Visuddhimagga (the pah of purification)

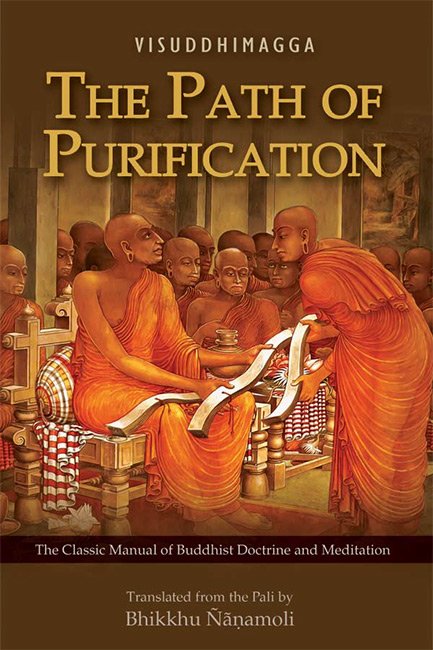

by Ñāṇamoli Bhikkhu | 1956 | 388,207 words | ISBN-10: 9552400236 | ISBN-13: 9789552400236

This page describes (1) Recollection of the Enlightened One of the section Six Recollections (Cha-anussati-niddesa) of Part 2 Concentration (Samādhi) of the English translation of the Visuddhimagga (‘the path of purification’) which represents a detailled Buddhist meditation manual, covering all the essential teachings of Buddha as taught in the Pali Tipitaka. It was compiled Buddhaghosa around the 5th Century.

(1) Recollection of the Enlightened One

2. [198] Now, a meditator with absolute confidence[1] who wants to develop firstly the recollection of the Enlightened One among these ten should go into solitary retreat in a favourable abode and recollect the special qualities of the Enlightened One, the Blessed One, as follows:

That Blessed One is such since he is accomplished, fully enlightened, endowed with [clear] vision and [virtuous] conduct, sublime, the knower of worlds, the incomparable leader of men to be tamed, the teacher of gods and men, enlightened and blessed (M I 37; A III 285).

3. Here is the way he recollects: “That Blessed One is such since he isaccomplished, he is such since he is fully enlightened, … he is such since he is blessed”—he is so for these several reasons, is what is meant.

[Accomplished]

4. Herein, what he recollects firstly is that the Blessed One is accomplished (arahanta) for the following reasons: (i) because of remoteness (āraka), and (ii) because of his enemies (ari) and (iii) the spokes (ara) having been destroyed (hata), and (iv) because of his worthiness (araha) of requisites, etc., and (v) because of absence of secret (rahābhāva) evil-doing.[2]

5. (i) He stands utterly remote and far away from all defilements because he hasexpunged all trace of defilement by means of the path—because of such remoteness (āraka) he is accomplished (arahanta).

A man remote (āraka) indeed we call

From something he has not at all;

The Saviour too that has no stain

May well the name “accomplished” (arahanta) gain.

6. (ii) And these enemies (ari), these defilements, are destroyed (hata) by the path—because the enemies are thus destroyed he is accomplished (arahanta) also.

The enemies (ari) that were deployed,

Greed and the rest, have been destroyed (hata)

By his, the Helper’s, wisdom’s sword,

So he is “accomplished” (arahanta), all accord.

7. (iii) Now, this wheel of the round of rebirths with its hub made of ignorance and of craving for becoming, with its spokes consisting of formations of merit and the rest, with its rim of ageing and death, which is joined to the chariot of

the triple becoming by piercing it with the axle made of the origins of cankers (see M I 55), has been revolving throughout time that has no beginning. All of this wheel’s spokes (ara) were destroyed (hata) by him at the Place of Enlightenment, as he stood firm with the feet of energy on the ground of virtue, wielding with the hand of faith the axe of knowledge that destroys kamma—because the spokes are thus destroyed he is accomplished (arahanta) also.

8. Or alternatively, it is the beginningless round of rebirths that is called the “wheel of the round of rebirths.” Ignorance is its hub because it is its root. Ageing-and-death is its rim because it terminates it. The remaining ten states [of the dependent origination] are its spokes because ignorance is their root and ageing-and-death their termination.

9. Herein, ignorance is unknowing about suffering and the rest. And ignorance in sensual becoming [199] is a condition for formations in sensual becoming. Ignorance in fine-material becoming is a condition for formations in fine-material becoming. Ignorance in immaterial becoming is a condition for formations in immaterial becoming.

10. Formations in sensual becoming are a condition for rebirth-linking consciousness in sensual becoming. And similarly with the rest.

11. Rebirth-linking consciousness in sensual becoming is a condition for mentality-materiality in sensual becoming. Similarly in fine-material becoming. In immaterial becoming it is a condition for mentality only.

12. Mentality-materiality in sensual becoming is a condition for the sixfold base in sensual becoming. Mentality-materiality in fine-material becoming is a condition for three bases in fine-material becoming. Mentality in immaterial becoming is a condition for one base in immaterial becoming.

13. The sixfold base in sensual becoming is a condition for six kinds of contact in sensual becoming. Three bases in fine-material becoming are conditions for three kinds of contact in fine-material becoming. The mind base alone in immaterial becoming is a condition for one kind of contact in immaterial becoming.

14. The six kinds of contact in sensual becoming are conditions for six kinds of feeling in sensual becoming. Three kinds of contact in fine-material becoming are conditions for three kinds of feeling there too. One kind of contact in immaterial becoming is a condition for one kind of feeling there too.

15. The six kinds of feeling in sensual becoming are conditions for the six groups of craving in sensual becoming. Three in the fine-material becoming are for three there too. One kind of feeling in the immaterial becoming is a condition for one group of craving in the immaterial becoming. The craving in the several kinds of becoming is a condition for the clinging there.

16. Clinging, etc., are the respective conditions for becoming and the rest. In what way? Here someone thinks, “I shall enjoy sense desires,” and with sensedesire clinging as condition he misconducts himself in body, speech, and mind. Owing to the fulfilment of his misconduct he reappears in a state of loss (deprivation). The kamma that is the cause of his reappearance there is kammaprocess becoming, the aggregates generated by the kamma are rebirth-process becoming, the generating of the aggregates is birth, their maturing is ageing, their dissolution is death.

17. Another thinks, “I shall enjoy the delights of heaven,” and in the parallel manner he conducts himself well. Owing to the fulfilment of his good conduct he reappears in a [sensual-sphere] heaven. The kamma that is the cause of his reappearance there is kamma-process becoming, and the rest as before.

18. Another thinks, “I shall enjoy the delights of the Brahmā-world,” and with sense-desire clinging as condition he develops loving-kindness, compassion, gladness, and equanimity.[3] [200] Owing to the fulfilment of the meditative development he is reborn in the Brahmā-world. The kamma that is the cause of his rebirth there is kamma-process becoming, and the rest is as before.

19. Yet another thinks, “I shall enjoy the delights of immaterial becoming,” and with the same condition he develops the attainments beginning with the base consisting of boundless space. Owing to the fulfilment of the development he is reborn in one of these states. The kamma that is the cause of his rebirth there is kamma-process becoming, the aggregates generated by the kamma are rebirthprocess becoming, the generating of the aggregates is birth, their maturing is ageing, their dissolution is death (see M II 263). The remaining kinds of clinging are construable in the same way.

20. So, “Understanding of discernment of conditions thus, ‘Ignorance is a cause, formations are causally arisen, and both these states are causally arisen,’ is knowledge of the causal relationship of states. Understanding of discernment of conditions thus, ‘In the past and in the future ignorance is a cause, formations are causally arisen, and both these states are causally arisen,’ is knowledge of the causal relationship of states” (Paṭis I 50), and all the clauses should be given in detail in this way.

