Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

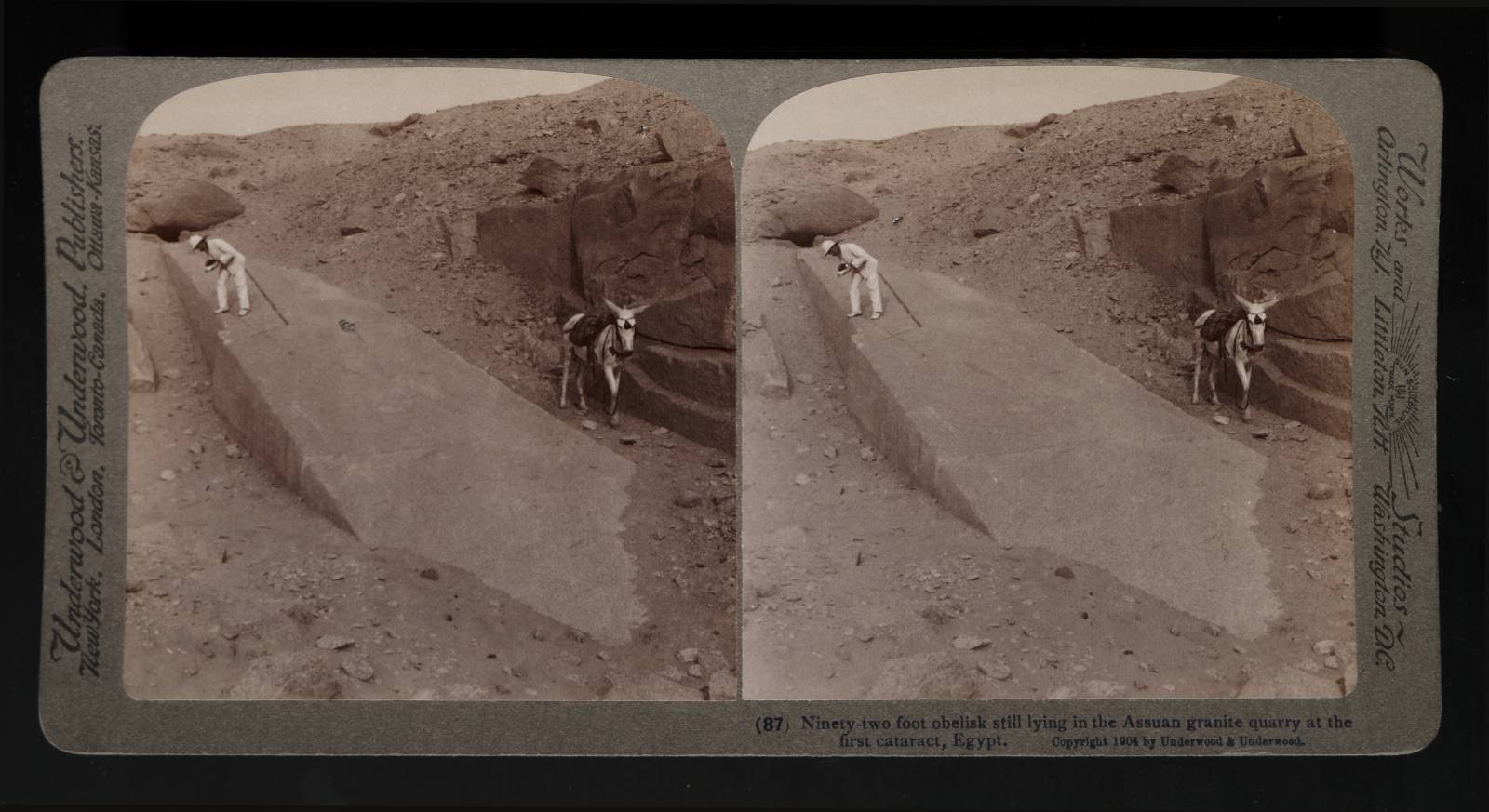

Position 87 - Ninety-two-foot Obelisk Still Lying In The Assuan Granite Quarry At The First Cataract

