Shukra Niti by Shukracharya

by Benoy Kumar Sarkar | 1914 | 106,458 words

The English Translation of the Shukra Niti by Shukracharya: An ancient Sanskrit text possibly dating to the 4th-century BC. The text contains maxims that deal with politics, statecraft, economis and ethics and shed light on the social life, monarchy and government of ancient India as well their knowledge of early political science....

Chapter 4.7 - The Army

[This is a purely political chapter embracing many of the important topics dealt with in Treatises on International Law, especially in their sections on War.]

1. Forts have been briefiy discussed, the Seventh Section, that on the Army is now being narrated.

2. The army is the group of men, animals, &c., equipped with arms, missiles, &c

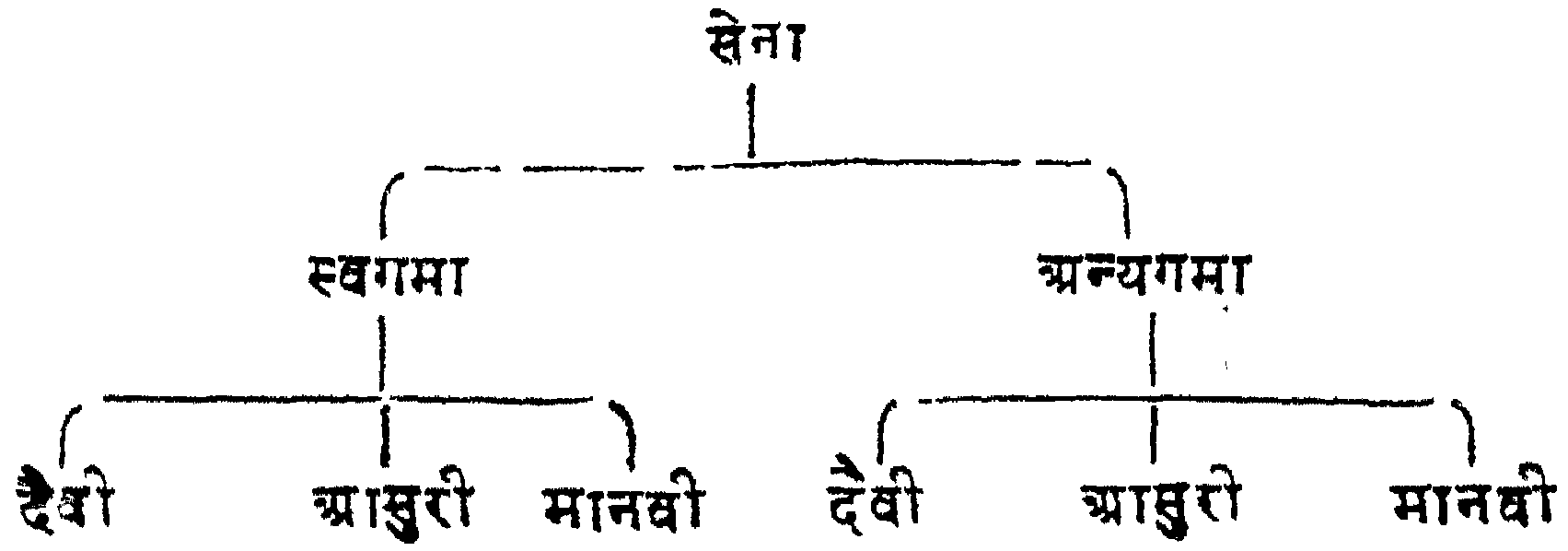

3-4.[1] The army is of two kinds: (1) that which proceeds independently; (2) that which has resort to vehicles, &c. Each, again, is of three kinds: (i) that pertaining to the gods; (ii) that pertaining to monsters; and (iii) that pertaining to human beings. The preceding ones are stronger than the succeeding.

5-6. The svagamā army is that which moves without any help, the anyagamā is that which proceeds in vehicles. The Infantry, is the the other is of three kinds, using chariots, horses or elephants.

