Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria

by Morris Jastrow | 1911 | 121,372 words

More than ten years after publishing his book on Babylonian and Assyrian religion, Morris Jastrow was invited to give a series of lectures. These lectures on the religious beliefs and practices in Babylonia and Assyria included: - Culture and Religion - The Pantheon - Divination - Astrology - The Temples and the Cults - Ethics and Life After Death...

Lecture III - Divination

THE longing to penetrate the future is one of the active, impelling motives in all religions, ancient and modern. The hourly needs of daily life, combined with an instinctive dread of the unknown, lead man to turn to the Powers, on which he knows himself dependent, for some signs which may indicate what these Powers have in mind to do. Divination at one end of the chain, and uplifting invocation at the other, are prompted by the longing to break the fetters, and tear the veil from the mysterious future. The chief function of the priest is to act as mediator or interpreter between the deity and the worshippers in order that the latter may obtain guidance in the affairs of daily life. Success in any undertaking being dependent upon the co-operation of the gods, it was all important to ascertain whether or not that co-operation be forthcoming. The constant, unforeseen changes in nature, in the varying appearance of the heavens, in the unstable phenomena on earth, thus found expression in man’s associating caprice and changeability with the arbiters of human destinies. One could never be sure of the mood of the higher Powers. They smiled one day only to frown the next. It: was, therefore, a matter of incalculable practical importance to learn if possible their disposition at any given' fnoment. The cult of Babylonia and Assyria, accordingly, revolves to a large extent around methods for divining the future, and we now proceed to inquire, what these methods were.

In any general survey of the vast,.almost boundless, field of divination, we may distinguish'two’divisions; one we may somewhat vaguely designate as voluntary divination, the other aś involuntary divination. By voluntary divination is meant an act of deliberately seeking out some.object through which it is hoped to secure a sign indicative of future events. So, e.g., the common practice among ancient Arabs of marking arrows, and then throwing them before an image or symbol of some deity, and according to where they lodged or the side on which they fell, to draw a conclusion as to what the deity had in mind to do or what he desired of his worshippers; this would fall within the category of voluntary divination. All methods of deciding upon any course of action by lot belong to the same class, since the decision deliberately sought would be supposed to be an indication of the divine will. Sending forth birds and observing their flight, as the Etruscans were accustomed to do, would represent another means of voluntary divination, the conclusions drawn from the direction and character of the flight being based upon a system more or less artifically devised. When the ancient Hebrews consulted the Teraphim, which were probably images or symbols of Jahweh (or some other god), they were engaged in an act of voluntary divination, though the details of its method have escaped us. Similarly, the incident related in the Book of Samuel, (I., chap. xx.,) where Jonathan is portrayed as shooting arrows and announcing the result to his companion David, was in reality a species of voluntary divination, though no longer so interpreted by the later compilers.

The field of involuntary divination, wherein signs indicating the purpose of the gods are not sought but forced upon our notice in spite of ourselves, is still larger. The phenomena in the heavens constitute the most conspicuous example of involuntary divination. The changes in the skies from night to night were supposed to correspond to variations in the dispositions of the gods, who were identified or associated with the planets and constellations. The signs were there and cried out, as it were, for an interpretation. All unusual incidents, whether in nature, such as sudden, unexpected storms, thunder out of a cloudless sky, cloud-bursts, unusually severe inundations, destructive tornadoes, swarms of locusts; or incidents in life that for one reason or another rivetted attention, such as dreams, snakes in the path, strange dogs of various colours, deformities or monstrosities in the young of animals, malformations of human offspring, the birth of twins and triplets, or a litter of pigs unusually large or unusually small—in short, anything which, whether really unusual or not, had any feature which gave it prominence, might be a sign sent by some god, and in any event demanded an interpretation by those who were supposed to possess the capacity to read in these signs the will and intention of the higher Powers.

Both voluntary and involuntary divination have a large share in the practical religion of Babylonia and Assyria. As examples of the former class we find the pouring of drops of oil in a bowl or goblet of water, and according to the number of bubbles, the side on which the bubbles were formed, the behaviour of the bubbles, as they first sank and then rose to the surface, and their line of formation, etc.,—from all these, conclusions were drawn as to their portents. In involuntary divination we find dreams, behaviour of animals, peculiar signs in or on new-born infants, or on the young of animals, strange phenomena in daily life, all carefully noted by the priests. These were interpreted according to a system, based in part upon observation of what in the past had actually followed any striking occurrence, with the assumption, resting on the illogical principle of post hoc , propter hoc, that the same circumstances would bring about a like result.

There are, however, two methods of divination among the Babylonians and Assyrians which take so prominent a part in their religion and enter so closely into it, as to overshadow all others. One of these methods, involving the inspection of the liver of the sacrificial animal, falls within the category of voluntary divination, the other, based on the observation and study of the phenomena of the heavens,—including clouds and storms as well as the stars,— belongs to the category of involuntary divination. Of the two, the former is a direct outcome of popular beliefs, while the latter is the result of speculation in the temple schools. The two methods therefore illustrate the two phases to be noted in the religion, the beliefs and practice evolved among the people, though under the guidance of the priests as the mediators between the gods and their worshippers, and the more or less theoretical amplifications of these beliefs along lines of thought that represent early attempts at systems of theology.

II

So deeply rooted is the belief that through a sacrificial animal a sign indicative of the divine purpose can be obtained, that the idea of tribute involved in offering an animal appears, so far as the Babylonian religion is concerned, to have been of a secondary character, if not indeed a later addition to the divina-tory aim. The theory upon which divination by the means of the liver rested is both curious and interesting. It was believed that the god to whom an animal was offered identified himself for the nonce with the proffered gift. The god in accepting the animal became, as it were, united to it, in much the same way as those who actually eat it. It lies beyond our scope to explain the origin of animal sacrifice, but in ancient religions the frequent association and identification of gods with animals suggest that the animal is sanctified by the sacrifice, acquiring the very attributes which were associated with the god to whom it is offered. Be this, however, as it may, it seems certain that in animal sacrifice an essential feature is the belief that the soul or spirit of the god becomes identical with the soul of the sacrificial animal. The two souls become attuned to one another, like two watches regulated to keep the same time. Through the soul of the animal, therefore, a visible means was obtained for studying the soul of the god, thus enabling mortals to peer, as it were, into the mental workshop of the gods and to surprise them at work, planning future events on earth—which were due, according to the current belief, to their direct initiative.

But where was the soul of the god? Using the term soul in the popularly accepted sense, it is not surprising to find mankind, while in a state of primitive culture, making the attempt to localise what it conceived to be the soul or vital essence of an animate being. Nations, even in an advanced state of culture, speak in figurative language of the heart or brain as comprising the essence or soul of being; and even after that stage of mental development is passed, where the soul is sought for in any specific human organ, human speech still retains traces of the material views once commonly associated with the soul. A goodly part of mankind’s mental and physical efforts may be said to be engrossed with this search for the human soul.[1]

In most of the Aryan and Semitic languages, the word for soul means “breath,” and rests upon the notion that the actual breath, emitted through the mouth, represents the real soul. This is still a widespread popular belief. Antecedent to this stage we find three organs of the human body—liver, heart, and brain—receiving in turn the honour of being the seat of the soul. This order of enumeration represents the successive stages in these simple-minded endeavours. Among people of to-day still living in a state of primitive culture, we find traces of the belief which places the soul in the liver. The natives of Borneo before entering on a war are still in the habit of killing a pig, and of inspecting the liver as a means of ascertaining whether or not the moment chosen for the attack is propitious; and, similarly, when a chieftain is taken ill, it is believed that, through the liver of a pig offered to a deity, the intention of the god, as to whether the victim of the disease shall recover or succumb, will be revealed.[2]

The reason why the liver should have been selected as the seat of life is not hard to discover. Blood was, naturally, and indeed by all peoples, identified with life; and the liver, being a noticeably bloody organ, containing about one sixth of the blood in the human body, and in the case of some animals even more than one sixth, was not unnaturally regarded as the source of the blood whence it was distributed throughout the body. The transfer of the locality of the soul from the liver to the heart, and later to the brain, follows, in fact, the course of progress in anatomical knowledge.[3] In the history of medicine among the ancients we find the functions of the liver recognised earlier than those of the heart. When it is borne in mind that only a few centuries have passed since Harvey definitely established the circulation of the blood, it will not be surprising that for a long time the liver was held to be the seat of the blood and, therefore, of life. The Babylonians of a later period seem to have attained to a knowledge of the important part exerted by the heart in the human organism, as did also the Hebrews, who advanced to the stage of regarding the heart as the seat of the intellect. The Babylonian language retains traces, however, of the earlier view. We find the word “liver” used in hymns and other compositions, precisely as we use the word “heart,” though when both terms are employed, the heart generally precedes the liver.

There are traces of this usage in Hebrew poetry, e.g., in the Book of Lamentations (ii., n), where, to express the grief of Jerusalem, personified as a mother robbed of her children, the poet makes her exclaim, “My liver is poured out on the ground,” to convey the view that her very life is crushed. In Proverbs vii., 23, the foolish, young man is described as caught in the net, spread by the worthless woman, “like a bird in trap,” and when he is struck by her arrows does not know that it is “his liver” which is in the hazard. In order to explain the meaning, the text adds as a synonym to “liver” the word “soul”—a further illustration of the synonymity of the two terms.

