space when the confining pot is broken to pieces—(S. & A.).

The human organism, composed of a head, hands, feet, etc., and which at the beginning of creation was evolved after the evolution of ākāśa and other things mentioned already,—that very human organism is the one which every man regards as ‘my body.’ Certainly, what a person now regards as his own body is not itself the one evolved at the beginning of creation; still, as both alike are formed of food-element evolved in the course of the evolution beginning with ākāśa, man’s body is of the same kind as the one evolved at the beginning of creation. Hence the words “He, verily, is this man.” The words “formed of food-essence (anna-rasa)” clearly point to this idea. There are six kinds of food-essence: sweet, acid, saline, bitter, acrid and astringent. The physical body is formed of these six essences of food. The essence of the food eaten by the parents is in due course converted into the seven principles of this body,—namely, skin, blood, flesh, fat, bone, marrow and semen; and on entering the womb it is again changed into a human body. The Garbha-upaniṣad says:

“The food-essence is of six kinds. From this essence blood is formed; from blood, flesh; from flesh, fat; from fat, bone; from bone, marrow; from marrow, semen. From a combination of semen and blood the fætus is formed.”

The gross physical body mentioned here as formed of food-essence includes also the subtle body lying within it, inasmuch as this latter body is formed of simple (a-pañchīkṛta, unquintupled, uncompounded) elements of matter (bhṇta) and is nourished and maintained by food, etc., eaten by man. That the subtle body is formed of elements of matter is declared by the Teacher in the following words:

“The five unquintupled primary elements of matter, and the senses which are evolved from them, constitute together the Liṅga-Śarīra composed of the seventeen constituents; the Liṅga-Śarīra thus being material.”[6]

That the subtle body is nourished and maintained by food, etc., is taught in the Chhāndogya:

“Formed of food, verily, is manas; formed of water is prāṇa; formed of fire is speech.”[7]

From our ordrinary experience it can be shewn that in the case of all beings, when manas is weakened by fasting, it is invigorated by breaking the fast. Similarly, we find in our experience that, when prāṇa or vitality is weakened by the fatigue of a journey, it is refreshed by drinking water. So also we see songsters purify their throats by drinking ghee, oil, and other tejasic (fiery) substances and thus improve their voice. The physical body which we perceive—formed of food, and associated with the Liṅga-deha (subtle body)which is composed of manas, prāṇa, speech, etc., and whose nature has just been described,—is the ādhyātmika, i.e., belongs to the individual soul. From this we may also understand the nature of the Ādhidaivika, the body of the Cosmic Soul, the Vairājic body called Brahmāṇḍa, the Mundane Egg.

The Vārtikakāra has described it as follows:

“Then came into being the Virāj, the manifested God, whose senses are Diś (space) and other (Devatās or Intelligences), who wears a body formed of the five gross elements of matter, and who glows with the consciousness ‘I am all’.”

The Annamaya-kośa has been described by the śruti only with a view to ultimately enable the disciple to understand the real nature of Brahman, just as the end of a tree’s branch is first shown with a view to point out the moon over against it.

Contemplation of the Annamaya-kośa.

The śruti now proceeds to represent for the purposes of contemplation the five parts of the Annamaya-kośa in the form of a bird as in the case of a sacrificial fire. The sacrificial fire arranged in the form of a hawk, a heron, or some other bird, has a head, two wings, a trunk and a tail. So also, here, every kośa is represented to be made up of five parts:

तस्येदमेव शिरः । अयं दक्षिणः पक्षः । अयमुत्तरः पक्षः । अयमात्मा । इदं पुच्छं प्रतिष्ठा ॥ ५ ॥

tasyedameva śiraḥ | ayaṃ dakṣiṇaḥ pakṣaḥ | ayamuttaraḥ pakṣaḥ | ayamātmā | idaṃ pucchaṃ pratiṣṭhā || 5 ||

5. This itself is his head; this is the right wing, this is the left wing, this is the self, this is the tail, the support.