21. Herein, ignorance and formations are one summarization;consciousness, mentality-materiality, the sixfold base, contact, and feeling are another; craving, clinging, and becoming are another; and birth and ageing-and-death are another. Here the first summarization is past, the two middle ones are present, and birth and ageing-and-death are future. When ignorance and formations are mentioned, thentates, became dispassionate towards them, when his greed faded away, when he was liberated, then he destroyed, quite destroyed, abolished, the spokes of this wheel of the round of rebirths of the kind just described.

22. Now, the Blessed One knew, saw, understood, and penetrated in all aspects this dependent origination with its four summarizations, its three times, its twenty aspects, and its three links. “Knowledge is in the sense of that being known,[4] and understanding is in the sense of the act of understanding that.

Hence it was said: ‘Understanding of discernment of conditions is knowledge of the causal relationship of states’” (Paṭis I 52). Thus when the Blessed One, by correctly knowing these states with knowledge of relations of states, became dispassionate towards them, when his greed faded away, when he was liberated, then he destroyed, quite destroyed, abolished, the spokes of this wheel of the round of rebirths of the kind just described.

Because the spokes are thus destroyed he is accomplished (arahanta) also.

[201] The spokes (ara) of rebirth’s wheel have been

Destroyed (hata) with wisdom’s weapon keen

By him, the Helper of the World,

And so “accomplished” (arahanta) he is called.

23. (iv) And he is worthy (arahati) of the requisites of robes, etc., and of the distinction of being accorded homage because it is he who is most worthy of offerings. For when a Perfect One has arisen, important deities and human beings pay homage to none else; for Brahmā Sahampati paid homage to the Perfect One with a jewelled garland as big as Sineru, and other deities did so according to their means, as well as human beings as King Bimbisāra [of Magadha] and the king of Kosala. And after the Blessed One had finally attained Nibbāna, King Asoka renounced wealth to the amount of ninety-six million for his sake and founded eight-four thousand monasteries throughout all Jambudīpa (India). And so, with all these, what need to speak of others? Because of worthiness of requisites he is accomplished (arahanta) also.

So he is worthy, the Helper of the World,

Of homage paid with requisites; the word

“Accomplished” (arahanta) has this meaning in the world:

Hence the Victor is worthy of that word.

24. (v) And he does not act like those fools in the world who vaunt their cleverness and yet do evil, but in secret for fear of getting a bad name. Because of absence of secret (rahābhāva) evil-doing he is accomplished (arahanta) also.

No secret evil deed may claim

An author so august; the name

“Accomplished” (arahanta) is his deservedly

By absence of such secrecy (rahābhāva).

25. So in all ways:

The Sage of remoteness unalloyed,

Vanquished defiling foes deployed,

The spokes of rebirth’s wheel destroyed,

Worthy of requisites employed,

Secret evil he does avoid:

For these five reasons he may claim

This word “accomplished” for his name.

[Full Enlightened]

26. He is fully enlightened (sammāsambuddha) because he has discovered (buddha) all things rightly (sammā) and by himself (sāmaṃ).

In fact, all things were discovered by him rightly by himself in that he discovered, of the things to be directly known, that they must be directly known (that is, learning about the four truths), of the things to be fully understood that they must be fully understood (that is, penetration of suffering), of the things to be abandoned that they must be abandoned (that is, penetration of the origin of suffering), of the things to be realized that they must be realized (that is, penetration of the cessation of suffering), and of the things to be developed that they must be developed (that is, penetration of the path). Hence it is said:

What must be directly known is directly known,

What has to be developed has been developed,

What has to be abandoned has been abandoned;

And that, brahman, is why I am enlightened (Sn 558).

27.[202] Besides, he has discovered all things rightly by himself step by step thus: The eye is the truth of suffering; the prior craving that originates it by being its root-cause is the truth of origin; the non-occurrence of both is the truth of cessation; the way that is the act of understanding cessation is the truth of the path. And so too in the case of the ear, the nose, the tongue, the body, and the mind.

28. And the following things should be construed in the same way:

the six bases beginning with visible objects;

the six groups of consciousness beginning with eye-consciousness;

the six kinds of contact beginning with eye-contact;

the six kinds of feeling beginning with the eye-contact-born;

the six kinds of perception beginning with perception of visible objects;

the six kinds of volition beginning with volition about visible objects;

the six groups of craving beginning with craving for visible objects;

the six kinds of applied thought beginning with applied thought about visible objects;

the six kinds of sustained thought beginning with sustained thought about visible objects;

the five aggregates beginning with the aggregate of matter;

the ten kasiṇas;

the ten recollections;

the ten perceptions beginning with perception of the bloated;

the thirty-two aspects [of the body] beginning with head hairs;

the twelve bases;

the eighteen elements;

the nine kinds of becoming beginning with sensual becoming;[5]

the four jhānas beginning with the first;

the four measureless states beginning with the development of loving-kindness;

the four immaterial attainments;

the factors of the dependent origination in reverse order beginning with ageing-and-death and in forward order beginning with ignorance (cf. XX.9).

29. Herein, this is the construction of a single clause [of the dependent origination]: Ageing-and-death is the truth of suffering, birth is the truth of origin, the escape from both is the truth of cessation, the way that is the act of understanding cessation is the truth of the path.

In this way he has discovered, progressively discovered, completely discovered, all states rightly and by himself step by step. Hence it was said above: “He is fully enlightened because he has discovered all things rightly and by himself” (§26).[6]

[Endowed with Clear Vision and Virtuous Conduct]

30. He is endowed with [clear] vision and [virtuous] conduct: vijjācaraṇasampanno = vijjāhi caraṇena ca sampanno (resolution of compound).

Herein, as to [clear] vision: there are three kinds of clear vision and eight kinds of clear vision. The three kinds should be understood as stated in the Bhayabherava Sutta (M I 22f.), and the eight kinds as stated in the Ambaṭṭha Sutta (D I 100). For there eight kinds of clear vision are stated, made up of the six kinds of direct-knowledge together with insight and the supernormal power of the mind-made [body].

31. [Virtuous] conduct should be understood as fifteen things, that is to say: restraint by virtue, guarding of the sense faculties, knowledge of the right amount in eating, devotion to wakefulness, the seven good states,[7] and the four jhānas of the fine-material sphere. For it is precisely by means of these fifteen things that a noble disciple conducts himself, that he goes towards the deathless. That is why it is called “[virtuous] conduct,” according as it is said, “Here, Mahānāma, a noble disciple has virtue” (M I 355), etc, the whole of which should be understood as given in the Middle Fifty [of the Majjhima Nikāya].

[203] Now, the Blessed One is endowed with these kinds of clear vision and with this conduct as well; hence he is called “endowed with [clear] vision and [virtuous] conduct.”

32. Herein, the Blessed One’s possession of clear vision consists in the fulfilment of omniscience (Paṭis I 131), while his possession of conduct consists in the fulfilment of the great compassion (Paṭis I 126). He knows through omniscience what is good and harmful for all beings, and through compassion he warns them of harm and exhorts them to do good. That is how he is possessed of clear vision and conduct, which is why his disciples have entered upon the good way instead of entering upon the bad way as the self-mortifying disciples of those who are not possessed of clear vision and conduct have done.[8]

[Sublime]

33. He is called sublime (sugata)[9] (i) because of a manner of going that is good (sobhaṇa-gamana), (ii) because of being gone to an excellent place (sundaraṃ ṭhānaṃ gatattā), (iii) because of having gone rightly (sammāgatattā), and (iv) because of enunciating rightly (sammāgadattā).

(i) A manner of going (gamana) is called “gone” (gata), and that in the Blessed One is good (sobhaṇa), purified, blameless. But what is that? It is the noble path; for by means of that manner of going he has “gone” without attachment in the direction of safety—thus he is sublime (sugata) because of a manner of going that is good.