The Arabic language also furnishes traces of this early conception of the liver as comprising the entire range of soul-life—the emotions and the intellectual functions.

A tradition, recording Mohammed’s grief on hearing of the suspicion against the fidelity of his favourite wife, makes the prophet exclaim,

“I cried for two days and one night until I thought that my liver would crack”[4]

—precisely as we should say, “I thought my heart would break.” Similarly, in Greek poetry (which reveals archaic usage as does poetry everywhere,) the word “liver” is employed where prose would use “heart,” when indicating the essence of life. Theocritus, in describing the lover fatally wounded by the arrows of love, speaks of his being “hit in the liver,” where we should say that he was “struck to the heart”; and if, in the myth of Prometheus, the benefactor of mankind is punished by having his liver perpetually renewed and eaten by a vulture, it shows that the myth originated in the early period when the liver was still commonly regarded as the seat of life. The renewal of the liver is the renewal of life, and the tragic character of the punishment consists in enduring the tortures of death continually, and yet being condemned to live for ever. All this points unmistakably to the once generally prevailing view which assigned to the liver the preeminent place among the organs as the seat of the intellect , of all the emotions—both the higher and the lower,—and of the other qualities which we commonly associate with the soul.

There is no indication that the Babylonians, or for that matter any branch of the ancient Semites, reached the third stage which placed the seat of the soul in the brain. This step, however, was taken by the school of Hippocrates and corresponds to the advance made in anatomical knowledge, which led to an understanding of the important function of the brain. A Greek word for “mind,” phren —surviving in many modern terms,such as “phrenology,” etc.,—remains, however, as a witness to the earlier view, since it originally designated the part of the body below the diaphragm and takes us back, therefore, to the period when the seat of the intellect and the emotions was placed in the region of the liver. It is interesting to note that Aristotle, while recognising the important part played by the brain, still clung to the second stage of belief which placed the centre of soul-life in the heart. He presents a variety of interesting arguments for this view.[5] Plato,[6] however, in the generation before Aristotle, adopts a compromise in order to recognise all three organs. He assigns one soul which is immortal to the brain, which together with the heart, the seat of the higher mortal soul, controls the intellect and gives rise to the higher emotions, stimulating men to courage, to virtue, and to noble deeds, but he locates a third or appetitive soul below the diaphragm, with the liver as the controlling organ, which is the seat of the passions and of the sensual appetites.

Plato’s view is interesting as illustrative of the gradual decline which the liver was forced to endure in popular estimation. From being the seat of life, the centre of all intellectual functions and of all emotions, it is at first obliged to share this distinction with the heart, is then relegated to a still lower stage when the brain is accorded the first place, and finally sinks to the grade of an inferior organ, and is made the seat of anger, of the passions, of jealousy, and even of cowardice. To call a man “white-livered” became in Shakespearian usage an arrant coward, whereas in Babylonian speech it would designate the loftiest praise:—a man with a “white” soul. The modem popular usage still associating the chief qualities of man with the three organs—brain, heart, and liver—is well expressed in the advertisement of an English newspaper which commends itself to its readers by announcing that it is “all brain and heart, but no liver.”

We must go all the way back to Babylonian divination to find the liver enthroned in all its pristine glory. In truth to the Babylonian and Assyrian the liver spelled life.[7] Though even popular thought moved to some extent away from the primitive view which saw in the liver the entire soul, still the system of divination, perfected at a time when the primitive view was the prevailing one, retained its hold upon the popular imagination down to the latest period of Babylonian-Assyrian history; and accordingly, the inspection of the liver of the sacrificed animal, and of the liver alone, lies at the foundation of Babylonian-Assyrian divination and may be designated as the method of all others for determining what the gods had in mind.

To recapitulate the factors in the theory underlying Babylonian-Assyrian hepatoscopy—or liver divination,—the animal selected for sacrifice is identified with the god to whom it is offered. The soul of the animal is attuned to the soul of the god, becomes one with it. Therefore, if the signs on the liver of the sacrificial animal can be read, the mind of the god becomes clear. To read the deity’s mind is to know the future. Through the liver, therefore, we enter the workshop of the gods, can see them at work, forging future events and weaving the fabric of human fortunes. Strange as such reasoning may seem to us, let us remember that it still appealed to the learned and profound Plato, who in a significant passage[8] declares the liver to be a mirror in which the power of thought is reflected.

III

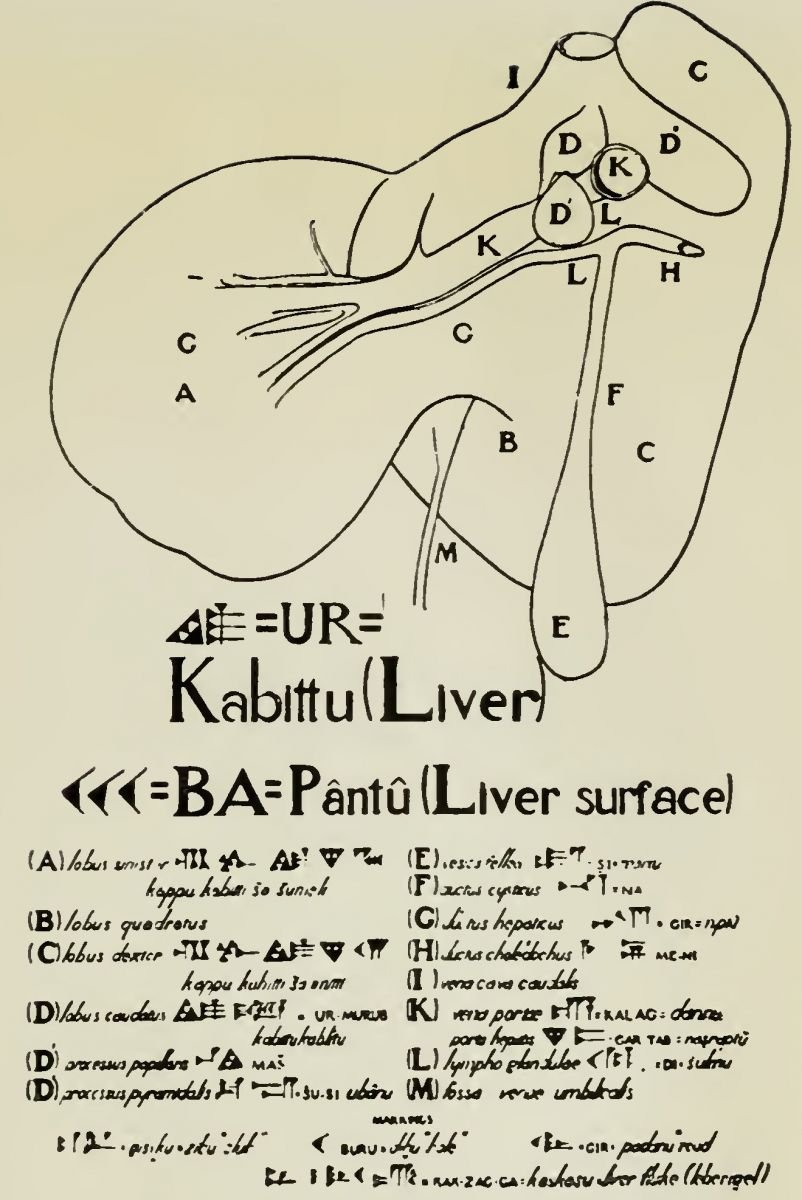

But how is the liver to be read? No one who has ever looked at a sheep’s liver—and it was invariably a sheep that was used in Baby Ionian-Assyrian divination—can fail to have been struck by its complicated appearance. In contrast with the heart, e.g., which is not only smaller but consists merely of a series of loops having no special marks to attract attention, the liver has many striking features. There is, first of all, the gall-bladder which lies on it and terminates in a long duct, known as the cystic duct. This duct connects in turn with a second duct, lying across the liver and known as the hepatic duct. From this duct smaller ducts pass out in various directions. Through these subsidiary ducts, gall is collected from various parts of the liver. Passing into the hepatic duct, and then through the cystic duct into the gall-bladder, it is there purified and prepared for further absorption. The lobes of the liver are also of striking appearance. The two lower ones—one on the right and one on the left—are sharply divided from one another, and the right lobe is further separated into two sections by the groove in which the gall-bladder lies.[9] The third and upper lobe, known as lobus pyramidalis,[10] is separated from the lower lobes by a narrow depression, still designated in modern anatomical nomenclature by a fanciful name, “the gate of the liver” (porta hepatis).[11]

Attached to this upper lobe are two appendices, a smaller one on the left, known as the processus papillaris, and a larger one on the right, having the shape of a finger and known as the processus pyramidalis. At the upper terminus of the liver, there protrudes the large hepatic vein (vena cava) through which the blood from the liver is carried to the heart. To these features must be added the fissures on the surface and the markings which appear on the livers of freshly slaughtered sheep—as well as of other animals. Varying with each specimen, they present, especially in the lower lobes, the appearance of a map with cross lines and curves. These markings are, in fact, merely the traces on the liver surface of the subsidiary ducts above referred to. They gradually fade out, but when the liver is in a fresh state they are striking in appearance. Not only do these markings differ in each specimen, but the other features—the gallbladder, the various ducts, the lobes and appendices —are never exactly alike in any two livers; they are as little alike as are the leaves of a tree.

