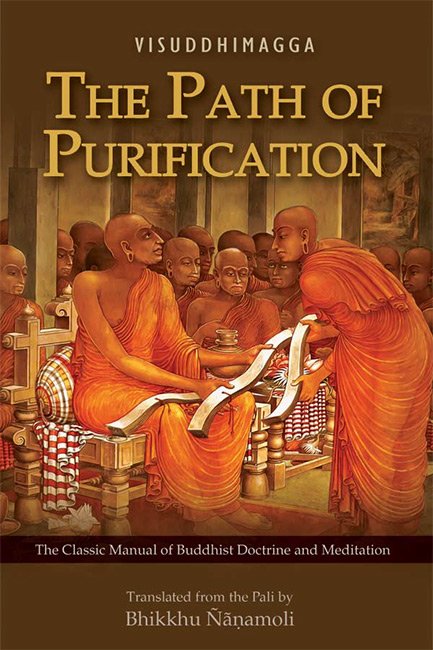

Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes Insight (1): Knowledge of Rise and Fall—II of the section Purification by Knowledge and Vision of the Way of Part 3 Understanding (Paññā) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

Insight (1): Knowledge of Rise and Fall—II

[Full title: Insight: The Eight Knowledges (1): Knowledge of Rise and Fall—II]

3. Now, the characteristics fail to become apparent when something is not given attention and so something conceals them. What is that? Firstly, the characteristic of impermanence does not become apparent because when rise and fall are not given attention, it is concealed by continuity. The characteristic of pain does not become apparent because, when continuous oppression is not given attention, it is concealed by the postures. The characteristic of not-self does not become apparent because when resolution into the various elements is not given attention, it is concealed by compactness.

4. However, when continuity is disrupted by discerning rise and fall, the characteristic of impermanence becomes apparent in its true nature.

When the postures are exposed by attention to continuous oppression, the characteristic of pain becomes apparent in its true nature. When the resolution of the compact is effected by resolution into elements, the characteristic of notself becomes apparent in its true nature.[1]

5. And here the following differences should be understood: the impermanent, and the characteristic of impermanence; the painful, and the characteristic of pain; the not-self, and the characteristic of not-self.

6. Herein, the five aggregates are impermanent. Why? Because they rise and fall and change, or because of their non-existence after having been. Rise and fall and change are the characteristic of impermanence; or mode alteration, in other words, non-existence after having been [is the characteristic of impermanence].[2]

7. Those same five aggregates are painful because of the words, “What is impermanent is painful” (S III 22). Why? Because of continuous oppression. The mode of being continuously oppressed is the characteristic of pain.

8. Those same five aggregates are not-self because of the words, “What is painful is not-self” (S III 22). Why? Because there is no exercising of power over them. The mode of insusceptibility to the exercise of power is the characteristic of notself.

9. The meditator observes all this in its true nature with the knowledge of the contemplation of rise and fall, in other words, with insight free from imperfections and steady on its course.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Cf. Peṭ 128. In the commentary to the Āyatana-Vibhaṅga we find:

“Impermanence is obvious, as when a saucer (say) falls and breaks; … pain is obvious, as when a boil (say) appears in the body; … the characteristic of not-self is not obvious; … Whether Perfect Ones arise or do not arise the characteristics of impermanence and pain are made known, but unless there is the arising of a Buddha the characteristic of not-self is not made known” (Vibh-a 49–50, abridged for clarity).

Again, in the commentary to Majjhima Nikāya Sutta 22:

“Having been, it is not, therefore it is impermanent; it is impermanent for four reasons, that is, in the sense of the state of rise and fall, of change, of temporariness, and of denying permanence. It is painful on account of the mode of oppression; it is painful for four reasons, that is, in the sense of burning, of being hard to bear, of being the basis for pain, and of opposing pleasure … It is not-self on account of the mode of insusceptibility to the exercise of power; it is not-self for four reasons, that is, in the sense of voidness, of having no owner-master, of having no Overlord, and of opposing self (M-a II 113, abridged for clarity).

Commenting on this Vism paragraph, Vism-mhṭ says:

“‘When continuity is disrupted’ means when continuity is exposed by observing the perpetual otherness of states as they go on occurring in succession. For it is not through the connectedness of states that the characteristic of impermanence becomes apparent to one who rightly observes rise and fall, but rather the characteristic becomes more thoroughly evident through their disconnectedness, as if they were iron darts.

‘When the postures are exposed’ means when the concealment of the pain that is actually inherent in the postures is exposed. For when pain arises in a posture, the next posture adopted removes the pain, as it were, concealing it. But once it is correctly known how the pain in any posture is shifted by substituting another posture for that one, then the concealment of the pain that is in them is exposed because it has become evident that formations are being incessantly overwhelmed by pain.

‘Resolution of the compact’ is effected by resolving [what appears compact] in this way, ‘The earth element is one, the water element is another’ etc., distinguishing each one; and in this way, ‘Contact is one, feeling is another’ etc., distinguishing each one.

‘When the resolution of the compact is effected’ means that what is compact as a mass and what is compact as a function or as an object has been analyzed. For when material and immaterial states have arisen mutually steadying each other, [mentality and materiality, for example,] then, owing to misinterpreting that as a unity, compactness of mass is assumed through failure to subject formations to pressure. And likewise compactness of function is assumed when, although definite differences exist in such and such states’ functions, they are taken as one. And likewise compactness of object is assumed when, although differences exist in the ways in which states that take objects make them their objects, those objects are taken as one. But when they are seen after resolving them by means of knowledge into these elements, they disintegrate like froth subjected to compression by the hand. They are mere states (dhamma) occurring due to conditions and void. In this way the characteristic of not-self becomes more evident” (Vism-mhṭ 824).

[2]:

“These modes, [that is, the three characteristics,] are not included in the aggregates because they are states without individual essence (asabhāva-dhammā);and they are not separate from the aggregates because they are unapprehendable without the aggregates. But they should be understood as appropriate conceptual differences (paññatti-visesā) that are reason for differentiation in the explaining of dangers in the five aggregates, and which are allowable by common usage in respect of the five aggregates” (Vism-mhṭ 825).