(ii) And it is to the excellent (sundara) place that he has gone (gata), to the deathless Nibbāna—thus he is sublime (sugata) also because of having gone to an excellent place.

34. (iii) And he has rightly (sammā) gone (gata), without going back again to the defilements abandoned by each path. For this is said: “He does not again turn, return, go back, to the defilements abandoned by the stream entry path, thus he is sublime … he does not again turn, return, go back, to the defilements abandoned by the Arahant path, thus he is sublime” (old commentary?). Or alternatively, he has rightly gone from the time of [making his resolution] at the feet of Dīpaṅkara up till the Enlightenment Session, by working for the welfare and happiness of the whole world through the fulfilment of the thirty perfections and through following the right way without deviating towards either of the two extremes, that is to say, towards eternalism or annihilationism, towards indulgence in sense pleasures or self-mortification—thus he is sublime also because of having gone rightly.

35. (iv) And he enunciates[10] (gadati) rightly (sammā); he speaks only fitting speech in the fitting place—thus he is sublime also because of enunciating rightly.

Here is a sutta that confirms this: “Such speech as the Perfect One knows to be untrue and incorrect, conducive to harm, and displeasing and unwelcome to others, that he does not speak. And such speech as the Perfect One knows to be true and correct, but conducive to harm, and displeasing and unwelcome to others, that he does not speak. [204] And such speech as the Perfect One knows to be true and correct, conducive to good, but displeasing and unwelcome to others, that speech the Perfect One knows the time to expound. Such speech as the Perfect One knows to be untrue and incorrect, and conducive to harm, but pleasing and welcome to others, that he does not speak. And such speech as the Perfect One knows to be true and correct, but conducive to harm, though pleasing and welcome to others, that he does not speak. And such speech as the Perfect One knows to be true and correct, conducive to good, and pleasing and welcome to others, that speech the Perfect One knows the time to expound” (M I 395)—thus he is sublime also because of enunciating rightly.

[Knower of Worlds]

36. He is the knower of worlds because he has known the world in all ways. For the Blessed One has experienced, known and penetrated the world in all ways to its individual essence, its arising, its cessation, and the means to its cessation, according as it is said: “Friend, that there is a world’s end where one neither is born nor ages nor dies nor passes away nor reappears, which is to be known or seen or reached by travel—that I do not say. Yet I do not say that there is ending of suffering without reaching the world’s end. Rather, it is in this fathom-long carcass with its perceptions and its consciousness that I make known the world, the arising of the world, the cessation of the world, and the way leading to the cessation of the world.

“Tis utterly impossible

To reach by travel the world’s end;

But there is no escape from pain

Until the world’s end has been reached.

It is a sage, a knower of the worlds,

Who gets to the world’s end, and it is he

Whose life divine is lived out to its term;

He is at peace who the world’s end has known

And hopes for neither this world nor the next” (S I 62).

37. Moreover, there are three worlds: the world of formations, the world of beings, and the world of location. Herein, in the passage, “One world: all beings subsist by nutriment” (Paṭis I 122), [205] the world of formations is to be understood. In the passage, “‘The world is eternal’ or ‘The world is not eternal’” (M I 426) it is the world of beings. In the passage:

“As far as moon and sun do circulate

Shining[11] and lighting up the [four] directions,

Over a thousand times as great a world

Your power holds unquestionable sway” (M I 328)—

it is the world of location. The Blessed One has known that in all ways too.

38. Likewise, because of the words: “One world: all beings subsist by nutriment. Two worlds: mentality and materiality. Three worlds: three kinds of feeling. Four worlds: four kinds of nutriment. Five worlds: five aggregates as objects of clinging. Six worlds: six internal bases. Seven worlds: seven stations of consciousness. Eight worlds: eight worldly states. Nine worlds: nine abodes of beings. Ten worlds: ten bases. Twelve worlds: twelve bases. Eighteen worlds: eighteen elements” (Paṭis I 122),[12] this world of formations was known to him in all ways.

39. But he knows all beings’ habits, knows their inherent tendencies, knows their temperaments, knows their bents, knows them as with little dust on their eyes and with much dust on their eyes, with keen faculties and with dull faculties, with good behaviour and with bad behaviour, easy to teach and hard to teach, capable and incapable [of achievement] (cf. Paṭis I 121), therefore this world of beings was known to him in all ways.

40. And as the world of beings so also the world of location. For accordingly this [world measures as follows]:

One world-sphere[13] is twelve hundred thousand leagues and thirty-four hundred and fifty leagues (1,203,450) in breadth and width. In circumference, however:

[The measure of it] all around

Is six and thirty hundred thousand

And then ten thousand in addition,

Four hundred too less half a hundred (3,610,350).

41. Herein:

Two times a hundred thousand leagues

And then four nahutas as well (240,000):

This earth, this “Bearer of All Wealth,”

Has that much thickness, as they tell.

And its support:

Four times a hundred thousand leagues

And then eight nahutas as well (480,000):

The water resting on the air

Has that much thickness, as they tell.

And the support of that: [206]

Nine times a hundred thousand goes

The air out in the firmament

And sixty thousand more besides (960,000)

So this much is the world’s extent.

42. Such is its extent. And these features are to be found in it:

Sineru, tallest of all mountains, plunges down into the sea

Full four and eighty thousand leagues, and towers up in like degree

Seven concentric mountain rings surround Sineru in suchwise

That each of them in depth and height is half its predecessor’s size:

Vast ranges called Yugandhara, Īsadhara, Karavīka,

Sudassana, Nemindhara, Vinataka, Assakaṇṇa.

Heavenly [breezes fan] their cliffs agleam with gems, and here reside

The Four Kings of the Cardinal Points, and other gods and sprites beside.[14]

Himālaya’s lofty mountain mass rises in height five hundred leagues

And in its width and in its breadth it covers quite three thousand leagues,

And then it is bedecked besides with four and eighty thousand peaks.[15]

The Jambu Tree called Nāga lends the name, by its magnificence,

To Jambudīpa’s land; its trunk, thrice five leagues in circumference,

Soars fifty leagues, and bears all round branches of equal amplitude,

So that a hundred leagues define diameter and altitude.

43.

The World-sphere Mountains’ line of summits plunges down into the sea

Just two and eighty thousand leagues, and towers up in like degree,

Enringing one world-element all round in its entirety.

And the size of the Jambu (Rose-apple) Tree is the same as that of the Citrapāṭaliya Tree of the Asura demons, the Simbali Tree of the Garuḷa demons, the Kadamba Tree in [the western continent of] Aparagoyana, the Kappa Tree [in the northern continent] of the Uttarakurus, the Sirīsa Tree in [the eastern continent of] Pubbavideha, and the Pāricchattaka Tree [in the heaven] of the Deities of the Thirty-three (Tāvatiṃsa).[16] Hence the Ancients said:

The Pāṭali, Simbali, and Jambu, the deities’ Pāricchattaka, The Kadamba, the Kappa Tree and the Sirīsa as the seventh.

44. [207] Herein, the moon’s disk is forty-nine leagues [across] and the sun’s disk is fifty leagues. The realm of Tāvatiṃsa (the Thirty-three Gods) is ten thousand leagues. Likewise the realm of the Asura demons, the great Avīci (unremitting) Hell, and Jambudīpa (India). Aparagoyāna is seven thousand leagues. Likewise Pubbavideha. Uttarakurū is eight thousand leagues. And herein, each great continent is surrounded by five hundred small islands. And the whole of that constitutes a single world-sphere, a single world-element. Between [this and the adjacent world-spheres] are the Lokantarika (worldinterspace) hells.[17] So the world-spheres are infinite in number, the worldelements are infinite, and the Blessed One has experienced, known and penetrated them with the infinite knowledge of the Enlightened Ones.