7-8. Without the army there is neither kingdom, nor wealth nor prowess.

8-9.[2] Even in the case of a man of no position, everybody becomes his tool if he has strength and becomes his enemy if he be weak. Does not this hold true in the case of rulers?

10-12.[3] Strength of the body, strength of valour and prowess, strength of the army, strength of arms, fifth is strength of intelligence, the sixth is strength of life. One who has all these is equivalent to Viṣṇu.

13. Without the army no one can overpower even an insignificant enemy.

14.[4] The gods, monsters, as well as human beings have to depend on others’ strength (i.e., strength of the army).

15-16. The army is the chief means of overpowering the enemy. So the king should carefully maintain a formidable army.

17-18.[5] The army is of two kinds—one’s own, and that belonging to the allies. Each again is of two kinds according as it is—(i) long standing, or (ii) newly recruited, and also as it is—(i) useful, or (ii) useless.

19-20.[6] (The army is of two kinds): untrained or trained; officered by the State or not officered by the State; equipped by the state with arms, or supplying their own arms and ammunitions; bringing their own vehicles or supplied with vehicles by the State.

21. The army that belongs to the allies is maintained through good-will, one’s own army is however maintained by salary.

22. The maula army is that which has been existing for many years, the sādyaska, which is not that.

23. The sāra, efficient or useful army is that which is adapt in warfare, the contrary is the asāra.

24. The trained army is that which is skilled in the vyūhas or military tactics, the opposite is the untrained.

25. The gulmībhūta army is that which has officers of the State, (he agulmaka is that which brings its own chiefs,

26. The dattāstra army is that which receives arms etc. from the master, otherwise is the army which supplies its own arms and missiles.

27. The army regimented by the State, and the regiments formed among the soldiers by themselves; likewise the army receiving conveyances from the state (or not).

28.[7] The kirātas and people living in forests who are dependent on their own resources and strength (belong to the latter class).

29-30.[8] The troops left by, or captured from, the enemy and placed among one’s own people as well as one’s own troops tampered with by the enemy, should be regarded as inimical.

31. Each is weak, and not at all a help,

32-33.[9] Strength of the physique is to be promoted in the interest of hand-to-hand fights by means of tussles between peers, exercises, parades and adequate food.

34-35. The king should promote the strength of valour and prowess by means of hunting excursions against tigers (and big games) and exercises among heroes and valorous people with arms and weapons.

36-37.[10] The strength of the army is to be increased by good payments, that of arms and weapons by penances and regular exercises; and that of intelligence by ‘the companionship of (or intercourse with) people learned in Śāstras.

38-40.[11] The king should so govern his life that the kingdom may be permanent in his own dynasty through continuity of good deeds. So long as the kingdom continues in his family so long he is said to live.

41.[12] The king should have his infantry four times the cavalry, bulls one-fifth of his horse, camels one-eighth, elephants one-fourth of the camels, chariots half of elephants, and cannon twice the chariots.

45-6.[13] He should have in the army a predominance of footsoldiers, a medium quantity of horse, a small amount of elephant force, equal number of bulls and camels, but never elephants in excess.

47-53.[14] The ruler whose income is a lac karṣa or one lakh of rupees should have every year one hundred reserve force of the same age, well-accoutred and decently equipped with weapons and missiles, three hundred footsoldiers armed with lesser fire-arms or guns—eighty horses, one chariot, two larger fire-arms or cannons, ten camels, two elephants, two chariots, sixteen bulls, six clerks, and three councillors,

53-8.[15] The ruler should every month spend one thousand and five hundred rupees on contingencies, charities and personal wants, one hundred on the clerks, three hundred on councillors, three hundred on wife and children, two hundred on the men of letters, four thousand on the horsemen, horses and infantry, four hundred on elephants, camels, balls, and fire-arms, and save the remaining one thousand and five hundred in the treasury.

59.[16] The ruler should annually withdraw money from the soldiers for their accoutrements.

