Egypt Through The Stereoscope

A Journey Through The Land Of The Pharaohs

by James Henry Breasted | 1908 | 103,705 words

Examines how stereographs were used as a means of virtual travel. Focuses on James Henry Breasted's "Egypt through the Stereoscope" (1905, 1908). Provides context for resources in the Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Part 3 of a 4 part course called "History through the Stereoscope."...

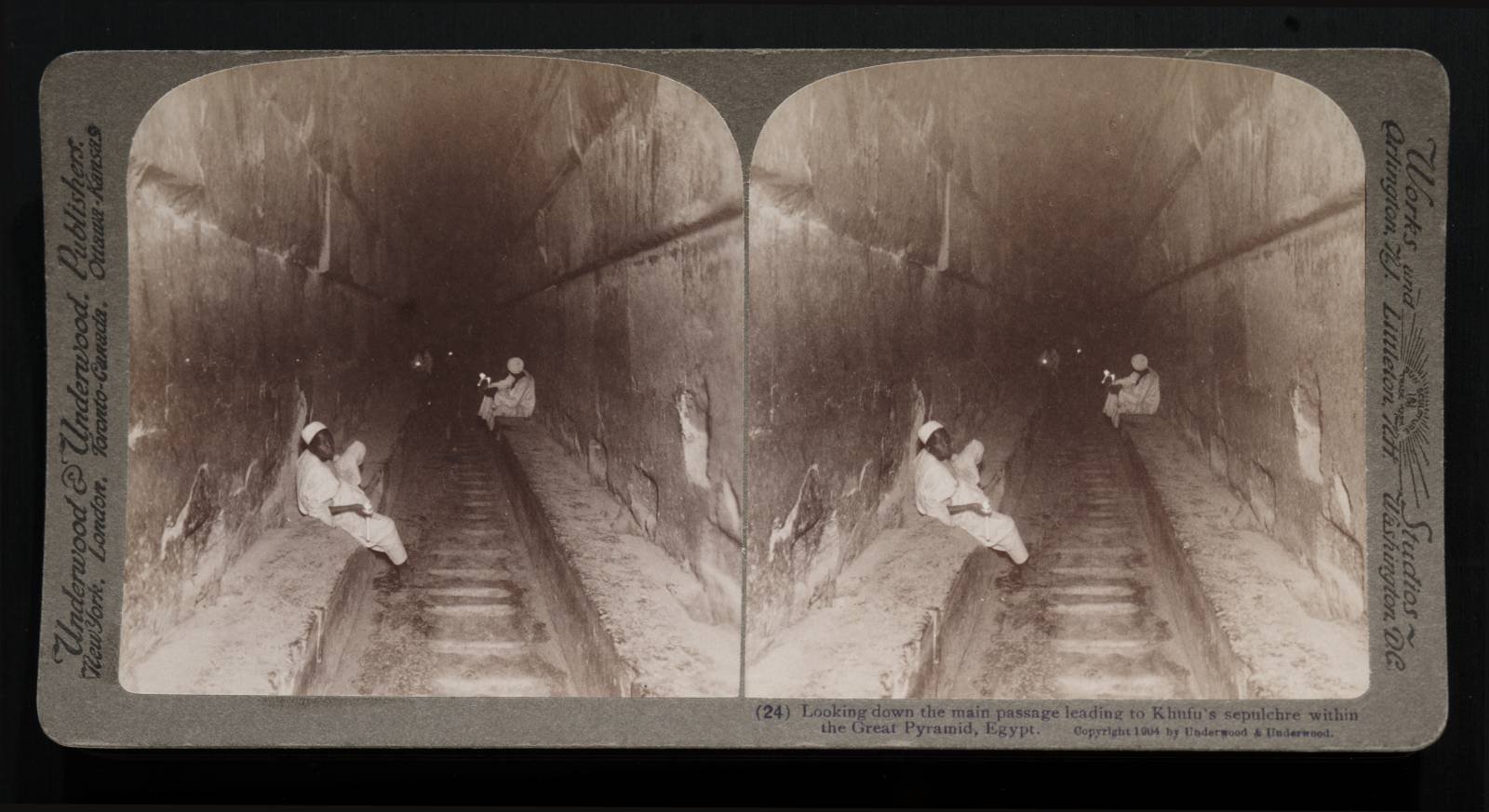

Position 24 - Looking Down The Main Passage Leading To Khufu's Sepulcher Within The Great Pyramid

What a gloomy, forbidding place! The bats flitting silently hither and thither whisk into our faces draughts of the stifling air, superheated by the suns of five thousand years, which have shone upon the pyramid until it glows like a furnace. It is intolerable, and the perspiration pours down our faces as we rest after the ascent. We are at the top of the grand hall and are looking down its slippery slope, congratulating ourselves that we have reached the level at the top; for without the ready assistance of the Arabs, the ascent of the hall is none too easy, and the cumulative velocity of a slide down that long, steep floor is no light matter when one reaches the bottom.

What a gloomy, forbidding place! The bats flitting silently hither and thither whisk into our faces draughts of the stifling air, superheated by the suns of five thousand years, which have shone upon the pyramid until it glows like a furnace. It is intolerable, and the perspiration pours down our faces as we rest after the ascent. We are at the top of the grand hall and are looking down its slippery slope, congratulating ourselves that we have reached the level at the top; for without the ready assistance of the Arabs, the ascent of the hall is none too easy, and the cumulative velocity of a slide down that long, steep floor is no light matter when one reaches the bottom.

One hundred and fifty-seven feet long and twenty-eight feet high is this wonderful hall, and the four natives with candles stationed along the descent may indicate its vast extent, as the last candle at the lower end glimmers in the distance. But it is very narrow in proportion to its length, for the side walls are only four cubits apart, that is, less than seven feet. The ramps on either side, upon which our natives are sitting, are each a cubit thick, leaving the width of the floor only two cubits, less than three and a half feet.

Overhead, beginning with the third course above the ramps, the courses project, each beyond the next lower one, for seven courses to the roof, lost in the gloom above. The projection of each of the seven courses is just a palm, so that the total projection of seven palms is exactly a cubit from either side. This makes the distance between the side walls at the roof two cubits; that is, the roof, like the floor between the ramps, is just two cubits wide, a little over forty-one inches.

This gradual narrowing toward the roof is, of course, for safety, as the roof must support the enormous weight of the masonry above. Some of the blocks of the side walls are not accurately dressed on the exposed surface, but if you will closely examine the joints between the first and second courses above the ramps, you will see that the surfaces now in contact are set together so skilfully that the seam can only with difficulty be discovered.

Indeed there are twenty ton blocks in this pyramid which are set together with a contact of one five-hundredth of an inch, an accuracy which not only surpasses the modern mason's straight edge, says Petrie, but quite equals that of the modern manufacturing optician. How many centuries of development must have been required to attain the skill to do work on such a grand scale, and at the same time with such exquisite nicety!

Up this superb hall the body of the king was borne on the day of burial, and those cuttings in the side walls just above the ramps, were probably for the reception of the timbers intended to facilitate the ascent. The chamber behind us in which the body was to rest is not less remarkable than the grand hall down which we look, and there we are now permitted to take up our station. See the “King's Chamber” in the plan on page 129.