The field thus offered for observation and careful inspection of the liver of the sacrificial animal was an extensive one; and it was this field that was thoroughly explored and cultivated by the priests whose special office it was to divine the future by means of the liver. The gall-bladder might in one instance be reduced in size, in another abnormally swollen, or it might be swollen on one side and not on the other. Again, it might be firmly attached to the liver surface, or hang loosely on it, or protrude beyond the liver, or not. The cystic duct might be long in some instances, and short in others; and the same possible variations would apply to the hepatic duct. The latter has a wavy appearance and the number and character of these waves differ considerably in different cases. So also the shapes and sizes of the lobes are subject to all kinds of variations; and even more significant would be the varying character of the two appendices attached to the upper lobes—the processus pyramidalis and the processus papillaris.

Finally, as has been suggested, the fissures and markings extend the scope of the signs to be noted almost indefinitely. To all these variations in the case of healthy livers must be added the phenomena due to pathological conditions. The diseases most common to men and animals in marshy districts like the Euphrates Valley primarily affect the liver. Liver diseases are said to be particularly common among sheep; the result is that the livers of freshly slaughtered specimens exhibit all manner of peculiarities, swellings, and contractions in the ducts and lobes as well as perforations on the liver surface known as “liver flukes,” due apparently to bacteriological action. It will be seen, therefore, that the opportunity offered to the Babylonian diviners for developing an elaborate system of interpretations of the signs to be observed was a generous one. Hundreds, nay thousands, of fragments in Ashurbana-pal’s library bear witness to the activity displayed by the priests in embracing this opportunity.

We have large collections of tablets more or less systematically arranged and grouped together into series,[12] in which all the possible variations in connection with each part of the liver are noted and the interpretations given. Thus, in the case of the gall-bladder, among the many signs enumerated we find such as whether the right or left side was sunk, whether the gall-bladder was full of gall, whether there was a fissure in the gall-bladder running from right to left or from left to right, whether the fissure was long or short. The shade of the colour of the gall was also taken into consideration, whether greenish or whitish or bluish. For the cystic duct entries are made in case it is long, reaching up to the hepatic duct, or appears to be short. The gall-bladder and the cystic and hepatic ducts—as also the lobes—were divided into sections—basis, middle, and head—and according as peculiar phenomena were observed in the one division or the other, the interpretation would vary. Thus, the basis, middle, or top of the cystic duct might be choked up or sunk in, or choked up and also sunk in, or choked up and exhibiting one or more fissures. In the case of the hepatic duct we find entries noting whether it is divided into two or more parts, whether between the divisions there are fissures or markings, whether it contains a gall-stone at the top, whether the duct appears raised or sunken, whether it is swollen, whether it contains white or dark fluid, and so ad infinitum. Included in the collections are long series of observations on the character of the depression between the upper lobe and the lower lobes, whether it appears narrow on the left or on the right side or on both sides, whether it is ruptured on the right side or left side, whether it is bent back “like a goat’s horn,” whether it is hard and firm on the left or the right side, whether it is defective on the one side or the other, whether it contains fissures “like the teeth of a saw,” and so on again through an almost endless and very monotonous list of signs.

The great vein of the liver (vena cava) is similarly treated, and here much depends upon the varying shape of the vein, whether it is separated from the liver, or partly separated, whether there is a marking above it or below it or whether it is surrounded by markings, whether its colour is black or green, whether it contains fissures, the colour of the fissures, and the like. The lower surface of the large finger-shaped appendix was fantastically designated as its “palace,” and note was taken whether the top, middle, or basis was tom away and whether the rent was on the right or the left side, or again whether the hind part of the appendix was torn, and in what section,—at the top, middle, or at the base. The relationship of one part of the liver to other parts also furnished a large number of variations which were entered in the collections of signs, and, lastly, the markings on the liver were subjected to a careful scrutiny and all kinds of variations registered. According to their shape, they were known as “weapons,” “paths,” or “feet.” Those resembling weapons were further fantastically compared to the weapons that formed symbols of the gods, while “paths” and “feet,” as will be evident, suggested all manner of associations of ideas that entered into the interpretation of the signs noted.[13]

The field of observation being almost boundless, it is evident that no collection of signs, however large, could exhaust the variations to be noted and the peculiarities that every specimen afforded. It was, however, the aim of the priests in making these collections to bring together in the case of each part of the liver as large a number of signs as possible so that, with the interpretations added, these collections might serve as handbooks to be consulted by priests, entrusted with this branch of priestly service. It is from these collections of signs with their interpretations, that we are able to reconstruct the system of liver divination devised by the uninterrupted activity of many successive generations of priests.

IV

The name given to the class of priests whose special function it was to divine the future was bāru , which means literally “inspector.” It corresponds to “seer,” but in the literal sense, as one who “looks” at something. That is, also, the original force of our term “seer,” which is a translation of a Hebrew term,[14] the equivalent of the Babylonian term bârû , denoting, like the latter, the power of divining through an “inspection” of some kind. The bârû, as the diviner through the liver—the “inspector” of the signs on the liver,—is therefore the prototype of the modern meat inspector, and, in passing, it may be noted that midway between the ancient and the modern bârû we find among the officials of Talmudi-cal or Rabbinical Judaism an official inspector of the organs of the animal killed for food, whose duty is to determine whether the animal is ritualistically “clean”; upon this examination depended whether or not the meat could be eaten. There can be no doubt that this ritualistic inspection is merely a modification of the ancient examination for purposes of divination, just as the hygienic or semi-hygienic aspects of the dietary laws in the Pentateuchal codes represent the superstructures erected on the foundations of primitive “taboos.”

The high antiquity to which divination through the liver can be traced back in the Euphrates Valley justifies the conclusion that the application of the term bârû to the “inspector” of the signs on the liver represents the oldest usage, and that the term was subsequently employed to designate other forms of divination, all of which, however, involved the scrutiny and interpretation of signs. So he who gazed at the heavens and read the signs to be noted there was also called a bârû and, similarly, the name was given to the priest who divined the future through noting the action of drops of oil poured in a basin of water, or through observing clouds or the flight of birds or the actions of animals, or who could interpret any other phenomenon which because of its unusual or striking character aroused attention. The term bârû in this way became the general term for “diviner,” whose function it was to interpret omens of all kinds.

In the days of Gudea the phrase “liver inspection” had acquired the technical sense of divining the future whereby that ruler determined the favourable moment for laying the foundations of a sacred edifice to his god Ningursu. Still earlier than Gudea, we find Sargon and Naram-Sin consulting a sheep’s liver before starting on a military expedition, before giving battle, on the occasion of an internal revolt, and before undertaking building operations. The evidence of the continuous employment of this method of divination is almost uninterrupted down to the end of the neo-Babylonian monarchy. We have tablets from the period of the first dynasty of Babylon and from the Cassite period, giving the results of examinations of the liver undertaken by the priests in connection with some important enterprise.[15] These were forwarded to the rulers as official reports, accompanied not infrequently by illustrative drawings. A large number of such reports have come down to us from the Assyrian period[16] which show that livers were consulted at the instance of the kings before treaties were made, before dispatching emissaries, before appointing officials to important posts, as well as in cases of illness of the king, of the king’s mother, or of any member of the royal household.

In the course of time there grew up also in connection with the inspection of livers an elaborate ceremonial. The officiating bârû had to wash and anoint himself in order to be ritually “pure” before approaching the gods. Special garments were donned for the ceremony. A prayer was offered to Shamash, or to Shamash and Adad, who were addressed as “lords of divination,” and in their names the inspection was invariably made. The question to which an answer was desired was specifically stated,— whether, or not, within the next one hundred days the enemy would advance to an attack; whether or not the sick person would recover; whether or not a treaty should be made; whether or not an official would be faithful to his charge, and the like. The sacrificial sheep had to be acceptable to the gods of the divination. It must be without blemish, and care had to be taken that in slaughtering it and in the examination of the liver no smallest misstep or error whatever should be made, else the entire rite would be vitiated. Prayers were offered for divine assistance to avoid all such errors. Then the examination was made, the signs all noted, and the conclusion drawn. A single inspection, it would appear, was regarded as conclusive if all the signs or a majority of them at least were favourable. If all the signs were unfavourable or so considerable a number as to leave doubtful the purpose and will of the gods, a second sheep was offered and the entire ceremony repeated, and if this, too, proved unfavourable, a third and final attempt would be made.

The last king of Babylonia, Nabonnedos (555539 B.C.), whose religious scrupulosity is one of his significant traits, shows how down to the advent of Cyrus, the method of ascertaining the will of the gods employed by Sargon and Gudea was still commonly resorted to. The king wishes to restore a temple to the moon-god at Harran and to carry back the images of the gods to their proper seats. In order to ascertain whether this is agreeable to Marduk, the chief deity, he consults the liver of a sheep and gives us the result of the examination, which proved to be favourable. On another occasion he proposes to make a certain symbol[17] of the sun-god and is anxious that it should be made in accordance with an ancient pattern. He has a model of the symbol made, places it before Shamash, and consults a liver in order to ascertain whether the god approves of the pious offering. To his surprise three times the signs turn out to be unfavourable.