60-63.[17] The chariot that is to be kept by the State should be made of iron, easily movable by means of wheels, placed on a platform, provided with a seat for the driver in the middle, filled with weapons and missiles in the interior, fitted up with arrangements for producing shade at will, beautiful to look at, and furnished with good horses.

64-67.[18] Harmful elephants are those that have blue palates, blue tongues, curved tasks, or no tusks, who persist long in their angry moods, whose rut gushes out without any systematic order, who shake their backs, who have less than eighteen nails, and whose tails touch and sweep the ground; good elephants have the opposite attributes.

68.[19] There are four classes of elephants—Bhadra, Mandra, Mṛga and Miśra.

69-70. The Bhadra elephant is known to be that which has tusks coloured like honey (i.e., not pure white but yellowish), which is strong and well-formed, is round and fat in body, has good face and has excellent limbs.

71-72.[20] The Mandra elephant is that which has a fat belly, lion-like eyes, thick skin, thick throat and thick trunk, medium limbs and a long body.

73-74. The ‘Mṛga’ elephant is that which has small or short throat, tusks, ears and trunk, big eyes, and very short lips and genital organ, and is dwarf.

75.[21] The ‘Miśra elephant is that which has these characterising in mixture.

76.[22] The three species have separate measurements.

77-78. In elephant measurements one aṅgula is made by eight yavodaras, and one kara or cubit is made by twenty-four aṅgulas.

7 9-80. In the Bhadra class the height or stature is seven cubits, the length is eight cubits, and circumference of the belly is ten cubits.

81.[23] The measurement of the Mandra and Mṛga species are successively one cubits less than the preceding.

82.[24] But it is mentioned by sages that the lengths of the Mandra and Bhadra class would be equal.

83-84.[25] The best of all elephants is that which has long cheeks, eyebrows and forehead, has the swiftest speed, and has auspicious marks on the body.

85.[26] The horse measure is separate, as indicated by the ratio that five Yavas make one aṅgula.

86-89.[27] The best horse is that whose face is twenty-four aṅgulas. The good is that whose face is thirty-six aṅgulas. The medium is that whose face is thirty-two aṅgulas. The inferior is that whose face is twenty-eight aṅgulas.

90. In horses all the limbs are made according to a certain proportion with the face.

91-95.[28] The height is three times the measure of the face. The length of the whole body from the crescent (top of the head) to the beginning or origin of the tail is four times the face together with its one-third. The circumference of the belly is three aṅgulās over and above three times the face. These are the general rules of measurement of limbs. Elaborate details are being given below.

96-101.[29] In the horse of the twenty-eight-aṅgula-face, the height of the heel (hoof) is three aṅgulas, the ankle-joint (fetlock) four aṅgulas, the leg is twenty aṅgulas, the knee is three aṅgulas, the thighs to the end of the elbow are twenty-four aṅgulas. The space from the elbow-joint to the neck is thirty-eight aṅgulas. The back things are equal to the face, the back legs are less than the face by a quarter.

102. The height has been already mentioned. The length is now being described according to the Śāstras.

103-104.[30] The length of the neck is extensive, one-sixth in addition to twice the face. The height of the neck is one-fourth and half of that less than the face.

105-106.[31] From the end of the neck to the origin of the genital organ the measure is equal to that of the neck. From there to the end of the vertebral column the space is one-half and one-sixth of the face.

107-108. The tail is half the face, the genital organ likewise, the testicles are half the tail and organ. The ear is six aṅgulas long, may be four or five aṅgulas also.

109-110. The circumference of the heel or hoof is one aṅgula in addition to half the face. That of the portion just above is half of this, that of the legs is likewise.

111-113. The circumference of good thighs is eleven aṅgulas according to the masters. The circumference of the back thighs is three times onesixth. The outer aspect of the hind thigh and leg is to look like a curved bow.

114-115. The circumference of the hock at the ankle-joint is nine aṅgulas. The circumference of the hind legs is equal to that of the forelegs.