The disciple’s mind having been accustomed to regard the non-self as the Self—to regard as the Self the several forms, bodies, or kośas which are external to the Self—it is impossible for it all at once to comprehend the Innermost Self without the support (of its former experience),[8] and to dwell in Him detached altogether from that support. Accordingly, the śruti tries to lead man within (to one self within another till the real Self is reached) by representing (the inner embodied selves, the Prāṇamaya and so on) after the fashion of the physical body, of that embodied self with which all are familiar,—i.e., by representing them as having a head, etc., like the Annamaya self,—in the same way that a man shows the moon shining over against a tree by first pointing to a branch of the tree.[9]

The Annamaya-kośa is here represented by the śruti as a bird, as having wings and a tail, in order that the Prāṇamaya and other kośas may also be represented in the form of a bird. The intellect will thereby be divested of its engrossment in external objects and can then be directed steadily to the self. No contemplation of a kośa is intended for the specific fruit spoken of here. The present section starts and concludes with a discussion of the unity of the Self and Brahman; therefore this unity must be the aim of its teaching. To suppose that the contemplation for a specific purpose is also intended here is to admit that the present section deals with two different topics, which is opposed to all principles of interpretation. As to the śruti speaking of the specific fruits, it should be construed into a mere praise of the intermediate steps in the process of Brahmavidyā, calculated to induce the student to push on the investigation with zest. By meditating upon the kośas one after another, the student realises their true nature. When the mind dwells steadily in one kośa and realises its true nature, it loses sight of all objects of its former regard; and when thus divested, gradually, of the idea of one kośa after another, the student’s mind is competent to dwell steadily in the Self.—(A).

Of the man formed of food-essence, what we call head is itself the head. In the case of the Prāṇamaya and the like, what is not actually the head is represented as the head; and to guard against the idea that the same may be the case here (i.e., with the Annamaya), the śruti emphasises, “this itself is the head”. The same is true with regard to wings, etc.—This, the right arm of the man facing the east, is the right wing; this, the left arm, is the left wing; this, the central part of the body, is the self, the trunk, as the śruti says, “The central one, verily, is the self of these limbs.” This, the part of the body below the navel,—the tail as it were, because, like the tail of a bull, it hangs down,—is the support, i.e., that by which man stands.

As to the Annamaya which is to be meditated upon, what we call head, the part of the body situated above the neck, is itself the head. There is no figure here. The two hands themselves we see are to be meditated upon as the two wings. The part of the body situated below the neck and above the navel is the self, the middle part of the body, the suitable abode of jīva.........It is plain that the part of

the human body below the navel is the support of the upper part. In the body of the bull and other animals, the tail forms a support in so far as it serves to drive away flies and musquitoes and the like. This idea of the tail being the support of the bodies is presented here for purposes of contemplation.[10]

As fashioned after the mould of the physical body, the Prāṇamaya and others to be mentioned below are also represented to be of the same form, having a head and so on; the molten mass of copper, for example, poured into the mould of an idol takes the form of that idol.

Though the Prāṇamaya and the other three kośas are not actually made up of,a head and so on, still, as the molten metal poured into a mould takes the form of that mould, so the Prāṇamaya and other kośas which lie within the Annamaya-kośa may be imagined to be moulded after the latter. Such a representation is only intended to facilitate the meditation and discrimination of the four kośas—(S&A)

A Mantra on the unity of the Virāj and the Annamaya.

Thus has been taught the form in which the Annamaya-kośa should be contemplated. Now, the śruti quotes a mantra with a view to confirm what has been taught in the Brāhmaṇa here regarding the kośa and its upāsana:

तदप्येष श्लोको भवति ॥ ६ ॥

[इति प्रथमोऽनुवाकः]tadapyeṣa śloko bhavati || 6 ||

[iti prathamo'nuvākaḥ]6. On that, too, there is this verse:[11]