The king is dismayed and concludes that the model was not a correct reproduction of the ancient symbol. He has another prepared and again calls upon the bârû to make an examination of a liver. This time the signs, which he furnishes in detail,[18] are favourable. In order, however, to make assurance doubly sure, possibly suspecting his priests of manipulating the observations, he tells us that he sought among the archives for the result of a liver inspection on a former occasion when the subsequent events proved the correctness of the favourable decision; then placing the two series of omens side by side, he convinced himself that it was safe to proceed with the making of the symbol. The evident sincerity and conscientiousness of the king should make us charitably inclined to his superstitious regard for the primitive rite, which, as the official cult, had all the authority of a time-honoured faith and custom.

Another indication of the vast importance attached to liver inspection is to be discovered in the care with which ancient records thereof were preserved and handed down as guides for later generations of priests. In the foregoing enumeration of liver omens, there are frequent references to the fact that a particular sign had been observed in the consultation of a liver, undertaken on behalf of some important personage. Thus, we are told that a certain sign was the one noted at a time when a ruler of Kish, known as Urumush, was killed by his courtiers in an uprising.[19] Another sign is entered as having been observed at a liver inspection made on behalf of Ibe-Sin, the last king of the Ur dynasty (ca., 2200 B.C .).[20] A number of omens are associated with Gilgamesh,[21] the semi-mythical hero of the Babylonian epic, indicating that underlying the myth there is a basis of historical tradition. In these associations Gilgamesh is termed a “mighty king.” Such references lead to the conclusion that, because of the importance which the traditions concerning significant personages assumed, the omens which accompanied certain events in their careers were embodied in the collections, and it may-well be that special collections of such historical omens were made by the priests.

We know in fact of one such collection of omens referring to Sargon and Naram-Sin, extracted from chronicles of their reigns,[22] in which the results of the liver investigations made at important epochs in their career were recorded. These extracts, whereof we are fortunate enough to possess fragments, were compiled, not from any historical motives but to serve as guides for the bârû priests and also as school exercises in training the young aspirants to the priesthood for their future task. The collection, furthermore, illustrates an important principle in the method adopted for interpreting the signs; it was argued, that if on a certain occasion, let us say before an attack on the ancient enemy, Elam, the gall-bladder, the various ducts and lobes, and markings showed certain features, and the result of the battle was a victory for Sargon, the proof was furnished de facto that these were favourable signs. On the natural though illogical principle, “once favourable, always favourable,” it served also in case of a recurrence of the signs to prognosticate a favourable disposition on the part of the gods invoked. The significant point was not so much the particular favourable event that ensued, but the fact that it was favourable. On this same principle we have as a second fundamental canon in liver divination, “favourable for one purpose, favourable for any other.” The signs noted being favourable, the application depended solely upon the nature of the inquiry and the conditions suggested by the inquiry.

But while actual experience thus constituted an important element in the system of interpretation, one can detect other factors at work in leading to favourable or unfavourable interpretations of a sign, or group of signs. Among these factors the association of ideas stands, perhaps, in the forefront. In common with all nations of antiquity, the Babylonians regarded the right side as lucky, and the left as unlucky. Applying this to the liver, a particular sign on the right side of the gall-bladder, or of one of the ducts, or lobes, or on one of the appendices to the upper lobe, was interpreted as referring to Babylonia or Assyria, to the king, or to his army, or to his household, or to the country in general; while the same sign on the left side referred to the enemy. A good sign on the right side was, therefore, favourable to the inquirer; as was also a bad sign on the left, because what is unfavourable to an enemy is favourable to one’s self. On the other hand, a good sign on the left side or a bad sign on the right side was just as distinctly unfavourable.

But the question may here be properly asked—what constituted good or bad signs? The natural association of ideas in many cases suggested an answer. Thus, e.g., the enlargement of any part of the liver was, by this association, regarded as pointing to an expansion of power, whereas contraction would mean a diminution thereof. A large gall-bladder would thus be a favourable symptom, but a distinction was made: if the enlargement was on the left side, the sign would be favourable to the enemy, if on the right side, favourable to the inquirer. Again, in the case of the gall-bladder, the left side is sometimes firmly attached to the liver while the right side hangs loose, or vice versa. The tight hold on the liver indicated a firm grasp of the enemy. Hence, if the left side was firmly attached, it indicated that the enemy would be in your grasp; whereas if it was the right side, the enemy would hold you in his grasp, and the sign would thus be unfavourable. This principle was applied to other parts of the liver, where firmness would be associated with strength, and with a tight grasp on the enemy, while a flabby character or loose adhesion would mean the reverse:—weakness and disaster. Here again, should the firmness or flabbiness be limited to one side, the right or the left would be applied to yourself or to the enemy respectively.

Considerable attention was paid to the shape and appearance of the peculiar finger-shaped appendix[23] which hangs from the upper lobe, and which was in fact called by the Babylonians the “finger of the liver.”[24] It has two sides, an inner, broad surface which, as we have seen, was called the “palace,” and an outer side, designated by the Babylonian bârû priests as the “rear” side. By the same association of ideas which we have already noted, a marking on the right side of the “palace” indicated that the enemy would invade the land; a marking on the left side that the king’s army would invade the enemy’s land. The appendix, like the gall-bladder, lobes, and ducts, being divided into three sections, a marking at the base was regarded as favourable to the questioner, because the base represented the enemy. A marking at the top was unfavourable because, again by the association of ideas, the top represented the king or one’s own country. The relationship of the larger appendix to the smaller[25] was also regarded as important. In the event of the larger being abnormally small and the smaller abnormally large, the sign was interpreted as a reversal of normal conditions, so that the small would be great and the weak would be strong, while the large would become small and the strong become weak. Specific interpretations of such signs in given instances are stated to be, that the son will be more powerful than the father, that the servant will be superior to the master, or that the maid will become the mistress—possibly hints that domestic troubles are not a modem invention, but that they vexed the souls of even Babylonian housewives, and that the servant-girl question ascends to an antiquity so remote as to be time-honoured and respectable.

This same association of ideas was extended in other directions, and applied to the terms long and short. A long cystic or hepatic duct pointed to long life or to a long reign, a short duct to a short life or to a short reign. It has already been pointed out that the markings on the liver were frequently compared to weapons. Indeed this comparison was of all the most frequent, and, according to the shapes of the weapons, they were associated with Ishtar, Enlil, Ninib, Sin, and other deities.[26] By a further extension of this association, an Ishtar “weapon” or marking was interpreted as indicating the protection or the hostility of this goddess, a Ninib “weapon” was associated with its namesake, and so on, through the list. Thus the system developed; and it can be easily seen how a few basic phases of association of ideas can be extended to endless ramifications. This may be best illustrated by a few examples.

V

The collection of omens illustrative of events in the reigns of Sargon and Naram-Sin begins as follows[27]:

If the gall-bladder spreads over the liver surface—an omen of Sargon, who on the basis of this omen proceeded against Elam, subjugated the Elamites, made an enclosure around them, and cut off their supplies.

We must of course assume that these details represent extracts from a chronicle of what actually happened in the campaign against Elam, but arguing backwards from the event to the sign, it is reasonable to suppose that the priests saw in the extension of the gallbladder the grounds for the favourable character of the sign. The picture of the gall-bladder encompassing the liver surface would further suggest the enclosure around the enemy, shutting him in.

Another sign in this collection reads:

If the liver surface, exclusive of the gall-bladder and the “finger of the liver,”[28] is shaped like the lid of a pot,[29] on the right side of the liver a “weapon” is interposed, and on the left side and in front there are seven fissures—an omen of Sargon. On the basis of this omen the inhabitants of the whole land rebelled against him, encompassed him in Agade, but Sargon went forth, defeated them, accomplished their overthrow, humbled their great host, captured them together with their possessions, and devoted [the booty] to Ishtar.

In this case it is evident that the seven fissures— seven being a large round number—suggested a general disruption of the empire; but a marking associated with a weapon being interposed on the right side would naturally be regarded as pointing to a successful check of the uprising, while the circumstance of the liver being otherwise well-rounded and smooth was regarded as a sign of the ultimate disappearance of the difficulties with which Sargon found himself encumbered. The chief import, however, of the omen, it must be borne in mind, is that the subsequent events proved the signs in question to have been favourable; but at the same time it was the purpose of the priests, as is suggested above, in compiling, from the official chronicles, a series of omens dating from the reigns of Sargon and Naram-Sin, to preserve them as a guide for the future. The great name of King Sargon, whose fame as a successful conqueror gave rise to legends of his birth and origin, was assuredly one to conjure with. If on any occasion the examination of a liver revealed a “Sargon” sign, there could be no mistaking its import. Events showed what it meant and signs given to the great king—the favourite of the gods—would, necessarily, be trustworthy guides.

These two factors, records,—or recollections of events following upon signs observed on specific occasions, and a natural, or artificial, association of ideas,—control the large collections of “liver” omens, which in the course of time were stored in the temples through the activity of priests. With the help of these collections, as guides and reference-books, all that was necessary was to observe every possible sign on the liver; note them down; refer them to the collection which would furnish the favourable or unfavourable interpretation; register these interpretations; and then, from a complete survey, draw a conclusion, if haply one could be formed.