116-117. Space between two thighs is one aṅgula. Breadth or width of the neck on which the hair grows is one and a half aṅgula.

118-119. The mane should be made to grow beautifully downwards, to the extent of one cubit, from the space between the crown and the end of the neck.

120-122. The hair of the tail is one and a half cubit or two cubits. The length of the ears is seven, eight, nine or ten aṅgulas, their width is three or four aṅgulas.

123-125. The neck is neither fat nor flat but like that of the peacock. The circumference of the foreneck is one muṣṭi or four aṅgulas in addition to the face. The circumference of the origin of the neck where it comes out from the body) is twice the face minus ten aṅgulas.

126-127. The good breast is one-third less than the face. The circumference of the forehead over the eyes is eight aṅgulas in addition to the face.

128-129. The circumference of the face at the nose below the eye is equal to the face minus one-third.

130-131. The width of the eye is two aṅgulas, their length is three aṅgulas. Or the width two aṅgulas and a half and the length is four aṅgulas.

132. The space between two thighs is one-third face.

133. The space between the two eyes is one-fifth of the face.

134. The space between two ears is likewise, as well as the space between an eye and an ear.

135. The space between two heels, when the horse is standing erect is qeual to the length of the ear.

136-7.[32] The space between two eye-pupils, space between two eyes, as well as the space between the nose and the eye are one-third of the hind thigh-

138-9. The upper lip is one third of the face. The space between two nostrils is one-ninth of the same.

140. The body (from back to breast) is half of human height, and is equal to the breast at the end of the vertebral column.

141. The breast hangs low at the origin of the arms to the extent of one-fourth of the face.

142-3. The space between the arms at the breast is known to be onesixth of the face. The lower lip is an aṅgula and a half high together with the jaw,

144. That horse is beautiful which has a high neck and low back.

145-7.[33] If an image is to be made, the appropriate pattern or model should be always placed in front. No image can be made without a model. So the artist should frame the limbs after meditating on the horse and finding out the measurements and attributes of horses in the manner indicated above.

149-53. The horse with divine attributes or excellent horse is that which has a beardless face, beautiful, smart and high nose, long and high neck, short belly, heels and ears, very swift speed, voice like the cloud and the gander, is neither very wicked nor very mild, has good form and colour and beautiful circular rings of feather.

154-55. Circular hair-rings or feather-rings are of two kinds—those turning leftwards or rightwards, full rings or partial rings, small rings or large rings.

156-57.[34] The hair ring that turns leftwards is auspicious in the female horse, and that which tarns rightwards in the male horse. Not the contrary.

158. Their results vary with the directions in which they are formed, e.g., downwards, upwards or oblique.

159-61.[35] The auspicious marks made of hair or feather are the conch, wheel; mace, lotus, altar, seat of meditation, palace, gate, bow, pitcher full of water, white mustard seeds, garland, fish, dagger and Śrīvatsa gem.

162-63. Those horses are the very best which have these feathery shapes on the nose-tip, the forehead, throat and head.

164-65. Those are good horses which have these hair marks on the breast, neck, shoulder, waist, nave, belly and the front of the sides.

166-67. The ‘pūrṇaharṣa’ horse is that which has two such marks on the brow and a third on the head.

168-69. The horse that has a mark on the backbone leads to the increase of the master’s horses and is known as the ‘sūrya’ horse.

170-71. The horse that has three marks on the forehead is known as ‘trikūṭa’ and leads to the increase of horses.

172-73. The horse that has three such feather spots on the neck is the ‘vājīśa’ or lord of horses in the royal stable.

174-75. If two marks are noticed on the cheeks of a horse they lead to the increase of fame and kingdom.

176-77. The horse that has however only one mark on the cheek is known as the ‘sarvanāma’ and leads to the owner’s ruin.

178-79. The horse that has a mark on the right cheek is known as the ‘śiva’ and leads to the happiness of the master.

