Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

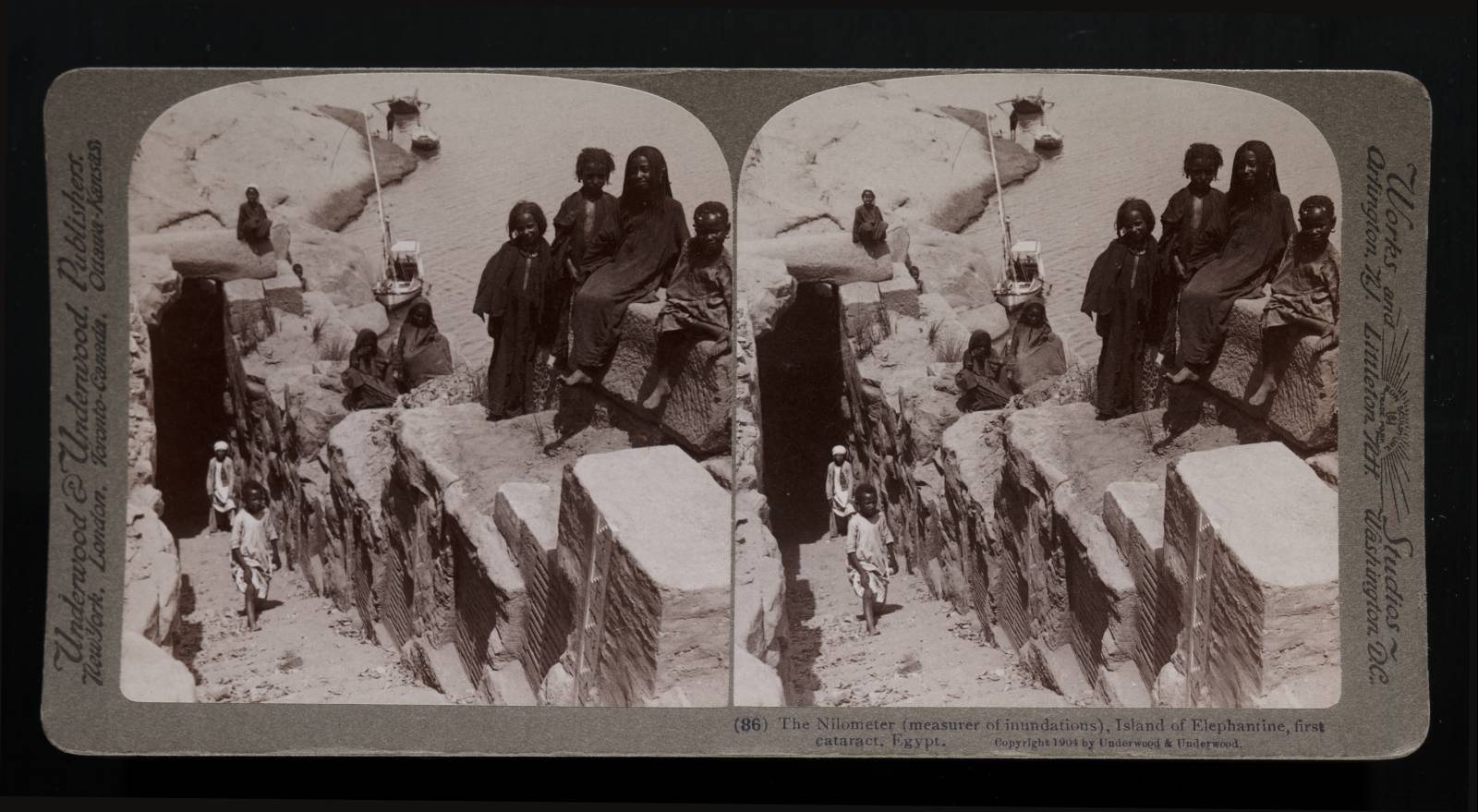

Position 86 - The Nilometer, The Measurer Of Inundations, Island Of Elephantine, First Cataract

After ages of use, this ancient instrument was cleaned out and restored to service by Ismail Pacha in 1870. It is very important at each stage of the inundation, to know whether the rise is equaling that of good years, or whether it is likely to fall short and cause famine and distress. As far back as the 19th century B. C. the kings of the Middle Kingdom recorded the height of the inundation year by year on the rocks above the second cataract, and those records are still there.

After ages of use, this ancient instrument was cleaned out and restored to service by Ismail Pacha in 1870. It is very important at each stage of the inundation, to know whether the rise is equaling that of good years, or whether it is likely to fall short and cause famine and distress. As far back as the 19th century B. C. the kings of the Middle Kingdom recorded the height of the inundation year by year on the rocks above the second cataract, and those records are still there.

It is difficult to determine how old this instrument on Elephantine is, but it is at least over 2,000 years, for Strabo, the great geographer of nearly 2,000 years ago, visited here and described it accurately, and his description, quoted in all the guide books, is still good. He says: “The Nilometer is well built of regular hewn stones, on the bank of the Nile, in which is recorded the rise of the stream, not only the maximum, but also the minimum and average rise, for the water in the well rises and falls with the stream.

On the side of the well are marks, measuring the height sufficient for the irrigation and the other water levels. These are observed and published for the general information. … This is of importance to the peasants, for the management of the water, the embankments, the canals, etc., and to the officials on account of the taxes. For the higher the rise of the water, the higher are the taxes.” Down at the bottom where the boy stands, the masonry is open to the river, so that, as Strabo says, the water in here rises with the rise of the stream.

You can see the graduated marks of which he speaks on the side wall, marking the depth at any given level of the surface. The one at the top, with oblique lines of white spots is modern Arabic, and the Arabic marks continue all the way down. This instrument is not arranged to measure the lowest levels of the river, which are of no practical importance, and thus as you will see by a glance at the water outside, it falls far below the lowest scale of this Nilometer. When it is at its lowest, the surface of the river outside is 49 feet below this highest mark here, which it reaches after it has risen and entered the Nilometer. This is nearly twice as much as the difference between highest and lowest level at Cairo.

We are here on the east side of the island, at its southern end, and you will find the Nilometer marked on the map (No. 17). We look northward, the island is on our left, and the channel which separates it from Assuan is on our right. Behind us is the cataract. You have already noticed these swarthy inhabitants of the island.

There are two villages of these people here, and you observe, especially in the face of the child on the extreme right, the African features and the darker hue of the skin. These are not Egyptians; we are here meeting our first Nubians, not speaking Arabic like the Egyptians, but the ancient tongue of Nubia, which they have spoken unbrokenly since the days when their forefathers made this frontier dangerous for the nobles and officials of the pyramid builders nearly 5,000 years ago.

Here, then, we make the transition from Egypt proper to the land of Nubia, and it is of importance to note, that whereas the Egyptian no longer speaks the language of those tombs which we have just visited, his former adversaries up to the very town which they once made precarious, still hold fast to the ancient tongue, which the Pharaoh's officers found here.

The granite quarries where the Egyptians found stone suitable for their buildings lie near us here on the east bank of the river. We shall go now a few miles south of Assuan, where we can see a great unfinished obelisk just as it was left by the early Egyptians.