The interpretations themselves in these collections relate, almost exclusively, to the general welfare and not to individual needs or desires. They refer to warfare; to victory or defeat; to uprisings and devastations, pestilence and crops. Individuals are not infrequently referred to, but the reference is limited to the ruler or to members of his household, under the ancient view taken of royalty,[30] that what happens to the king and his household affects the fortunes of the country for good or evil. This, of itself, does not exclude the possibility that private individuals consulted the bârû priests, and had liver examinations made on their own behalf. It must be remembered that our material consists of official records; but it may be said in general that the gods were supposed to concern themselves with public affairs only, and not with the needs of individuals.

This is in keeping with what we know generally of Babylonian-Assyrian culture, which reveals the weak-I ness of the factor of individualism. The country and the community were all in all; the individual counted for little, in striking contrast, e.g., to Greek culture, where the individual almost overshadows the community. The circumstance that, in the large collections of omens, the interpretations deal with affairs of public and general import, thus turns out to be significant; and while, as we have seen, the important feature for those who resorted to divination was merely to ascertain whether the interpretation was favourable or unfavourable, the interpretations themselves in the collections are always explicit in referring to a specific prognostication as favourable, or unfavourable.

The attempt to follow in detail the association of ideas which led to each specific interpretation would be a hopeless and also a futile task. We may well content ourselves with a recognition of the main factors involved in this association of ideas as above outlined. Thus, we can understand that a fissure on the right side of the gall-bladder should point to some disaster for the army, and a fissure on the left to disaster for the enemy’s army; or that a fissure on both right and left should prognosticate general defection; but why, where there are two ruptures at the point of the gall-bladder, a short one on the right side should indicate that the enemy will destroy the produce of the land, but if the left one is short the enemy’s produce will be destroyed, is not apparent, except on the basis of a most artificial association of ideas. We can understand why a double-waved hepatic duct, with the upper part defective, should point to a destruction of the king (the upper part representing, like the right side, the king and his army), and why, if the lower part is defective, the enemy’s army will be destroyed (the lower part, like the left side, representing the enemy); but any ordinary association of ideas fails to account for the prediction that a rupture between the two waves of the duct means specifically that a pestilence will rage, or that there will be an inundation and universal devastation. It seems reasonable to assume that many of these specific deductions rest, as in the case of the genuinely historical omens, upon actual experience, that on a certain occasion, when the sign in question was observed at a liver inspection, a pestilence followed, or an inundation, accompanied by great destruction, took place.

The priests would naturally take note of all events of an unusual character which followed upon any examination, and record them in connection with the sign or signs; and it is easy to see how, in the course of time, an extensive series of such specific interpretations would have been gathered, resting not upon any association of ideas between a sign and a prognostication, but upon the rule of post hoc , proper hoc. In such cases, the guidance for the priests would be restricted, just as in the case of historical omens, to an indication whether the interpretation was favourable or unfavourable. If favourable, the repetition of the sign would likewise be favourable and could apply to any situation or to any inquiry, quite irrespective of the specific interpretation entered in the collections. The scope would be still further enlarged by logical deductions made from an actual record of what happened after the appearance of a certain sign or series of signs observed on a single former occasion. Thus, if a specific sign on the right side of a part of the liver was^ as a favourable symptom, followed by good crops, it was possible to add an entry that if the same sign occurred on the left side, it would point to bad crops.

In all these various ways, and in others that need not be indicated, the collections would, in the course of ages, grow to colossal proportions. Each important temple would collect its own series, and the ambition of the priests would be to make these series as complete as possible, so as to provide for every possible contingency. A table of contents which we fortunately possess,[31] of two such series of omen collections, enables us to estimate their size. The tables furnish the opening lines of each of the fourteen and seventeen tablets of which the series respectively consisted. In one case the number of lines on each tablet is also indicated, from which we may gather that the series consisted of about fifteen hundred lines, and, since each line contained some sign noted together with the interpretation, it follows that we have not less than fifteen hundred different signs in this one series.

Considering that we have remains, or references, to over a dozen series of these liver omens in the preserved portions of Ashurbanapal’s library, it is safe to say that the recorded signs and interpretations mount high into the thousands.

A few specimens from these collections will suffice to illustrate their character[32]:

If the cystic duct is long, the days of the ruler will be long.

If the cystic duct is long, and in the middle there is an extended subsidiary duct, the days of the ruler will soon end.

If the base of cystic duct is long, and there is a fissure on the right side, the enemy will maintain his demand against the ruler, or the enemy will bring glory from out of the land.[33]

If the base of the cystic duct is long, and there is a fissure on the left side, the ruler will maintain his demand against the enemy, or my army will bring glory out of the enemy’s land.

If the base of the cystic duct is long, lying to the right of the hepatic duct, the gods will come to the aid of the enemy’s army, the enemy will kill me in warfare.

If the base of the cystic duct is long, lying to the left of the hepatic duct, the gods will come to the aid of my army, and I shall kill the enemy in warfare.

In the same way we have a long series of omens detailing the various possibilities in connection with fissures in the gall-bladder[34]:

If the gall-bladder is split from right to left, and the split portion hangs loose, thy power will vanquish the approaching enemy.

If the gall-bladder is split from left to right, and the split portion hangs loose, the weapon of the enemy will prevail.

If the gall-bladder is split from right to left, and the split portion is firm, thine army will not prevail in spite of its power.

If the gall-bladder is split from left to right, and the split portion is firm, the enemy’s army will not prevail, in spite of its power.

If the gall-bladder is split from right to left, and there is a gallstone at the top of the fissure, thy general will capture the enemy.

If the gall-bladder is split from left to right, and there is a gallstone at the top of the fissure, the general of the enemy will capture thee.

Among the many signs noted in the case of the hepatic duct in the collection, we find the following[35]:

If the hepatic duct is twofold[36] , and between the two parts there is a marking,[37] Nergal[38] will rage, Adad[39] will cause overflow, Enlil’s word will cause general destruction.

If the hepatic duct is twofold, and between the two parts there is a “weapon”[40], visible above,[41] the enemy will advance and destroy my army.

If the hepatic duct is twofold, and between the two parts there is a “weapon,” visible below,[42] my army will advance and destroy the enemy.

If the hepatic duct is twofold, and between the two parts there is a “weapon,” visible on the right side,[43] march of the enemy’s army against the land.

If the hepatic duct is doubled, and between the two parts there is a “weapon,” visible on the left side, march of my army against the enemy’s land.

Out of an even larger number of symptoms[44] associated with the depression between the upper and the lower lobes, known as “the liver-gate,” a few extracts will suffice:

If the liver-gate is long on the right side and short on the left, joy of my army.

If the liver-gate is long on the left side and short on the right, joy of the enemy’s army.

If the liver-gate is crushed on the right side and torn away,[45] the ruler’s army will be in terror.

If the liver-gate is crushed on the left side and torn away, the enemy’s army will be in terror.

If the liver-gate is tom away on the right side, thine army will go into captivity.

If the liver-gate is torn away on the left side, the enemy’s army will go into captivity.

If, in the curvature[46] of the liver-gate, there are fissures to the right of the hepatic duct, the enemy will advance to my dwelling-place.

If, in the curvature of the liver-gate, there are fissures to the left of the hepatic duct, I will advance against the enemy’s army.

If, in the curvature of the liver-gate, there is one fissure to the right of the hepatic duct, thine army will not prevail, despite its power.

If, in the curvature of the liver-gate, there is one fissure to the left of the hepatic duct, the enemy’s army will not prevail, despite its power.

Similarly, two fissures mean “captivity,” three fissures “enclosure,” and four fissures “devastation” —applying to the enemy or to the king’s side according to the appearance of the fissures to the right or to the left of the hepatic duct. Lastly, a brief extract from a text dealing with symptoms connected with the finger shaped appendix[47]:

If the finger is shaped like a crescent, the omen of Urumush, the king whom his servants put to death in his palace.[48]

If the finger is shaped like a lion’s head, the servants of the ruler will oppose him.

If the finger is shaped like a lion’s ear, the ruler will be without a rival.

If the finger is shaped like a lion’s ear, and split at the top, the gods will desert thy army at the boundary.[49]

If the finger is shaped like an ox’s tongue, the generals of the ruler will be rebellious.

If the finger is shaped like a sheep’s head, the ruler will exercise power.

If half of the finger is formed like a goat’s horn, the ruler will be enraged against his land.

If half of the finger is formed like a goat’s horn, and the top of it[50] is split, a man’s protecting spirit will leave him.

If the finger is shaped like a dog’s tongue, a god[51] will destroy.

If the finger is shaped like a serpent’s head, the ruler will be without a rival.

In the official reports of liver examinations forwarded to the rulers, and at times embodied in their annals, all the signs, as observed, were recorded, and the interpretations added as quotations from these omen collections. It thus happened that, in many cases, these interpretations had no direct bearing on the character of the inquiry, but the interpretation showed whether or not the sign was favourable, which was the chief concern of both priests and applicants. On the basis of the extracts, therefore, a decision was rendered, and often a summary given at the end of the reports, indicating the number of favourable and unfavourable signs.The number of signs recorded on the liver varied considerably. Every part of the liver was scrutinised, but frequently no special marks were found on one part or the other. The minimum, however, of signs recorded, in any known instance, appears to have been ten, and from this number upward we have as many as fifteen and even twenty variations.

