The civilization of Babylonia and Assyria

Its remains, language, history, religion, commerce, law, art, and literature

by Morris Jastrow | 1915 | 168,585 words

This work attempts to present a study of the unprecedented civilizations that flourished in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley many thousands of years ago. Spreading northward into present-day Turkey and Iran, the land known by the Greeks as Mesopotamia flourished until just before the Christian era....

Part I

AT the outset of a discussion of the art of Babylonia and Assyria, it is natural to institute a comparison with that of the other great civilization of high antiquity Egypt. Leaving aside the question not yet ripe for solution, whether the culture of the Nile is earlier than that of the Euphrates Valley or vice versa, though the indications at present are in favor of the former alternative, there are certain physical features which the two countries have in common, which help to explain the rise of a high order of culture in both.

The warm climate during the greater portion of the year, suitable for a population as yet unable to protect itself against a more rigorous one, is divided in both the Euphrates Valley and in Upper Egypt into two seasons a dry season beginning in the spring and extending till the late fall, followed by several months of rain and storms during which the Nile in Egypt, and the Euphrates and Tigris in Babylonia overstep their bounds and flood large areas.

While this occurrence often brought about devastation prior to the construction of protective irrigation canals, through the perfection of a system to direct the overflow into the fields, it resulted in a fertility which rendered agriculture carried on with primitive methods, a comparatively easy task that was rewarded by rich returns.

The contrast between the two civilizations, on the other hand, which is particularly noticeable in the art, is due to the abundant presence of stone and wood in the one country, and the almost 'total absence of stone in the other. In place, therefore, of the massive stone structures of Egypt temples with large stone columns, elaborate rock tombs, mastabas and huge pyramids we have in the Euphrates Valley constructions limited by the use of the clay of the native soil, which forms the natural and practically exclusive building material.

Stones of various kinds from the hard diorite and basalt to several varieties of limestone and alabaster were, to be sure, imported at an early period from the mountainous district to the east and northeast as well as from northern Arabia and probably also from Egypt and Nubia, while wood was brought from the forests of Lebanon and other districts ; but the difficulties involved in procuring such material had as a natural result its rather limited use in architecture and proved a check to the artistic instinct in the development of stone sculpture. T

he hindrance was less felt in the case of moulding and designing in copper and iron and in the artistic employment of silver, gold and bronze and in carvings on bone and shell in which a high degree of skill was achieved at an early period. (See PI. 74.)

The dependence of architecture upon the material accessible for building purposes brings about a further differentiation between Babylonian and Assyrian constructions, and this despite the fact that the art, as the entire civilization of Assyria, is merely a northward extension of the Euphratean culture. Limestone and alabaster were abundant in Assyria, and the proximity to the mountains made it possible to obtain harder stones with comparatively little difficulty.

The larger employment of stone in the Assyrian temples and palaces thus became a characteristic feature, whereas the use of such material at all times remained exceptional in the large structures in the south.

Taking up first the older constructions in the south, it is interesting to note at the outset the shape of the bricks which during the period when the Sumerians were in control were plano-convex and oblong, while as we approach the time when the Semites assume the supremacy, the older form yields to square bricks that were also large and flat. [1] In time, a preference arose for a smaller brick about twelve inches square, and this remained in use with some variations. For the important parts of the building, including the outer layers, kiln-burnt bricks were used, but for the great brick masses sun-dried bricks of crude variety appeared to suffice.

At what time it became customary to paint colored designs on the bricks we are unable to say, but from the circumstance that painted pottery and vases of various designs were found in the lower layers at Telloh and Nippur, it is a fair inference that the art reverts to a very early period. At all events, we find it largely employed in the bricks of Assyrian palaces of the ninth, eighth and seventh centuries B.C., the colors either being simply placed on a coating of plaster over the bricks, or the designs were drawn on the bricks, placed together and covered with a colored glaze or varnish, which upon being burnt accentuated the brilliancy of the hues.