45. Therefore this world of location was known to him in all ways too. So he is “knower of worlds” because he has seen the world in all ways.

[Incomparable Leader of Men to be Tamed]

46. In the absence of anyone more distinguished for special qualities than himself, there is no one to compare with him, thus he is incomparable. For in this way he surpasses the whole world in the special quality of virtue, and also in the special qualities of concentration, understanding, deliverance, and knowledge and vision of deliverance. In the special quality of virtue he is without equal, he is the equal only of those [other Enlightened Ones] without equal, he is without like, without double, without counterpart; … in the special quality of knowledge and vision of deliverance he is … without counterpart, according as it is said: “I do not see in the world with its deities, its Māras and its Brahmās, in this generation with its ascetics and brahmans, with its princes and men,[18] anyone more perfect in virtue than myself” (S I 139), with the rest in detail, and likewise in the Aggappasāda Sutta (A II 34; It 87), and so on, and in the stanzas beginning, “I have no teacher and my like does not exist in all the world” (M I 171), all of which should be taken in detail.

47. He guides (sāreti) men to be tamed (purisa-damme), thus he is leader of men to be tamed (purisadammasārathī); he tames, he disciplines, is what is meant. Herein, animal males (purisā) and human males, and non-human males that are not tamed but fit to be tamed (dametuṃ yuttā) are “men to be tamed” (purisadammā). For the animal males, namely, the royal nāga (serpent) Apalāla, Cūḷodara, Mahodara, Aggisikha, Dhūmasikha, the royal nāga Āravāḷa, the elephant Dhanapālaka, and so on, were tamed by the Blessed One, freed from the poison [of defilement] and established in the refuges and the precepts of virtue; and also the human males, namely, Saccaka the Nigaṇṭhas’ (Jains’) son, the brahman student Ambaṭṭha, [208] Pokkharasāti, Soṇadaṇḍa, Kūṭadanta, and so on; and also the non-human males, namely, the spirits Āḷavaka, Sūciloma and Kharaloma, Sakka Ruler of Gods, etc.,[19] were tamed and disciplined by various disciplinary means. And the following sutta should be given in full here: “I discipline men to be tamed sometimes gently, Kesi, and I discipline them sometimes roughly, and I discipline them sometimes gently and roughly” (A II 112).

48. Then the Blessed One moreover further tames those already tamed, doing so by announcing the first jhāna, etc., respectively to those whose virtue is purified, etc., and also the way to the higher path to stream enterers, and so on.

Or alternatively, the words incomparable leader of men to be tamed can be taken together as one clause. For the Blessed One so guides men to be tamed that in a single session they may go in the eight directions [by the eight liberations] without hesitation. Thus he is called the incomparable leader of men to be tamed. And the following sutta passage should be given in full here: “Guided by the elephant-tamer, bhikkhus, the elephant to be tamed goes in one direction …” (M III 222).

[Teacher of Gods and Men]

49. He teaches (anusāsati) by means of the here and now, of the life to come, and of the ultimate goal, according as befits the case, thus he is the Teacher (satthar). And furthermore this meaning should be understood according to the Niddesa thus: “‘Teacher (satthar)’: the Blessed One is a caravan leader (satthar) since he brings home caravans (sattha). Just as one who brings a caravan home gets caravans across a wilderness, gets them across a robber-infested wilderness, gets them across a wild-beast-infested wilderness, gets them across a foodless wilderness, gets them across a waterless wilderness, gets them right across, gets them quite across, gets them properly across, gets them to reach a land of safety, so too the Blessed One is a caravan leader, one who brings home the caravans, he gets them across a wilderness, gets them across the wilderness of birth” (Nidd I 446).

50. Of gods and men: devamanussānaṃ = devānañ ca manussānañ ca (resolution of compound). This is said in order to denote those who are the best and also to denote those persons capable of progress. For the Blessed One as a teacher bestowed his teaching upon animals as well. For when animals can, through listening to the Blessed One’s Dhamma, acquire the benefit of a [suitable rebirth as] support [for progress], and with the benefit of that same support they come, in their second or third rebirth, to partake of the path and its fruition.

51. Maṇḍūka, the deity’s son, and others illustrate this. While the Blessed One was teaching the Dhamma to the inhabitants of the city of Campā on the banks of the Gaggarā Lake, it seems, a frog (maṇḍūka) apprehended a sign in the Blessed One’s voice. [209] A cowherd who was standing leaning on a stick put his stick on the frog’s head and crushed it. He died and was straight away reborn in a gilded, divine palace, twelve leagues broad in the realm of the Thirtythree (Tāvatiṃsa). He found himself there, as if waking up from sleep, amidst a host of celestial nymphs, and he exclaimed, “So I have actually been reborn here. What deed did I do?” When he sought for the reason, he found it was none other than his apprehension of the sign in the Blessed One’s voice. He went with his divine palace at once to the Blessed One and paid homage at his feet. Though the Blessed One knew about it, he asked him:

“Who now pays homage at my feet,

Shining with glory of success,

Illuminating all around

With beauty so outstanding?”“In my last life I was a frog,

The waters of a pond my home;

A cowherd’s crook ended my life

While listening to your Dhamma” (Vv 49).

The Blessed One taught him the Dhamma. Eighty-four thousand creatures gained penetration to the Dhamma. As soon as the deity’s son became established in the fruition of stream-entry he smiled and then vanished.

[Enlightened]

52. He is enlightened (buddha) with the knowledge that belongs to the fruit of liberation, since everything that can be known has been discovered (buddha) by him.

Or alternatively, he discovered (bujjhi) the four truths by himself and awakened (bodhesi) others to them, thus and for other such reasons he is enlightened (buddha). And in order to explain this meaning the whole passage in the Niddesa beginning thus: “He is the discoverer (bujjhitar) of the truths, thus he is enlightened (buddha). He is the awakened (bodhetar) of the generation, thus he is enlightened (buddha)” (Nidd I 457), or the same passage from the Paṭisambhidā (Paṭis I 174), should be quoted in detail.

[Blessed]

53. Blessed (bhagavant) is a term signifying the respect and veneration accorded to him as the highest of all beings and distinguished by his special qualities.[20] Hence the Ancients said:

“Blessed” is the best of words,

“Blessed” is the finest word;

Deserving awe and veneration, Blessed is the name therefore.

54. Or alternatively, names are of four kinds: denoting a period of life, describing a particular mark, signifying a particular acquirement, and fortuitously arisen,[21] which last in the current usage of the world is called “capricious.” Herein, [210] names denoting a period of life are those such as “yearling calf” (vaccha), “steer to be trained” (damma), “yoke ox” (balivaddha), and the like. Names describing a particular mark are those such as “staff-bearer” (daṇḍin), “umbrella-bearer” (chattin), “topknot-wearer” (sikhin), “hand possessor” (karin—elephant), and the like. Names signifying a particular acquirement are those such as “possessor of the threefold clear vision” (tevijja), “possessor of the six direct-knowledges” (chaḷabhiñña), and the like. Such names are Sirivaḍḍhaka (“Augmenter of Lustre”), Dhanavaḍḍhaka (“Augmenter of Wealth”), etc., are fortuitously arisen names; they have no reference to the word-meanings.

55. This name, Blessed, is one signifying a particular acquirement; it is not made by Mahā-Māyā, or by King Suddhodana, or by the eighty thousand kinsmen, or by distinguished deities like Sakka, Santusita, and others. And this is said by the General of the Law:[22] “‘Blessed’: this is not a name made by a mother … This [name] ‘Buddha,’ which signifies final liberation, is a realistic description of Buddhas (Enlightened Ones), the Blessed Ones, together with their obtainment of omniscient knowledge at the root of an Enlightenment [Tree]” (Paṭis I 174; Nidd I 143).

