Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

Position 23 - The Entrance To The Great Pyramid, The Sepulcher Of Khufu (in North Face), Seen From Below

Mounted upon the accumulated débris in the middle of the north face of the great pyramid, we are looking up at the opening. Is it possible, you are asking, that the Pharaohs thus advertised the entrances to their tombs and invited the tomb robber in this way to the place where he might gain access to the treasures of the interior? The recollection of the now vanished casing will immediately answer this question. What we see here is but the wreck of the ancient opening, which, piercing the casing just fifty-five feet and seven inches above the pavement, was so cunningly closed by a single flat slab of stone let into the surface, that it was invisible from below.

Mounted upon the accumulated débris in the middle of the north face of the great pyramid, we are looking up at the opening. Is it possible, you are asking, that the Pharaohs thus advertised the entrances to their tombs and invited the tomb robber in this way to the place where he might gain access to the treasures of the interior? The recollection of the now vanished casing will immediately answer this question. What we see here is but the wreck of the ancient opening, which, piercing the casing just fifty-five feet and seven inches above the pavement, was so cunningly closed by a single flat slab of stone let into the surface, that it was invisible from below.

Add to this the fact that it was not in the middle of this face of the pyramid, but twenty-four feet east of the middle, and we shall understand how baffling it must have been for the tomb robbers. Nevertheless, they somehow gained a knowledge of it, and the entrance was known in the time of Christ. In any case, Strabo speaks of a movable stone, which closed the entrance to the pyramid. This shows that it had already been robbed in antiquity, but it was later closed again and all knowledge of the entrance lost.

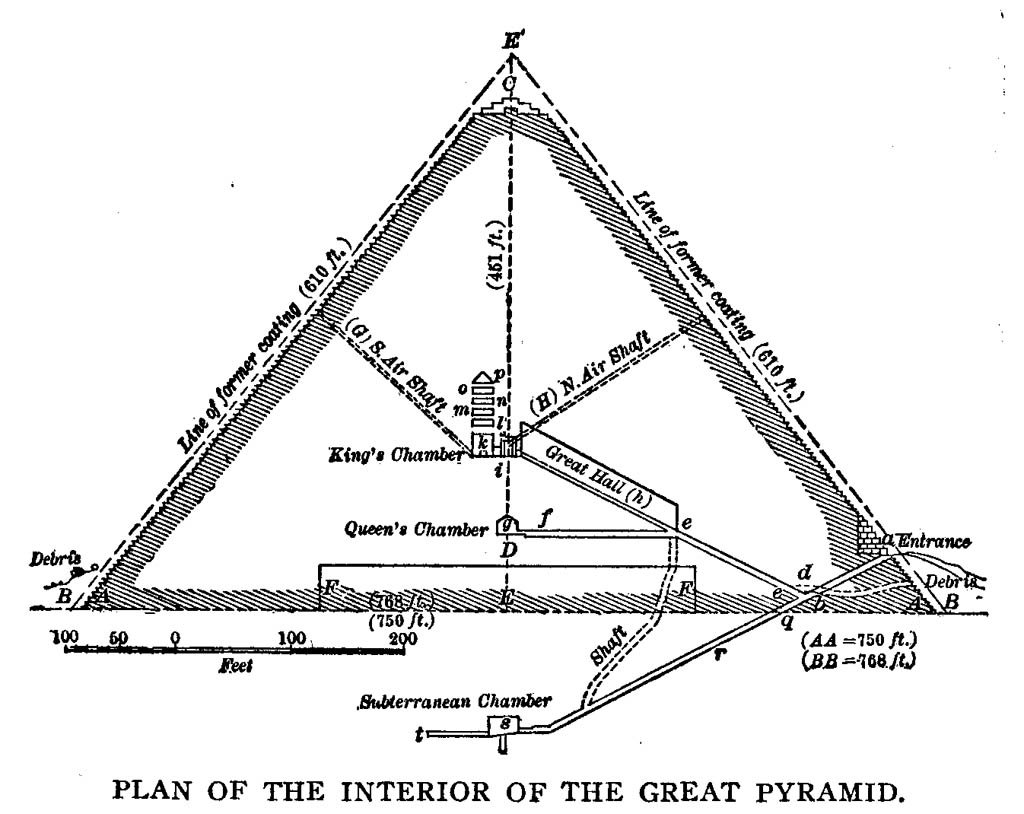

Image right: Plan Of The Interior Of The Great Pyramid.

That movable stone gave access to a descending passage only three and a half feet wide by four feet high, and protected from the enormous pressure from above by a superimposed peak of huge blocks of limestone, which you see in the rough opening above us. This passage points to the pole-star, and descending, rapidly passes out of the superstructure of masonry into the native rock beneath, upon which the pyramid rests, and after 345 feet terminates in a “subterranean chamber” hewn out of the rocks below the pyramid (see above Plan).

In the ceiling of this descending passage, ninety-two feet from the entrance, there begins an ascending passage, the lower end of which is cunningly closed by seventeen feet of plug blocks of granite. After 122 feet this ascending passage branches into two: one horizontal, leading to a chamber of limestone in the axis of the pyramid; the other still continuing to ascend, but expanding into a splendid hall, at the upper end of which, behind an ante-chamber, is the chamber in which the king was buried.

We shall presently stand at the upper end of this hall and look down, but before doing so, notice that dark hole in the masonry, partly stopped up with stones, on our extreme right. That hole is one of the best witnesses we possess to the skill with which the entrance here was closed, for the caliph el-Mamûn (813 to 833 A. D.), the son of the famous Harûn er-Rashid, whom we all know in the Arabian Nights, forced an entrance into the pyramid for the sake of the treasure, which it was supposed to contain; and this hole is his forced passage.

As might have been supposed, his workmen attacked the middle of this side, and they toiled for months, with the entrance passage just above their heads and a little to the east, till the sound of falling stones within the pyramid, led them toward the sound and they emerged upon the descending passage. But as the pyramid had been robbed they found nothing but the king's sarcophagus in the upper chamber, and to appease his disappointed followers the caliph was obliged to place some of his own treasure there, that they might find it and be satisfied.

We are now to take our position at the top of the “Great Hall” (see plan), and look down its entire length.