The chief colors employed were yellow, blue, red and white. [2] It is in the constructions of the days of Nebuchadnezzar II. that this art of glazed tiles reaches its highest form of perfection. The procession street leading to the temple of Marduk along which on festive occasions the statues of the gods were carried in solemn procession was lined with magnificently glazed tiles, representing figures of lions marching along in majestic dignity.

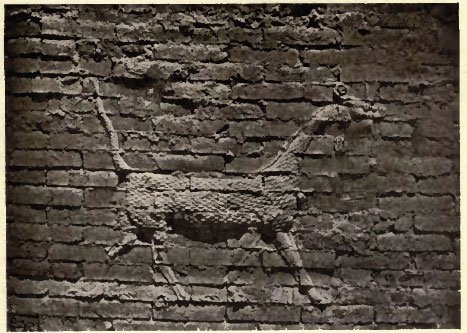

The background is dark blue, the lion itself is yellow, while running along the upper and lower edges are small white rosettes with a touch of yellow in the centre. Similarly, running along and around the outer and inner walls of the great Ishtar gate, excavated by the German expedition in Babylon and which formed the approach to the temple of Marduk, there were alternating rows of unicorns and dragons made in the same manner as the lions, and showing the same traces of the original, brilliant coloring.

It is estimated that there were at least fifteen rows of such glazed designs rising to a height of about forty feet. From the Babylonians this elaborate and effective method of decorating exterior and interior walls passed to the Persians, who carried it to an even greater degree of perfection. [3]

Large numbers of painted and enamelled bricks were found at Khorsabad and Nimrud by Botta and Layard respectively, which exhibited the remains of continuous patterns and of more or less elaborate designs, serving as decorations of the walls and arched gateways of the royal palaces. One of these decorated arches restored from numerous fragments portrays in conventionalized form the familiar winged creatures a lower order of deities standing before a large palmette which has become one of the conventionalized substitutes of the sacred tree. [4]

Another elaborate design in one of the palaces of Nimrud, repeated like a modern wall paper pattern, showed a crouching bull with decorative borders above and below. This style of decoration was extended to the gates and to the doorways leading from one division of the palace to the other as well as to floors which were similarly often found covered with elaborate geometrical and flowered designs that bore traces of coloring. [5]

PLATE XXXVII

Fig. 1, Dragon on colored, glazed tiles (Babylon)

Fig. 2, Bull on colored, glazed tiles (Babylon)

We are therefore justified in concluding that it was customary in both Babylonia and Assyria to cover the exteriors of temples and gateways as well as of palaces with decorative designs, flowers, geometrical patterns and pictorial representations on glazed bricks and that this method of decoration was extended to the interior halls and the gates or doors, leading from one section of a temple or palace to the other, and even to the exterior of the staged towers, though the extent to which this was carried in the case of these towers is still in doubt. In the case of interior decoration, less exposed to atmospheric influences, direct painting on the stucco with which the brick walls were covered frequently took the place of glazed bricks. The effect of this manner of decoration and particularly of the colored glazed tiles must have been striking in the extreme.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

At Nippur, e.g., the bricks of the Sargon period were found to measure twenty inches square, but were only 3J4 inches thick.

[2]:

An analysis of the colors showed that the yellow was anti- moniate of lead, the blue glaze is copper with some lead to facilitate the fusion of the lead, the white is oxide of tin, and the red a sub- oxide of copper. Cf. Layard, Discoveries vn the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon (New York ed. 1863), p. 166. 24

[3]:

See the illustration in Perrot and Chipiez, History of Art in Persia (London, 1892), facing p. 420.

[4]:

See Plate XVIII, Pig. 2 and Place, Ninive et I'Assyrie (Paris, 1867), PI. 14-17.

[5]:

Traces of colored tiles red, black and white were found in the case of the stage-tower at Khorsabad (see Botta et Flandin Monument de Ninive, PI. 155-156), but the conclusions drawn there- from that each of the seven stages bore a different color and that these colors stood in some relationship to the planets is not justified.