56. Now, in order to explain also the special qualities signified by this name they cite the following stanza:

Bhagī bhajī bhāgī vibhattavā iti

Akāsi bhaggan ti garū ti bhāgyavā

Bahūhi ñāyehi subhāvitattano

Bhavantago so bhagavā ti vuccati.The reverend one (garu) has blessings (bhagī), is a frequenter (bhajī), a partaker (bhāgī), a possessor of what has been analyzed (vibhattavā);

He has caused abolishing (bhagga), he is fortunate (bhāgyavā),

He has fully developed himself (subhāvitattano) in many ways;

He has gone to the end of becoming (bhavantago);thus is called “Blessed” (bhagavā).

The meaning of these words should be understood according to the method of explanation given in the Niddesa (Nidd I 142).[23]

57. But there is this other way:

Bhāgyavā bhaggavā yutto bhagehi ca vibhattavā.

Bhattavā vanta-gamano bhavesu: bhagavā tato.He is fortunate (bhāgyavā), possessed of abolishment (bhaggavā), associated with blessings (yutto bhagehi), and a possessor of what has been analyzed (vibhattavā).

He has frequented (bhattavā), and he has rejected going in the kinds of becoming (VAnta-GAmano BHAvesu), thus he is Blessed (Bhagavā).

58. Herein, by using the characteristic of language beginning with “vowel augmentation of syllable, elision of syllable” (see Kāśika VI.3.109), or by using the characteristic of insertion beginning with [the example of] pisodara, etc. (see Pāṇini, Gaṇapāṭha 6, 3, 109), it may be known that he [can also] be called “blessed” (bhagavā) when he can be called “fortunate” (bhāgyavā) owing to the fortunateness (bhāgya) to have reached the further shore [of the ocean of perfection] of giving, virtue, etc., which produce mundane and supramundane bliss (See Khp-a 108.).

59. [Similarly], he [can also] be called “blessed” (bhagavā) when he can be called “possessed of abolishment” (bhaggavā) owing to the following menaces having been abolished; for he has abolished (abhañji) all the hundred thousand kinds of trouble, anxiety and defilement classed as greed, as hate, as delusion, and as misdirected attention; as consciencelessness and shamelessness, as anger and enmity, as contempt and domineering, as envy and avarice, as deceit and fraud, as obduracy and presumption, as pride and haughtiness, as vanity and negligence, as craving and ignorance; as the three roots of the unprofitable, kinds of misconduct, defilement, stains, [211] fictitious perceptions, applied thoughts, and diversifications; as the four perversenesses, cankers, ties, floods, bonds, bad ways, cravings, and clingings; as the five wildernesses in the heart, shackles in the heart, hindrances, and kinds of delight; as the six roots of discord, and groups of craving; as the seven inherent tendencies; as the eight wrongnesses; as the nine things rooted in craving; as the ten courses of unprofitable action; as the sixty-two kinds of [false] view; as the hundred and eight ways of behaviour of craving[24]—or in brief, the five Māras, that is to say, the Māras of defilement, of the aggregates, and of kamma-formations, Māra as a deity, and Māra as death.

And in this context it is said:

He has abolished (bhagga) greed and hate,

Delusion too, he is canker-free;

Abolished every evil state,

“Blessed” his name may rightly be.

60. And by his fortunateness (bhāgyavatā) is indicated the excellence of his material body which bears a hundred characteristics of merit;and by his having abolished defects (bhaggadosatā) is indicated the excellence of his Dhamma body. Likewise, [by his fortunateness is indicated] the esteem of worldly [people; and by his having abolished defects, the esteem of] those who resemble him. [And by his fortunateness it is indicated] that he is fit to be relied on[25] by laymen; and [by his having abolished defects that he is fit to be relied on by] those gone forth into homelessness; and when both have relied on him, they acquire relief from bodily and mental pain as well as help with both material and Dhamma gifts, and they are rendered capable of finding both mundane and supramundane bliss.

61. He is also called “blessed” (bhagavā) since he is “associated with blessings” (bhagehi yuttattā) such as those of the following kind, in the sense that he “has those blessings” (bhagā assa santi). Now, in the world the word “blessing” is used for six things, namely, lordship, Dhamma, fame, glory, wish, and endeavour. He has supreme lordship over his own mind, either of the kind reckoned as mundane and consisting in “minuteness, lightness,” etc.,[26] or that complete in all aspects, and likewise the supramundane Dhamma. And he has exceedingly pure fame, spread through the three worlds, acquired though the special quality of veracity. And he has glory of all limbs, perfect in every aspect, which is capable of comforting the eyes of people eager to see his material body. And he has his wish, in other words, the production of what is wanted, since whatever is wanted and needed by him as beneficial to himself or others is then and there produced for him. And he has the endeavour, in other words, the right effort, which is the reason why the whole world venerates him.

62. [He can also] be called “blessed” (bhagavā) when he can be called “a possessor of what has been analyzed” (vibhattavā) owing to his having analyzed [and clarified] all states into the [three] classes beginning with the profitable; or profitable, etc., states into such classes as aggregates, bases, elements, truths, faculties, dependent origination, etc.;[212] or the noble truth of suffering into the senses of oppressing, being formed, burning, and changing; and that of origin into the senses of accumulating, source, bond, and impediment; and that of cessation into the senses of escape, seclusion, being unformed, and deathless; and that of the path into the senses of outlet, cause, seeing, and predominance. Having analyzed, having revealed, having shown them, is what is meant.

63. He [can also] be called “blessed” (bhagavā) when he can be called one who “has frequented” (bhattavā) owing to his having frequented (bhaji), cultivated, repeatedly practiced, such mundane and supramundane higher-than-human states as the heavenly, the divine, and the noble abidings,[27] as bodily, mental, and existential seclusion, as the void, the desireless, and the signless liberations, and others as well.

64. He [can also] be called “blessed” (bhagavā) when he can be called one who “has rejected going in the kinds of becoming” (vantagamano bhavesu) because in the three kinds of becoming (bhava), the going (gamana), in other words, craving, has been rejected (vanta) by him. And the syllables bha from the word bhava, and ga from the word gamana, and va from the word vanta with the letter a lengthened, make the word bhagavā, just as is done in the world [of the grammarians outside the Dispensation] with the word mekhalā (waist-girdle) since “garland for the private parts” (MEhanassa KHAssa māLĀ) can be said.

65. As long as [the meditator] recollects the special qualities of the Buddha in this way, “For this and this reason the Blessed One is accomplished, … for this and this reason he is blessed,” then: “On that occasion his mind is not obsessed by greed, or obsessed by hate, or obsessed by delusion; his mind has rectitude on that occasion, being inspired by the Perfect One” (A III 285).[28]

66. So when he has thus suppressed the hindrances by preventing obsession by greed, etc., and his mind faces the meditation subject with rectitude, then his applied thought and sustained thought occur with a tendency toward the Enlightened One’s special qualities. As he continues to exercise applied thought and sustained thought upon the Enlightened One’s special qualities, happiness arises in him. With his mind happy, with happiness as a proximate cause, his bodily and mental disturbances are tranquilized by tranquillity. When the disturbances have been tranquilized, bodily and mental bliss arise in him. When he is blissful, his mind, with the Enlightened One’s special qualities for its object, becomes concentrated, and so the jhāna factors eventually arise in a single moment. But owing to the profundity of the Enlightened One’s special qualities, or else owing to his being occupied in recollecting special qualities of many sorts, the jhāna is only access and does not reach absorption. And that access jhāna itself is known as “recollection of the Buddha” too, because it arises with the recollection of the Enlightened One’s special qualities as the means.