To give an example from the days of the Assyrian empire, we find, in response to a question put to a bârû priest whether or not an uprising that had taken place would be successful, the following report of the results of the examination of the liver of a sacrificial sheep[52]:

The cystic duct is normal; the hepatic duct double, and if the left part of the hepatic duct lies over the light part of the hepatic duct, the weapons of the enemy will prevail over the weapons of the ruler.

The hepatic vein is not normal—this means siege.

There is a depression to the right of the cystic duct[53]—overthrow of my army.

The left side of the gall-bladder is firm, through thee,[54]— conquest of the enemy. The “finger" and the papillary appendix[55] are normal.

The lower part of the liver[56] to the right is crushed—the leader will be crushed, or there will be confusion in my army.[57]

The upper part is loose.

The curvature over the lower point[58] is swollen, and the basis of the upper lobe is loose.

The liver “fluke”[59] is destroyed, the network of the markings consists of fourteen [meshes], the inner parts of the sheep are otherwise normal.

The “inspector” then adds as a summary that five of the signs are unfavourable, specifying the five he has in mind, and closes with the decision “it is unfavourable.” The examination thus showed that the gods were not favourable to the king’s natural desire to quell the rebellion, and that more trouble was to be expected.

As a second example of the recorded result of a liver examination let us take a report incorporated by king Nabonnedos in his annals, on the occasion of his consulting the priests in order to ascertain whether or not the deities approved of the king’s purpose to make a symbol of the sun-god as a pious offering.[60]

The first result, though favourable, did not quite satisfy the king; it showed the following signs, together with the interpretations as furnished by the omen collections[61]:

The cystic duct is long—the days of the ruler will be long.

The compass of the hepatic duct is short—the path of man will be protected by his god;[62] god will furnish nourishment to man, or waters will be increased.[63]

The lymphatic gland is normal—good luck.

The lower part of the gall-bladder is firm on the right side, torn off on the left—the position of my army will be strong, the position of the enemy’s army endangered. The gall-bladder is crushed on the left side—the army of the enemy will be annihilated, the army of the ruler will gain in power.

The “finger” is well preserved—things will go well for the sacrificer[64], and he will enjoy a long life.

The papillary appendix is broad—happiness.

The upper surface[65] wobbles[66]—subjection, the man will prevail in court against his opponent.

The lower part of the “finger” is loose—my army will gain in power.

The network of markings consists of fourteen well developed meshes—my hands will prevail in the midst of my powerful army.

Although, for reasons indicated, the interpretations have no bearing whatsoever on the inquiry, they are all favourable, and the king might have been satisfied with the result. In order, however, to remove all possible doubt as to the correctness of the conclusions, he selected from the archives a series of signs, noted on a former occasion, when the subsequent events proved that the signs were favourable, and compared the two lists.

This second series reads as follows:

The cystic duct is long,—the days of the ruler will be long.

The hepatic duct is double on the right,—the gods will assist.

The lymphatic gland is well formed, the lower part firm— peaceful habitations.

The hepatic duct is bent to the right of the gall-bladder, the gall-bladder itself normal—the army will be successful and return in safety.

The gall-bladder is long,—the days of the ruler will be long.

The left side of the gall-bladder is firm,—through thee, destruction of the enemy.

There is a “weapon” in the middle of the back surface of the “finger” with downward curve,[67]—the weapon of Ishtar will grant me security, the attack of the enemy will be repulsed.[68]

The upper part of the hind surface of the liver[69] protrudes to the right, and a liver fluke has bored its way into the middle,— the protector of my lord will overthrow the army of the enemy by his power. The lower point[70] rides over the ditch[71],—the protection of (his) god[72] will be over the man. The angry god will become reconciled with man.

The signs recorded in the two series are not the same throughout, but there are enough points of agreement to reassure the king that the decision of the priests in the case of the first series was correct; and, what is equally to the point, there are no signs and interpretations in the second series that contradiet the first. The king, no doubt, was anxious to have the judgment of his “inspector” confirmed, and rested content, therefore, with a proof that might possibly not have appealed to a spirit more critically disposed.

VI

Childish as all these superstitious rites may appear to us, hepatoscopy had at least one important result in Babylonia. It led to a genuine study of the anatomy of the liver; and in view of the antiquity to which the observation and nomenclature of the various parts of the liver may be traced, there can be small doubt that to the bârû priests belongs the credit of having originated the study of anatomy[73]; just as their associates, the astrologers of Babylonia, also known as bârû, i.e., “inspectors,” of the heavens, laid the elementary foundations of astronomy, though, as we shall see, astronomy worthy of the name did not develop in the Euphrates Valley until a very late period.