अन्नाद्वै प्रजाः प्रजायन्ते । याः काश्च पृथिवीं श्रिताः । अथो अन्नेनैव जीवन्ति । अथैनदपि यन्त्यन्ततः । अन्नं हि भूतानां ज्येष्ठम् । तस्मात् सर्वौषधमुच्यते । सर्वं वै तेऽन्नमाप्नुवन्ति । येऽन्नं ब्रह्मोपासते । अन्नं हि भूतानां ज्येष्ठम् । तस्मात् सर्वौषधमुच्यते । अन्नाद् भूतानि जायन्ते । जातान्यन्नेन वर्धन्ते । अद्यतेऽत्ति च भूतानि । तस्मादन्नं तदुच्यत इति ॥ १ ॥

annādvai prajāḥ prajāyante | yāḥ kāśca pṛthivīṃ śritāḥ | atho annenaiva jīvanti | athainadapi yantyantataḥ | annaṃ hi bhūtānāṃ jyeṣṭham | tasmāt sarvauṣadhamucyate | sarvaṃ vai te'nnamāpnuvanti | ye'nnaṃ brahmopāsate | annaṃ hi bhūtānāṃ jyeṣṭham | tasmāt sarvauṣadhamucyate | annād bhūtāni jāyante | jātānyannena vardhante | adyate'tti ca bhūtāni | tasmādannaṃ taducyata iti || 1 ||

[Anuvaka II]

1 “From food indeed are (all) creatures born, whatever(creatures) dwell on earth; by food, again, surely they live; then again to the food they go at the end. Food, surely, is of beings the eldest; thence it is called the medicament of all. All food, verily, they obtain, who food as Brahman regard; for, food is the eldest of beings, and thence it is called the medicament of all. From food are beings born; when born, by food they grow. It is fed upon, and it feeds on beings; thence food it is called.”

Bearing on this teaching of the Brāhmaṇa, there is the following mantra which refers to the nature of the Annamaya-ātman, the self of the physical body.

The śloka is quoted here in corroboration of the teaching of the Brāhmaṇa, with the benevolent idea of impressing the truth the more firmly.—(S).

Just as a mantra was quoted before with reference to what was taught in the aphorism “the knower of Brahman reaches the Supreme,” so also a verse is quoted here in corroboration of what has been just taught. This verse consists of fourteen pādas or lines. Though no such metre is met with in ordinary language, this extraordinary metre must have been current in the Vedic literature.

The Virāj.

From food,[12] indeed, converted into rasa (chyle) and other forms, are born all creatures, moving and unmoving (sthāvara and jangama). Whatever creatures dwell on earth, all of them are born of food and food alone. After they are born, by food alone they live and grow. Then again, at the end when their growth, their life, has come to an end, to food they go; i.e., in food they are dissolved.—Why?—For, food is of all living beings the eldest, the first-born. Of the others,— of all creatures, of the Annamaya and other kośas,[13]— food is the source. All creatures are therefore born of food, live by food, and return into food at the end. Because such is the nature of food, it is therefore called the medicament of all living creatures, that which allays the scorching (hunger) in the body.

Food, the Virāj, was evolved before all creatures on earth, and is therefore the First-born. Hence the assertion of the Purāṇa “He verily was the first embodied one”. Those who know the real nature of food call it the medicament (auṣadha) of all, because it affords a drink that can assuage the fire of hunger which would otherwise have to feed upon the very dhātus or constituents of the body. This cow of food suckles her calf of the digestive fire in all beings, through the four udders of the four food-dishes.[14]—(S)

All creatures,—the womb-born, the egg-born, and so on,—all creatures that dwell on earth, are born of food (anna), as has been already shewn......The bodies of animals, etc., form the food of the tigers and the like; hence the assertion that they dissolve in food at the end. Because food is the source of the bodies of all living beings, it is the medicine of all, as removing the disease of hunger. By removing the disease of hunger, food forms the cause of a creature’s life, of its very existence.—The śruti speaks of food as the remover of hunger simply to shew that it is the cause of the existence of all creatures. The śruti has described the Annamaya-kośa at length by speaking of food as the cause of the birth, existence and dissolution of all living creatures.

Contemplation of the Virāj and its fruits.

The śruti then proceeds to declare the fruit that accrues to him who has realised the Food-Brahman, the unity of food and Brahman.—They who contemplate the Food-Brahman as directed above obtain all kinds of food. Because “I am born of food, I have my being in food, and I attain dissolution in food,” therefore, food is Brahman.[15] How, it may be asked, can the contemplation of the Self as food lead to the attainment of all food? The śruti answers: For, food is the eldest of all beings, because it was evolved before all creatures; and it is therefore said to be the medicine[16] of all. It therefore stands to reason that the worshipper of Ātman as food in the aggregate attains all food.