67. When a bhikkhu is devoted to this recollection of the Buddha, he is respectful and deferential towards the Master. He attains fullness of faith, mindfulness, understanding and merit. He has much happiness and gladness. He conquers fear and dread. [213] He is able to endure pain. He comes to feel as if he were living in the Master’s presence. And his body, when the recollection of the Buddha’s special qualities dwells in it, becomes as worthy of veneration as a shrine room. His mind tends toward the plane of the Buddhas. When he encounters an opportunity for transgression, he has awareness of conscience and shame as vivid as though he were face to face with the Master. And if he penetrates no higher, he is at least headed for a happy destiny.

Now, when a man is truly wise,

His constant task will surely be

This recollection of the Buddha

Blessed with such mighty potency.

This, firstly, is the section dealing with the recollection of the Enlightened One in the detailed explanation.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

“‘Absolute confidence’ is the confidence afforded by the noble path. Development of the recollection comes to success in him who has that, not in any other” (Vism-mhṭ 181). “Absolute confidence” is a constituent of the first three “factors of streamentry” (see S V 196).

[3]:

“Because of the words, ‘Also all dhammas of the three planes are sense desires (kāma) in the sense of being desirable (kamanīya) (Cf. Nidd I 1: sabbepi kāmāvacarā dhammā, sabbepi rūpāvacarā dhammā, sabbepi arūpāvacarā dhammā … kāmanīyaṭṭhena … kāmā), greed for becoming is sense-desire clinging’ (Vism-mhṭ 184). See XII.72. For the “way to the Brahmā-world” see M II 194–96; 207f.

[5]:

See XVII.253f. The word bhava is rendered here both by “existence” and by “becoming.” The former, while less awkward to the ear, is inaccurate if it is allowed a flavour of staticness. “Becoming” will be more frequently used as this work proceeds. Loosely the two senses tend to merge. But technically, “existence” should perhaps be used only for atthitā, which signifies the momentary existence of a dhamma “possessed of the three instants of arising, presence, and dissolution.” “Becoming” then signifies the continuous flow or flux of such triple-instant moments; and it occurs in three main modes: sensual, fine-material, and immaterial. For remarks on the words “being” and “essence” see VIII n. 68.

[6]:

“Is not unobstructed knowledge (anāvaraṇa-ñāṇa) different from omniscient knowledge (sabbaññuta-ñāṇa)? Otherwise the words “Six kinds of knowledge unshared [by disciples]” (Paṭis I 3) would be contradicted? [Note: The six kinds are: knowledge of what faculties prevail in beings, knowledge of the inclinations and tendencies of beings, knowledge of the Twin Marvel, knowledge of the attainment of the great compassion, omniscient knowledge, and unobstructed knowledge (see Paṭis I 133)].—There is no contradiction, because two ways in which a single kind of knowledge’s objective field occurs are described for the purpose of showing by means of this difference how it is not shared by others.

It is only one kind of knowledge; but it is called omniscient knowledge because its objective field consists of formed, unformed, and conventional (sammuti) [i.e. conceptual] dhammas without remainder, and it is called unobstructed knowledge because of its unrestricted access to the objective field, because of absence of obstruction. And it is said accordingly in the Paṭisambhidā: “It knows all the formed and the unformed without remainder, thus it is omniscient knowledge. It has no obstruction therein, thus it is unobstructed knowledge” (Paṭis I 131), and so on. So they are not different kinds of knowledge. And there must be no reservation, otherwise it would follow that omniscient and unobstructed knowledge had obstructions and did not make all dhammas its object. There is not in fact a minimal obstruction to the Blessed One’s knowledge: and if his unobstructed knowledge did not have all dhammas as its object, there would be presence of obstruction where it did not occur, and so it would not be unobstructed.

“Or alternatively, even if we suppose that they are different, still it is omniscient knowledge itself that is intended as ‘unhindered’ since it is that which occurs unhindered universally. And it is by his attainment of that that the Blessed One is known as Omniscient, All-seer, Fully Enlightened, not because of awareness (avabodha) of every dhamma at once, simultaneously (see M II 127). And it is said accordingly in the Paṭisambhidā: ‘This is a name derived from the final liberation of the Enlightened Ones, the Blessed Ones, together with the acquisition of omniscient knowledge at the root of the Enlightenment Tree; this name “Buddha” is a designation based on realization’ (Paṭis I 174). For the ability in the Blessed One’s continuity to penetrate all dhammas without exception was due to his having completely attained to knowledge capable of becoming aware of all dhammas.

“Here it may be asked: But how then? When this knowledge occurs, does it do so with respect to every field simultaneously, or successively? For firstly, if it occurs simultaneously with respect to every objective field, then with the simultaneous appearance of formed dhammas classed as past, future and present, internal and external, etc., and of unformed and conventional (conceptual) dhammas, there would be no awareness of contrast (paṭibhāga), as happens in one who looks at a painted canvas from a distance. That being so, it follows that all dhammas become the objective field of the Blessed One’s knowledge in an undifferentiated form (anirūpita-rūpana), as they do through the aspect of not-self to those who are exercising insight thus’All dhammas are not-self’ (Dhp 279; Th 678; M I 230; II 64; S III 132; A I 286; IV 14; Paṭis II 48, 62; Vin I 86. Cf. also A III 444; IV 88, 338; Sn 1076). And those do not escape this difficulty who say that the Enlightened One’s knowledge occurs with the characteristic of presence of all knowable dhammas as its objective field, devoid of discriminative thinking (vikappa-rahita), and universal in time (sabba-kāla) and that is why they are called’All-seeing’ and why it is said,’The Nāga is concentrated walking and he is concentrated standing’ (?).

They do not escape the difficulty since the Blessed One’s knowledge would then have only a partial objective field, because, by having the characteristic of presence as its object, past, future and conventional dhammas, which lack that characteristic, would be absent. So it is wrong to say that it occurs simultaneously with respect to every objective field. Then secondly, if we say that it occurs successively with respect to every objective field, that is wrong too. For when the knowable, classed in the many different ways according to birth, place, individual essence, etc., and direction, place, time, etc., is apprehended successively, then penetration without remainder is not effected since the knowable is infinite. And those are wrong too who say that the Blessed One is All-seeing owing to his doing his defining by taking one part of the knowable as that actually experienced (paccakkha) and deciding that the rest is the same because of the unequivocalness of its meaning, and that such knowledge is not inferential (anumānika) since it is free from doubt, because it is what is doubtfully discovered that is meant by inferential knowledge in the world. And they are wrong because there is no such defining by taking one part of the knowable as that actually experienced and deciding that the rest is the same because of the unequivocalness of its meaning, without making all of it actually experienced. For then that ‘rest’ is not actually experienced; and if it were actually experienced, it would no longer be ‘the rest.’

“All that is no argument.—Why not?—Because this is not a field for ratiocination; for the Blessed One has said this: ‘The objective field of Enlightened Ones is unthinkable, it cannot be thought out; anyone who tried to think it out would reap madness and frustration’ (A II 80). The agreed explanation here is this: Whatever the Blessed One wants to know—either entirely or partially—there his knowledge occurs as actual experience because it does so without hindrance. And it has constant concentration because of the absence of distraction. And it cannot occur in association with wishing of a kind that is due to absence from the objective field of something that he wants to know. There can be no exception to this because of the words, ‘All dhammas are available to the adverting of the Enlightened One, the Blessed One, are available at his wish, are available to his attention, are available to his thought’ (Paṭis II 195). And the Blessed One’s knowledge that has the past and future as its objective field is entirely actual experience since it is devoid of assumption based on inference, tradition or conjecture.