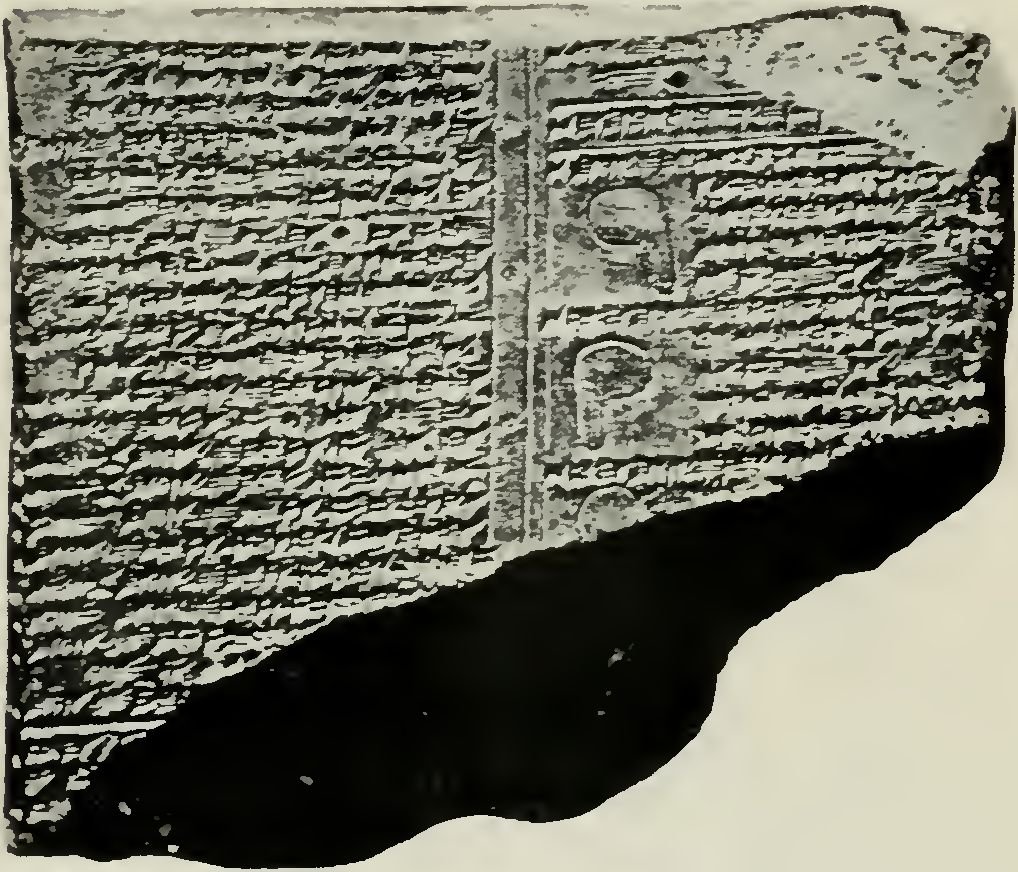

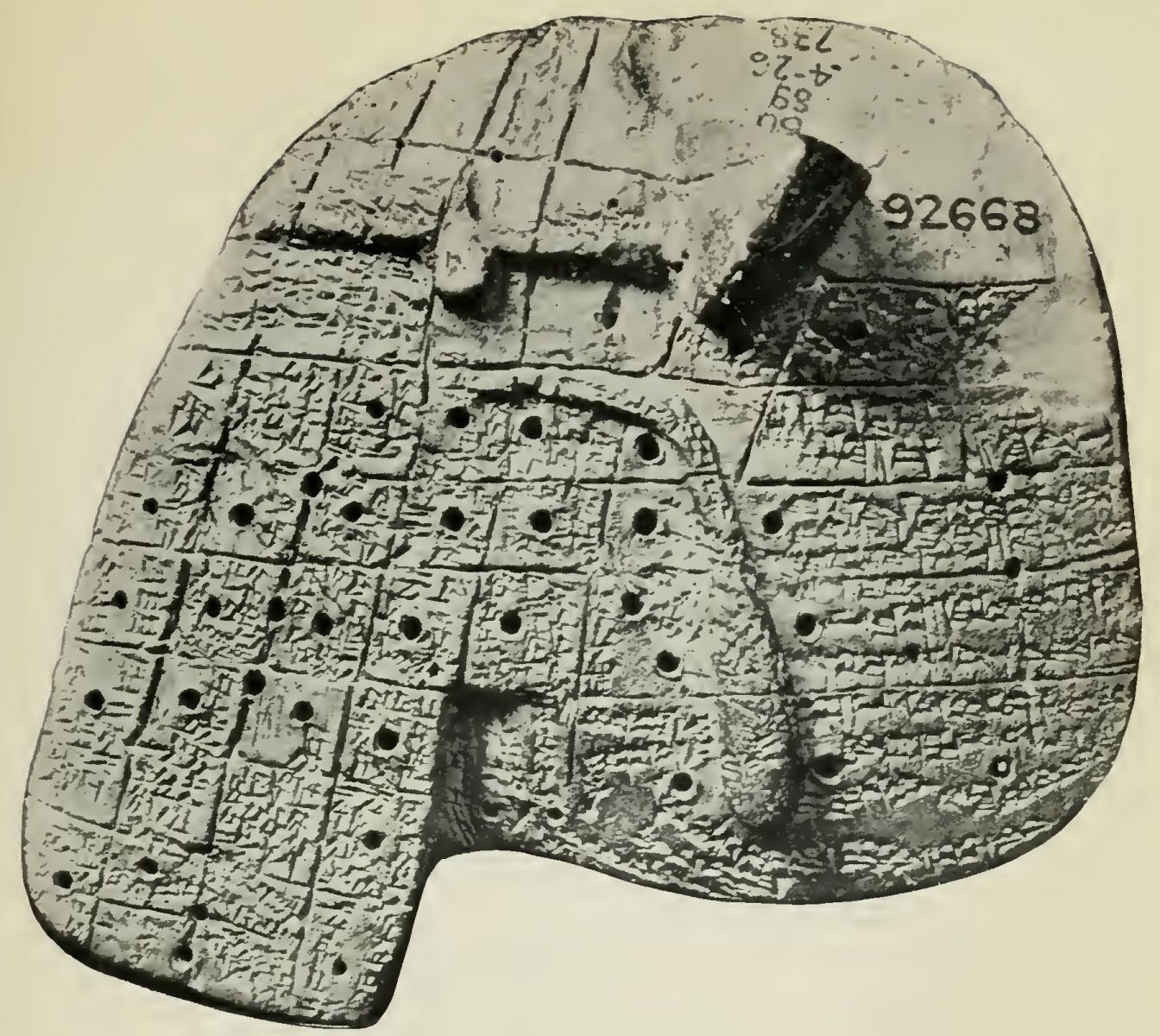

In another respect the study of the liver divination in Babylonia and Assyria is fraught with significance. Through it, a definite link is established between the ancient civilisations of the East and those of the West. This primitive process of divining the future, gradually elaborated into a complicated system, spread far and wide through the influence shed on the ancient world by the Euphratean culture. For centuries, it must be borne in mind, the study of hepatoscopy was carried on in the schools attached to the temples of Babylonia and Assyria, the collections made by the priests serving the double purpose of handbooks for practical use, and text-books for instructing pupils in training for the priesthood. From the remote days of Hammurapi there has come down to us an eloquent witness to the prominence occupied by hepatoscopy in the religious life of Babylonia, in the form of a clay model of a sheep’s liver[74] whereon the various divisions are carefully indicated, and in addition is covered with interpretations, applicable to signs noted in every portion of the organ. This model was unquestionably an object-lesson employed in a Babylonian temple school—probably in the very one attached to Marduk’s temple in Babylon itself[75]—to illustrate the method of divination and to explain the principles underlying the interpretation of the signs.

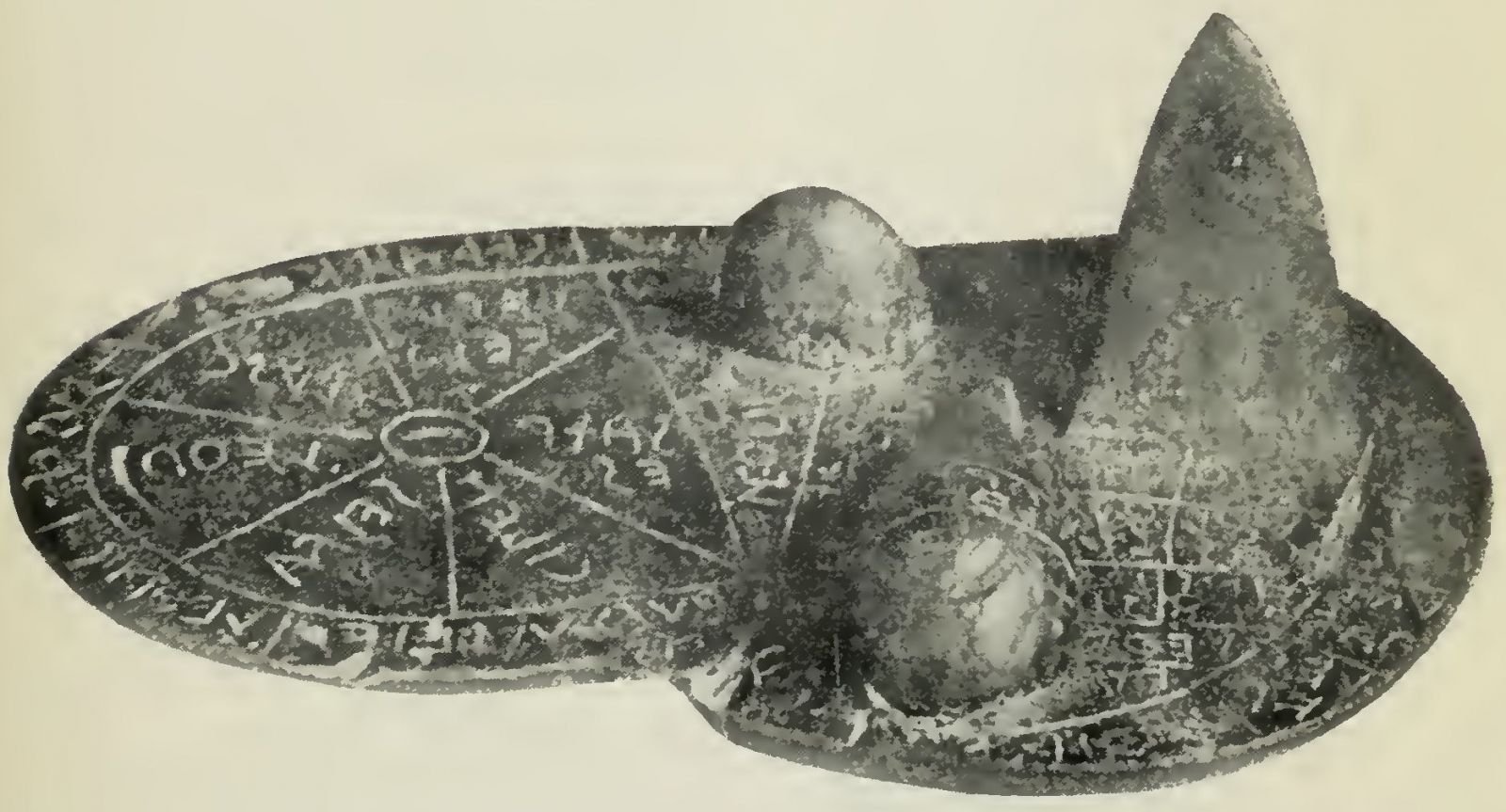

Similar models have quite recently been found in one of the centres of Hittite settlements at Boghaz-Kevi, and in view of the close relationship between the Hittites and the Babylonians, which can now be traced to the threshold of the third millennium before our era, there can be no doubt that the Babylonian system of hepatoscopy was carried far into the interior of Asia Minor. Babylonian-Assyrian hepatoscopy also furnishes a strong support for the hypothesis—probable on other grounds—which connects the Etruscan culture with that of the Euphrates Valley. Among the Etruscans we likewise find liver divination not only occupying an important position in the official cult, but becoming a part of it. As a companion piece to the Babylonian model of a sheep’s liver, we have a bronze model,[76] found about thirty years ago near Piacenza in Italy, which, covered with Etruscan characters, shows almost the same general design as the Babylonian model. This Etruscan model, dating probably from the third century B.C., but taking us back to a prototype that may be considerably older, served precisely the same purpose as its Babylonian counterpart: namely, to explain liver divination to the young haruspices of Etruria. The importance of this form of divination is illustrated by other Etruscan antiquities, such as the tomb of an haruspex, who holds in his left hand a liver as the sign-manual of his profession.[77]

Through the Etruscans hepatoscopy came to the Romans, and it is significant that down through the days of the Roman Republic the official augurs were generally Etruscans, as Cicero[78] and other writers expressly tell us. The references to liver divination are numerous in Latin writers, and although the term used by them is a more general one, exta ,—usually rendered “entrails,”—when we come to examine the passages,[79] we find, in almost all cases, the omen specified is a sign noted on the liver of a sacrificial animal. So Livy, Valerius Maximus, Pliny, and Plutarch unite in recording that when the omens were taken shortly before the death of Marcellus, during the war against Hannibal, the liver of the sacrificial animal had no processus pyramidalis,[80] which was regarded as an unfavourable sign, presaging the death of the Roman general. Pliny[81] specifies a large number of historical occasions when forecasts were made by the augurs, and almost all his illustrations are concerned with signs observed on the liver.