The śruti speaks of food as Brahman because food is the cause of the birth, existence, and destruction of the universe. He who contemplates this Brahman, the Virāj, fora long time with great reverence and uninterrupted devotion and contemplates the Virāj as one with the devotee himself,—he becomes one with the Virāj and attains all food that all individual creatures severally attain. That is to say, the devotee of the Virāj partakes of all food, like the Virāj Himself. In the words “This here is the Virāj” the Tāṇḍins declare that the Virāj is the eater of all food. How this is possible the śruti explains by declaring that the whole visible universe is pervaded by the Virāj as the eater thereof, as every effect must be pervaded by its cause.—(S)

Those men who contemplate Brahman in food, taking food as a symbol of Brahman,—i. e., those who elevate food in thought to the height of Brahman and contemplate it as having assumed the form of the physical body made up of a head, a tail and other members,—these devotees attain all food.—Or, the food which was at first evolved from Brahman through the evolution of ākāśa and so on is now manifested as the physical’ bodies of individual souls, such as human and other bodies, as also in the form of the Virāj, i.e., as the body of the Universal Soul. Those who contemplate Brahman as manifested in the upādhi of food thus transformed attain unity with the Universal Being, the Virāj, and partake of all kinds of food which all the different classes of living beings, from Brahman down to plants, severally attain, each class attaining the food appropriate to it.

Addressing at first the disciple who seeks to know the Truth, the śruti has declared “food, surely, is the eldest of beings,” etc., with a view to describe the nature of the Annamaya-kośa, the physical body, since knowledge of the body is a step on the path to knowledge of Brahman. And the śruti repeats the same statement again. with a view to extol the Being to be contemplated upon. The passage means: Because food (Anna) is the eldest-born, the cause of all living beings from man to the Virāj, therefore it is the medicament of all, as removing all diseases of saṃsāra. For, by practising contemplation on the line indicated above, one attains the Virāj, and in due course attains salvation as well.

“From food are beings born; when born, by food they grow.” This repetition of what has been already said is intended to mark the conclusion of the present subject.

The Virāj, here presented for contemplation, is a lofty Being, for the further reason that He is the cause of the origin and growth of the bodies of all living beings.

The Virāj as the nouṛṣer and the destroyer.

The etymology, too, of the word ‘anna’ points to the loftiness of Food as the cause of all bodies.

Now the śruti gives the etymology of the word ‘anna’. It is so called because it is eaten by all beings and is itself the eater of all beings. As eaten by all beings and as the eater of all beings, Food is called Anna.[17] The word “iti” (in the text) meaning ‘thus’ marks the close of the exposition of the first kośa.

‘Anna’ (Food) is so called because it is eaten by all beings for their living existence; or because it destroys all beings. It is a well-known fact that all bodies die of diseases generated by disorderly combinations of food-essences in them. Here, the śruti marks the close of the verse quoted, as well as the end of the exposition of the Annamaya-kośa.

Knowledge of the Annamaya-kośa is a stepping-stone to knowledge of Brahman.

To the man who seeks to know the nature of Brahman ‘hid in the cave’, the śruti has expounded the Annamaya-kośa as a step to the knowledge of Brahman. The exposition forms a step to the knowledge by way of removing all attachment to external objects—such as sons, friends, wife, home, land, property,—and confining the idea of self to one’s own body. Every living being naturally identifies himself with his sons, etc., as if they form his very self; and this fact is admitted by the śruti in the words “Thou art the very self, under the name ‘son’.”[18] In the Aitareyaka also it is said

“This self of his takes his place as to the good acts; while the other self, reaching the (old) age and having achieved all he had to do, departs.”[19] The meaning of the passage is this: A householder, gifted with a son, has two selves, one in the form of the son and the other in the form of the father. His self in the form of the son is installed in the house for the performance of the purificatory rites (puṇya-karma) enjoined in the śruti and the smṛti; whereas his self in the form of the father, having achieved all that he has had to do, dies, his life-period having been over. The Blessed Bhāṣyakāra (Śrī Śaṅkarāchārya) has also referred to this fact of experience in the following words: “when children, wife, etc., are defective or perfect, man thinks that he himself is defective or perfect, and thus ascribes to the Self the attributes of external things.” Since every man is aware that the son is distinct from himself, the notion that the son is himself is like the notion that “Devadatta is a lion.” Therefore the Annamaya-kośa has been expounded here with a view to shew this kind of its superiority as self,—i. e., with a view to confine the disciple’s idea of self within the limits of one’s own body by withdrawing the idea from the whole external world composed of sons, friends, etc. The śruti. will explain this clearly in the sequel, in the following words:

“He who thus knows, departing from this world, into this self formed of food doth pass.”[20]

There may be a person who, owing to the preponderance of the deeply ingrained seeds of attachment for external objects, does not, when once taught, take his stand in the Annamaya self. It is to enable such a man to do it that the contemplation of the Annamaya self has been taught. He who practises this contemplation, constantly fixing his thought on the Annamaya self, withdraws altogether from the external objects and takes his stand in the Annamaya self. If a devotee of this class be short-lived and die while still engaged in this contemplation without passing through the subsequent stages of investigating the real nature of the Prāṇamaya and other selves and thus perfecting the knowledge of the true nature of Brahman, then, he will attain all food as declared above.

It is this truth that the Lord has expressed in the following words

“Having attained to the worlds of the righteous and having dwelt there for eternal years, he who failed in yoga is reborn in a house of the pure and wealthy.”[21]

Thus with a view primarily to remove all attachment for external objects, the śruti has treated of the nature of the Annamaya-kośa, and has incidentally spoken of its upāsana and the fruit thereof.

![]()

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Aita. Āra. 2-3-2-5. The passage is quoted in full on page 311.

[2]:

Here the Vārtikakāra’s explanation differs from the Bhāṣyakāras,

[3]:

The reason is: that He has no parts, that He is unattached, and so on.

[4]:

“He is not born, He does not die,” etc. (Kaṭha-up. 2-18)

[5]:

Bṛ, Up. 1–4–1

[6]:

These seventeen constituents are: the five primary elements tīiefive jñāna-indriyas (senses of knowledge), the five karma-indriyas (senses of action), manas, and buddhi.

[7]:

Op. cit 6–5–4.

[8]:

i. e., independently of all reference to the kosas formerly regarded as selves.

[9]:

He who wants to show the moon to another first teaches that the end of the branch of the tree is the moon. When the eye has thus been directed towards the end of the branch, and has been withdrawn from all other directions, then the moon oyer against the end of the branch is shown.

[10]:

That is to say, the value of the idea consists in the fact that a contemplation thereof leads to a comprehension of the true nature of Brahman in man,—which is here the main subject of discourse. Brahman will be spoken of as the support of the Ānandamaya self.—(Tr.)

[11]:

According to the division current among the students of these days, the first anuvāka ends here. Some students give to these divisions the name ‘Khaṇḍas’ or sections. Sāyaṇa does not recognise this division and even condemns it as not founded on any logical division of subject-matter. He looks upon the whole Ānandavallī, beginning with “The knower of Brahman reaches the Supreme”, as the second anuvāka, the Peace-Chant being the first anuvāka. These two anuvākas with the Bhrigu-vallī, the third anuvāka,constitute what Sāyaṇa calls the Vāruṇī-Upaniṣad.

[12]:

i.e., from the Virāj.

[13]:

The Prāṇamaya and other kosas arc certainly not constituted of Anna, the physical food; but they attain growth by the food eaten by man.

[14]:

The four kinds of food are those which have to be eaten respectively by mastication, by sacking, by swallowing, and by licking.

[15]:

Food is Brahman, because it is the cause of tbe birth, existence, and dissolution of all Annamaya-kosas. Tbe disciple should contemplate on the idea “I am the Food-Brahman,” because it is not possible to attain all food without being embodied in tbe body of tbe Virāj, the Food-Brahman, and because the disciple cannot attain to that state without contemplating his unity with the Virāj.

[16]:

See the Vārtikakāra’s explanation on page 398.

[17]:

This etymology is intended to shew that the Prajāpati, who is manifested in the form of Food, exists in two forms, as both the eaten and the eater.

[18]:

The Taittirīya Ekāgnikāṇḍa. 2–11–33.

[19]:

Aita. Up, 4–4

[20]:

Tai. Up. 2–8.

[21]:

Bhag. Gītā. 6–41.