“And yet, even in that case, suppose he wanted to know the whole in its entirety, then would his knowledge not occur without differentiation in the whole objective field simultaneously? And so there would still be no getting out of that difficulty? “That is not so, because of its purifiedness. Because the Enlightened One’s objective field is purified and it is unthinkable. Otherwise there would be no unthinkableness in the knowledge of the Enlightened One, the Blessed One, if it occurred in the same way as that of ordinary people. So, although it occurs with all dhammas as its object, it nevertheless does so making those dhammas quite clearly defined, as though it had a single dhamma as its object. This is what is unthinkable here.”

There is as much knowledge as there is knowable, there is as much knowable as there is knowledge; the knowledge is limited by the knowable, the knowable is limited by the knowledge’ (Paṭis II l95). So he is Fully Enlightened because he has rightly and by himself discovered all dhammas together and separately, simultaneously and successively, according to his wish’ (Vism-mhṭ 190–91).

[7]:

[8]:

“Here the Master’s possession of vision shows the greatness of understanding, and his possession of conduct the greatness of his compassion. It was through understanding that the Blessed One reached the kingdom of the Dhamma, and through compassion that he became the bestower of the Dhamma. It was through understanding that he felt revulsion for the round of rebirths, and through compassion that he bore it. It was through understanding that he fully understood others’ suffering, and through compassion that he undertook to counteract it. It was through understanding that he was brought face to face with Nibbāna, and through compassion that he attained it. It was through understanding that he himself crossed over, and through compassion that he brought others across. It was through understanding that he perfected the Enlightened One’s state, and through compassion that he perfected the Enlightened One’s task.

“Or it was through compassion that he faced the round of rebirths as a Bodhisatta, and through understanding that he took no delight in it. Likewise it was through compassion that he practiced non-cruelty to others, and through understanding that he was himself fearless of others. It was through compassion that he protected others to protect himself, and through understanding that he protected himself to protect others. Likewise it was through compassion that he did not torment others, and through understanding that he did not torment himself; so of the four types of persons beginning with the one who practices for his own welfare (A II 96) he perfected the fourth and best type. Likewise it was through compassion that he became the world’s helper, and through understanding that he became his own helper. It was through compassion that he had humility [as a Bodhisatta], and through understanding that he had dignity [as a Buddha]. Likewise it was through compassion that he helped all beings as a father while owing to the understanding associated with it his mind remained detached from them all, and it was through understanding that his mind remained detached from all dhammas while owing to the compassion associated with it that he was helpful to all beings. For just as the Blessed One’s compassion was devoid of sentimental affection or sorrow, so his understanding was free from the thoughts of ‘I’ and ‘mine’” (Vism-mhṭ 192–93).

[9]:

The following renderings have been adopted for the most widely-used epithets for the Buddha. Tathāgata, (Perfect One—for definitions see M-a I 45f.) Bhagavant (Blessed One), Sugata (Sublime One). These renderings do not pretend to literalness. Attempts to be literal here are apt to produce a bizarre or quaint effect, and for that very reason fail to render what is in the Pali.

[12]:

To take what is not self-evident in this paragraph, three kinds of feeling are pleasant, painful and neither-painful-nor-pleasant (see MN 59). Four kinds of nutriment are physical nutriment, contact, mental volition, and consciousness (see M I 48, and M-a I 207f.). The seven stations of consciousness are: (1) sense sphere, (2) Brahmā’s Retinue, (3) Ābhassara (Brahmā-world) Deities, (4) Subhakiṇṇa (Brahmā-world) Deities, (5) base consisting of boundless space, (6) base consisting of boundless consciousness, (7) base consisting of nothingness (see D III 253). The eight worldly states are gain, fame, praise, pleasure, and their opposites (see D III 260). The nine abodes of beings: (1–4) as in stations of consciousness, (5) unconscious beings, (6–9) the four immaterial states (see D III 263). The ten bases are eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, visible object, sound, odour, flavour, tangible object.

[13]:

Cakkavāḷa (world-sphere or universe) is a term for the concept of a single complete universe as one of an infinite number of such universes. This concept of the cosmos, in its general form, is not peculiar to Buddhism, but appears to have been the already generally accepted one. The term loka-dhātu (world-element), in its most restricted sense, is one world-sphere, but it can be extended to mean any number, for example, the set of world-spheres dominated by a particular Brahmā (see MN 120).

As thus conceived, a circle of “world-sphere mountains” “like the rim of a wheel” (cakka—Vism-mhṭ 198) encloses the ocean. In the centre of the ocean stands Mount Sineru (or Meru), surrounded by seven concentric rings of mountains separated by rings of sea. In the ocean between the outermost of these seven rings and the enclosing “world-sphere mountain” ring are the “four continents.”

“Over forty-two thousand leagues away” (Dhs-a 313) the moon and the sun circulate above them inside the world-sphere mountain ring, and night is the effect of the sun’s going behind Sineru. The orbits of the moon and sun are in the sense-sphere heaven of the Four Kings (Catumahārājā), the lowest heaven, which is a layer extending from the world-sphere mountains to the slopes of Sineru. The stars are on both sides of them (Dhs-a 318). Above that come the successive layers of the other five sensesphere heavens—the four highest not touching the earth—and above them the fine-material Brahmā-worlds, the higher of which extend over more than one worldsphere (see A V 59). The world-sphere rests on water, which rests on air, which rests on space. World-spheres “lie adjacent to each other in contact like bowls, leaving a triangular unlit space between each three” (Vism-mhṭ 199), called a “world-interspace” (see too M-a IV 178). Their numbers extend thus in all four directions to infinity on the supporting water’s surface.

The southern continent of Jambudīpa is the known inhabited world (but see e.g. DN 26). Various hells (see e.g. MN 130; A V 173;Vin III 107) are below the earth’s surface. The lowest sensual-sphere heaven is that of the Deities of the Four Kings (Cātumahārājika). The four are Dhataraṭṭha Gandhabba-rāja (King of the East), Virūḷha Kumbhaṇḍa-rāja (King of the South), Virūpaka Nāga-rāja (King of the West), and Kuvera or Vessavaṇa Yakkha-rāja (King of the North—see DN 32). Here the moon and sun circulate. The deities of this heaven are often at war with the Asura demons (see e.g. D II 285) for possession of the lower slopes of Sineru. The next higher is Tāvatiṃsa (the Heaven of the Thirty-three), governed by Sakka, Ruler of Gods (sakkadevinda). Above this is the heaven of the Yāma Deities (Deities who have Gone to Bliss) ruled by King Suyāma (not to be confused with Yama King of the Underworld—see M III 179). Higher still come the Deities of the Tusita (Contented) Heaven with King Santusita. The fifth of these heavens is that of the Nimmānarati Deities (Deities who Delight in Creating) ruled by King Sunimmita. The last and highest of the sensualsphere heavens is the Paranimmitavasavatti Heaven (Deities who Wield Power over Others’ Creations). Their king is Vasavatti (see A I 227; for details see Vibh-a 519f.). Māra (Death) lives in a remote part of this heaven with his hosts, like a rebel with a band of brigands (M-a I 33f.). For destruction and renewal of all this at the end of the aeon, see Ch. XIII.

[14]:

“Sineru is not only 84,000 leagues in height but measures the same in width and breadth. For this is said: ‘Bhikkhus, Sineru, king of mountains, is eighty-four thousand leagues in width and it is eighty-four thousand leagues in breadth’ (A IV 100). Each of the seven surrounding mountains is half as high as that last mentioned, that is, Yugandhara is half as high as Sineru, and so on. The great ocean gradually slopes from the foot of the world-sphere mountains down as far as the foot of Sineru, where it measures in depth as much as Sineru’s height. And Yugandhara, which is half that height, rests on the earth as Īsadhara and the rest do; for it is said: ‘Bhikkhus, the great ocean gradually slopes, gradually tends, gradually inclines’ (Ud 53). Between Sineru and Yugandhara and so on, the oceans are called ‘bottomless’ (sīdanta). Their widths correspond respectively to the heights of Sineru and the rest. The mountains stand all round Sineru, enclosing it, as it were. Yugandhara surrounds Sineru, then Īsadhara surrounds Yugandhara, and likewise with the others” (Vism-mhṭ 199).