The same is the case with the numerous references to divination through sacrificial animals found in Greek writers; for the Greeks and Romans alike resorted to this form of divination on all occasions. In Greek, too, the term applied to such divination is a general one, hiera or hiereia , the “sacred parts,” but the specific examples in every instance deal with signs on the liver.[82] Thus, e.g., in the Electra of Euripides,[83] Ægisthos, when surprised by Orestes, is represented in the act of examining the liver of an ox sacrificed on a festive occasion. Holding the liver in his hand, Ægisthos observes that “there was no lobe,[84] and that the gate[85] and the gall-bladder portended evil.” While Ægisthos is thus occupied, Orestes steals upon him from behind and deals the fatal blow. Æschylus, in the eloquent passage in which the Chorus describes the many benefits conferred on mankind by the unhappy Prometheus, ascribes to the Titan the art also of divination, but while using the general term, the liver is specified:

The smoothness of the entrails, and what the colour is, whether portending good fortune, and the multi-coloured well-formed gallbladder.[86]

Whether or not the Greeks adopted this system of hepatoscopy through the influence likewise of the Etruscans, or whether or not it was due to more direct contact with Babylonian-Assyrian culture is an open question. The eastern origin of the Etruscans is now generally admitted, and it may well be that in the course of their migration westward they came in contact with settlements in Greece; but on the other hand, the close affiliation between Greece and Asia Minor[87] furnishes a stronger presumption in favour of the more direct contact with the Babylonian system through its spread among Hittite settlements.

VII

Liver divination, however, in thus passing to the Greeks and Romans, underwent an important modification which was destined eventually to bring the practice into disrepute. It will be recalled that the entire system of hepatoscopy rested on the belief that the liver was the seat of the soul, and that this theoretical basis was consistently maintained in Babylonia and Assyria throughout all periods of the history of these two states. Although there are indications in phrases used in the penitential hymns and lamentations of Babylonia and Assyria that the heart was associated with the liver,[88] just as the Hebrews combined the liver and heart in their later religious poetry to cover the emotions and the intellect,[89] the pre-eminent position accorded to the liver as the seat of all soul life, the source of intellectual activity and of all emotions—good and bad—was not seriously affected by any advance in knowledge that may have led to a better recognition of the functions of the heart.

The existence of an elaborate system of divination, based upon primitive theory, acted, with the Babylonians, as a firm bulwark against the introduction of any rival theory. Not so, however, among the Romans, whose augurs took what seemed an innocent and logical step, in order to bring the system of divination into accord with more advanced anatomy, by adding to the examination of the liver that of the heart, as being likewise an organ through which an insight could be obtained into the soul of the animal, and hence into that of the god to whom it was sacrificed. Pliny has an interesting passage in his Natural History in which he specifies the occasion when, for the first time, the heart in addition to the liver of the sacrificial animal was inspected to secure an omen.[90] The implication in the passage of Pliny is that prior to this date, which corresponds to c. 274 B.C., the liver alone was used.

Liver and heart continued to be, from this time on, the chief organs inspected, but occasionally the lungs also were examined, and even the spleen and the kidneys. Owing to the growing habit of inspecting other organs beside the liver, it became customary to speak of consulting the exta —a term which included all these organs. Similarly, we may conclude from the use of the terms splangchna (“entrails”) and hiera (“sacred parts”) in Greek writers, when referring to divination through the sacrificial animal, that among the Greeks also, who as little as the Romans were restrained by any force of ancient tradition, the basis on which hepatoscopy rested was shifted, in deference to a more scientific theory of anatomy which dethroned the liver from its position in primitive and non-scientific beliefs. This step, though apparently progressive, was fatal to the rite, for in abandoning the belief that the liver was sole seat of the soul, the necessity for inspecting it in order to divine the future was lost. There could be but one claimant as the legitimate organ of divination. If the soul were not in the liver but in the heart, then the heart should have been inspected, but to take both the liver and the heart, and to add to these even the lungs and other organs was to convert the entire rite into a groundless superstition—a survival in practice, based on an outgrown belief.

It is significant that this step was not taken by the Babylonians or Assyrians nor, so far as we know, by the ancient Etruscans, but only by the Romans and the Greeks. That they did so may be taken as an additional indication that hepatoscopy among them was an importation, and not an indigenous growth. As a borrowed practice, the Greeks and Romans felt no pressure of tradition which in Babylonia kept the system of liver interpretation intact down to the latest days. A borrowed rite is always more liable to modification than one that is indigenous, as it were, and attached to the very soil; thus it happens that, under foreign influences, divination through the liver, resting upon deductions from a primitive belief persistently maintained, degenerates into a foolish superstition without reason. It is also an observation that has many parallels in the history of religion:—a borrowed rite is always more liable to abuse. It is not, therefore, surprising to find that the “inspection” of an animal for purposes of divination degenerated still further among Greeks and Romans into wilful deceit and trickery.

Frontinus[91] and Polyaenus[92] tell us of the way in which the “inspectors” of later days had recourse to base tricks to deceive the masses. They tell, for instance, of a certain augur, who, desirous of obtaining an omen that would encourage the army in a battle near at hand, wrote the words, “victory of the king,” backwards on the palm of his hand, and then, having pressed the smooth surface of the sacrificial liver against his palm, held aloft to the astonished gaze of the multitude the organ bearing the miraculous omen.[93] The augur’s name is given as Soudinos “the Chaldean,” but this epithet had become at this time, for reasons to be set forth in the next lecture, generic for soothsayers and tricksters, indiscriminately, without any implied reference to nationality. Hence Soudinos , who may very well have been a Greek, is called “the Chaldean.”

Whatever the deficiencies of the Babylonian-Assyrian “inspectors” may have been, it must be allowed, from the knowledge transmitted to us, that down to the end of the neo-Babylonian empire they acted fairly, honestly, and conscientiously. The collections of omens and the official reports show that they by no means flattered their royal masters by favourable omens. It would have been, indeed, hazardous to do so; but whatever their motives, the fact remains that in the recorded liver examinations we find unfavourable conclusions quite as frequently as favourable. In a large number of reports delivered by the priests there seems nothing, so long as the religion itself held sway, to warrant a suspicion of trickery or fraud of any kind. At most, we may possibly here and there detect a not unnatural eagerness on the part of a diviner to justify his conclusion, or to tone down a highly inauspicious prognostication.

With the decline of faith in the ancient gods and goddesses, which sets in after the advent of Cyrus (539 B.C.), leaving in its wake, as we have seen,[94] anew and much more advanced and more spiritual religion, a different spirit is spread abroad. Contact with Greek culture also proved another serious blow to the time-honoured religious system. An era of degeneration followed in the Euphrates Valley, which is responsible for the disrepute into which the term “Chaldean” now fell.[95] The old bârû priests, the “inspectors” of livers and the “inspectors” of the heavens, became the tools of rulers whose interest was to keep alive the superstitions of the past. An end, sad indeed for a religious rite which had been so carefully cherished and developed into an elaborate system by generations of priests, who also took, it must be remembered, a large and honourable share in rearing the imposing structure of Euphratean civilisation.

VIII

In addition to divination through the liver there were various other methods of divination practised by Babylonians and Assyrians. Prominent among them is the pouring of oil into a basin of water, or of pouring water on oil, and then observing the bubbles and rings formed by the oil. References to this method are frequently found in ritualist texts, with allusions that point to its great antiquity.[96] Besides an interesting allusion to the use of this method by a ruler of the Cassite period (c. 1700 B.C.), before undertaking an expedition to a distant land to bring back the statues of Marduk and his consort, which had been carried off by an enemy,[97] we have two elaborate texts, dating from the Hammurapi period,[98] forming a handbook for the guidance of the bârû priests, which expound a large number of signs to be observed in the mingling of oil and water, together with the interpretations thereof. From these examples we can reconstruct the system devised by the priests, which, as in the case of hepatoscopy, rested largely upon an association of ideas, but in part also upon the record of subsequent events. Divination by oil is, however, entirely overshadowed by the pre-eminence obtained by hepatoscopy, and does not appear to have formed, at least in the later periods, an integral part of the cult.

The field of divination was still further enlarged by the inclusion of all unusual happenings in the life of man, or of animals or in nature, which, in any way, aroused attention. The suspense and anxiety created by such happenings could be relieved only through a bârû priest if happily he could ascertain, by virtue of his closer relations to the gods, what the latter intended by these ominous signs. Extensive collections of all kinds of these everyday omens were made by the priests (just like the liver divinations), the aim whereof is to set forth, in a systematic manner everything of an unusual character that followed the omen. The scope is boundless, embracing as it does strange movements among animals, such as the mysterious appearance and disappearance of serpents, which impart to them a peculiar position among all ancient nations; or the actions of dogs who to this day, in the Orient, enjoy some of the privileges accorded only to sacred animals. The flight of birds was regarded as fraught with significance; swarms of locusts were a momentous warning in every sense of the word; with ravens also the Babylonians, in common with many another nation, associated forebodings, though not always of a gloomy character.

Monstrosities among men and brutes, and all manner of peculiarities among infants or the young of animals, or among those giving birth to them, form another large division in the extensive series of omens compiled by the Babylonian and Assyrian priests. The mystery of life, giving rise everywhere to certain customs observed at birth and death, would naturally fix attention on the conditions under which a new life was ushered into the world; yet many of the contingencies recorded in this division, as well as in others, are so remote and indeed so improbable as to leave on us the impression that, to some extent, at least, these collections may be purely academic exercises, devised to illustrate the application of the underlying principles of the whole system of interpretation. There can be no doubt, however, of the practical purpose also served by these collections, after making due allowance for their partially theoretical character. Their special interest for us lies in their representing a phase of divination wherein the private individual had a larger share. While the priests are in all cases the interpreters of omens and incidents, there is no reason to suppose that the consultation of them was limited to the rulers.