Recall the huge obelisks which we have seen at Heliopolis, Karnak and Luxor, for we are now in the quarry from which those vast monoliths came. This prostrate giant has never known what it is to stand, for he is still a part of Mother Earth, from which he has never been separated. If he could be placed erect, he would show a stature of 92 feet, which would place him among the tallest obelisks known. At the large end this shaft is 10½ feet thick. All the obelisks that we have seen once lay here as you see this one.

Recall the huge obelisks which we have seen at Heliopolis, Karnak and Luxor, for we are now in the quarry from which those vast monoliths came. This prostrate giant has never known what it is to stand, for he is still a part of Mother Earth, from which he has never been separated. If he could be placed erect, he would show a stature of 92 feet, which would place him among the tallest obelisks known. At the large end this shaft is 10½ feet thick. All the obelisks that we have seen once lay here as you see this one.

The method of separation from the rock of the quarry is interesting. A row of holes was drilled along the lower edge, where the obelisk joins the quarry rock; into these holes wooden wedges were firmly driven, and water was then poured into the wedges. The capillary attraction, or what is ordinarily called swelling of the wood, then gently but irresistibly forced off the obelisk and cracked it from the native rock beneath. It was then dragged upon a huge sledge to the neighboring river, and loaded upon a barge preparatory to floating it down the river. You remember that the barge of the architect Ineni for the 76-foot obelisk of Thutmosis I was 200 feet long and one-third as wide.

The reliefs of Queen Makere at Der el-Bahri show two of her obelisks being towed upon a huge barge, of which the dimensions are not given, but the galleys by which the barge is towed are 30 in number and have on the average 32 oarsmen in each, making some 960 oarsmen in all. As far back as the earliest dynasties or earlier, the Egyptians had learned the excellence of this Assuan granite, which fortunately for them crops out through the sandstone here at the first cataract; and (although at first under convoy of warships for protection against the hostile Nubians), they quarried it here at the dawn of history.

A nobleman of the 6th Dynasty boasts that he was able to quarry here with only one warship, as if such a thing had never been done before. We saw this granite in the monumental gate called the temple of the Sphinx, built in the Old Kingdom, and it was commonly employed for the finer and more important parts of the pyramids, like the chamber in the great pyramid where we saw the sarcophagus of Khufu.

The masses taken in one block from this quarry seem almost incredible in view of the limited knowledge of mechanics then possessed by the architects of the Pharaohs. Recall the colossus of Ramses II which we saw at the Ramesseum at Thebes, which was 57½ feet high and weighed 800 tons. That statue is of granite; it was quarried here and floated down the river in the same way. But when we recollect the 92-foot colossus of Tanis, which must have weighed some 900 tons, which was likewise taken out here, we shall realize what a place of mechanical miracles this quarry was.

For centuries it has been silent and deserted, or has served to satisfy the curiosity of visiting tourists, who, like this one here, with notebook in hand, have recorded the marvels left by the Pharaohs. North of us here, there is a colossus of Amenophis III lying on its back unfinished. The throne alone is over 12 feet high. A huge sarcophagus, also unfinished and evidently of Ptolemaic date is near by. The largest and heaviest of the surviving unfinished monuments in the quarry is the obelisk before us, for it must have weighed in the vicinity of 350 tons.

What would not the archaeologist give if he could see it rise from the rock to which it is bound, creep down to the river, float away on its long voyage, and struggle slowly upright before the pylons of some temple on the lower river! To watch the swarm of workmen from the Pharaoh's quarries accomplish a feat like that; to stand beside the vast monolith during every moment of its progress, notebook in hand—that would be a revelation which would immediately clear up many mysteries and save the archaeologists volumes of discussion.

Over on the island of Sehel there is an inscription of unusual interest which we must now see.