[15]:

[16]:

A-a commenting on A I 35 ascribes the Simbali Tree to the Supaṇṇas or winged demons. The commentary to Ud 5.5, incidentally, gives a further account of all these things, only a small portion of which are found in the Suttas.

[17]:

See note 14.

[18]:

The rendering of sadevamanussānaṃ by “with its princes and men” is supported by the commentary. See M-a II 20 and also M-a I 33 where the use of sammuti-deva for a royal personage, not an actual god is explained. Deva is the normal mode of addressing a king. Besides, the first half of the sentence deals with deities and it would be out of place to refer to them again in the clause related to mankind.

[19]:

The references are these: Apalāla (Mahāvaṃsa, p. 242), “Dwelling in the Himalayas” (Vism-mhṭ 202), Cūḷodara and Mahodara (Mhv pp. 7–8; Dīp pp. 21–23), Aggisikha and Dhūmasikha (“Inhabitant of Sri Lanka”—Vism-mhṭ 202), Āravāḷa and Dhanapālaka (Vin II 194–96; J-a V 333–37), Saccaka (MN 35 and 36), Ambaṭṭha (DN 3), Pokkharasāti (D I 109), Soṇadaṇḍa (DN 4), Kūṭadanta (DN 5), Āḷavaka (Sn p. 31), Sūciloma and Kharaloma (Sn p. 47f.), Sakka (D I 263f.).

[20]:

For the breaking up of this compound cf. parallel passage at M-a I 10.

[21]:

[22]:

The commentarial name for the Elder Sāriputta to whom the authorship of the Paṭisambhidā is traditionally attributed. The Paṭisambhidā text has “Buddha,” not “Bhagavā.”

[23]:

“The Niddesa method is this: ‘The word Blessed (bhagavā) is a term of respect. Moreover, he has abolished (bhagga) greed, thus he is blessed (bhagavā); he has abolished hate, … delusion, … views, … craving, … defilement, thus he is blessed.

“‘He divided (bhaji), analyzed (vibhaji), and classified (paṭivibhaji) the Dhamma treasure, thus he is blessed (bhagavā). He makes an end of the kinds of becoming (bhavānaṃ antakaroti), thus he is blessed (bhagavā). He has developed (bhāvita) the body and virtue and the mind and understanding, thus he is blessed (bhagavā).

“‘Or the Blessed One is a frequenter (bhajī) of remote jungle-thicket resting places with little noise, with few voices, with a lonely atmosphere, where one can lie hidden from people, favourable to retreat, thus he is blessed (bhagavā).

“‘Or the Blessed One is a partaker (bhāgī) of robes, alms food, resting place, and the requisite of medicine as cure for the sick, thus he is blessed (bhagavā). Or he is a partaker of the taste of meaning, the taste of the Law, the taste of deliverance, the higher virtue, the higher consciousness, the higher understanding, thus he is blessed (bhagavā). Or he is a partaker of the four jhānas, the four measureless states, the four immaterial states, thus he is blessed. Or he is a partaker of the eight liberations, the eight bases of mastery, the nine successive attainments, thus he is blessed. Or he is a partaker of the ten developments of perception, the ten kasiṇa attainments, concentration due to mindfulness of breathing, the attainment due to foulness, thus he is blessed. Or he is a partaker of the ten powers of Perfect Ones (see MN 12), of the four kinds of perfect confidence (ibid), of the four discriminations, of the six kinds of direct knowledge, of the six Enlightened Ones’ states [not shared by disciples (see note 7)], thus he is blessed. Blessed One (bhagavā): this is not a name made by a mother … This name, Blessed One, is a designation based on realization”’ (Vism-mhṭ 207).

[24]:

Here are explanations of those things in this list that cannot be discovered by reference to the index: The pairs, “anger and enmity” to “conceit and negligence (M I 16). The “three roots” are greed, hate, and delusion (D III 214). The “three kinds of misconduct” are that of body, speech, and mind (S V 75). The “three defilements” are misconduct, craving and views (Ch. I.9,13). The “three erroneous perceptions” (visamasaññā) are those connected with greed, hate, and delusion (Vibh 368). The three “applied thoughts” are thoughts of sense-desire, ill will, and cruelty (M I 114). The “three diversifications” (papañca) are those due to craving, conceit, and [false] views (XVI n. 17). “Four perversenesses”: seeing permanence, pleasure, self, and beauty, where there is none (Vibh 376). “Four cankers,” etc. (XXII.47ff.). “Five wildernesses” and “shackles” (M I 101). “Five kinds of delight”: delight in the five aggregates (XVI.93). “Six roots of discord”: anger, contempt, envy, fraud, evilness of wishes, and adherence to one’s own view (D III 246). “Nine things rooted in craving” (D III 288–89). “Ten courses of unprofitable action”: killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, slander, harsh speech, gossip, covetousness, ill will, wrong view (M I 47, 286f.). “Sixty-two kinds of view”: (D I 12ff.; MN 102). “The hundred and eight ways of behaviour of craving” (Vibh 400).

[25]:

Abhigamanīya—“fit to be relied on”: abhigacchati not in PED.

[26]:

Vism-mhṭ says the word “etc.” includes the following six: mahimā, patti, pākamma, īsitā, vasitā, and yatthakāmāvasāyitā. “Herein, aṇimā means making the body minute (the size of an atom—aṇu). Laghimā means lightness of body; walking on air, and so on. Mahimā means enlargement producing hugeness of the body. Patti means arriving where one wants to go. Pākamma means producing what one wants by resolving, and so on. Isitā means self-mastery, lordship. Vasitā means mastery of miraculous powers. Yatthakāmāvasāyitā means attainment of perfection in all ways in one who goes through the air or does anything else of the sort” (Vism-mhṭ 210). Yogabhāåya 3.45.

[27]:

The three “abidings” are these: heavenly abiding = kasiṇa jhāna, divine abiding = loving-kindness jhāna, etc., noble abiding = fruition attainment. For the three kinds of seclusion, see IV, note 23.

[28]:

Vism-mhṭ adds seven more plays on the word bhagavā, which in brief are these: he is bhāgavā (a possessor of parts) because he has the Dhamma aggregates of virtue, etc. (bhāgā = part, vant = possessor of). He is bhatavā (possessor of what is borne) because he has borne (bhata) the perfections to their full development. He has cultivated the parts (bhāge vani), that is, he has developed the various classes of attainments. He has cultivated the blessings (bhage vani), that is, the mundane and supramundane blessings. He is bhattavā (possessor of devotees) because devoted (bhatta) people show devotion (bhatti) to him on account of his attainments. He has rejected blessings (bhage vami) such as glory, lordship, fame and so on. He has rejected the parts (bhāge vami) such as the five aggregates of experience, and so on (Vism-mhṭ 241–46).

As to the word “bhattavā”: at VII.63, it is explained as “one who has frequented (bhaji) attainments.” In this sense the attainments have been “frequented” (bhatta) by him Vism-mhṭ (214 f.). uses the same word in another sense as “possessor of devotees,” expanding it as bhattā daḷhabhattikā assa bahu atthi (“he has many devoted firm devotees”—Skr. bhakta). In PED under bhattavant (citing also Vism 212) only the second meaning is given. Bhatta is from the same root (bhaj) in both cases.

For a short exposition of this recollection see commentary to AN 1:16.1.