180. The horse that has a mark on the left cheek is wicked and leads to loss of wealth.

181-83. The horses that have two spots on the ears are known as ‘Indra’ those that have marks on the nipples are known as ‘Vijaya’

Both give victory in wars and lead to the increase of territory.

184-85. The horse that has two marks on the side of the neck is known as ‘Padma’ and that brings several Padmas (Padma—one thousand billions) of wealth as well as unceasing happiness to the master.

186-87. The horse that has one or three marks in the nose in known as ‘Bhupala [Bhūpāla]’ and ‘Cakravartī’.

188-89. The horse that has one large mark on the throat is known as Cintāmaṇi and leads to the realisation of the desired objects.

190. The horses that have marks on the forehead and the throat are known as Śulka and give increase and game.

191-2. If the horse has marks in the mouth or at the end of the belly, it is sure to get death or causes ruin of the master.

193-95. The marks that are on the knees give the troubles of life abroad. That on the genital organ causes loss of victory and beauty. That on the end of the vertebral column means destruction of trivarga, i.e., every thing.

196-97. The horse that has a mark on the origin of the tail is ruinous and known as Dhūmaketu. The horse that has a mark on the rectum, the tail and the end of the vertebral column is known as the Kritānta [Kṛtāṅta?].

200-2. The marks are always bad if they are on eyes, jaws; cheeks, breast, throat, upper lip, kidney, waist, knee, genital organ, hump of the back, navel, right waist and right foot.

203-5. The marks are good if they are on the throat, the back, lower lip, space between ear and eye, left waist, sides, thighs, and fore legs.

206-7. Two marks on the forehead with space between indicate good and are like the sun and the moon. If they overlap they give medium results, but if they are too contiguous they are evil.

208-9. Three marks on the forehead with space between them one being on the top are indicative of good. But two marks very contiguous to each other are inauspicious.

210. Three triaṅgular marks on the forehead are the causes of grief.

211. One mark in the middle of the throat is very auspicious and prevents all harms.

212. On the leg the downward mark is good, on the forehead the upward.

(?)213. A Śatapadī which is turned backward is not all regarded as inauspicious.

214-15. The mark on the back of the genital organ or the nipple is bad. That near the ear also is bad.

216. If the horse has a mark on one of the upper sides of the neck it is called Ekaraśmi.

217. The horse that has an upward mark on the leg is disparaged as the uprooter of posts.

218. The horse that has both good and evil marks is known to be medium.

219.[36] The horse that has five white marks on the face and four on legs is known as Pañcakalyāṇa, The one that has in addition to these three marks on the breast, neck and tail is known as Aṣṭamaṅgala.

220. The Śyāmakarṇa horse is that which has one colour throughout the body but has ears coloured śyāma i.e., greenish. If that one colour be white the horse is sacred and deserves to be worshipped.

223. The horse is known to be Jayamaṅgala which has eyes like vaiduryya [vaiḍūrya] gem.

224. The horse may be worshipped, whether of one colour or of variegated colour, provided it is beautiful.

225. The horse with black legs as well as that with one white leg are disparaged.

226-28. The rough, grey coloured as well as ash-coloured horses are also despised. The horses with black roofs of mouth, black tongues, black lips, as well as those which are throughout black but have white tails are deprecated.

229-31. Those horses are good which run with legs thrown from a height, whose movements are like those of tigers, peacocks, ducks, parrots, pigeons, deer, camels, monkeys and bulls.

232-33. If the horse-man does not get tired by riding a horse even after over-feeding and over-drinking, the gait of the horse is known to be excellent, and the horse is also very good.

234-35. The horse that has one very white mark on the forehead but is throughout coloured otherwise is known as dala-bhañjī the man who has such a horse is looked down upon.

230. All defects due to colour vanish if the horse has a decent aspect.

238. The horse that is strong, has good gait, is well-formed and not very wicked is much appreciated even if defiled by hair-marks.

239-43.[37] Defects grow in horses through long continued absence of work. But through excessive work the horse grows lean and emaciated by disease. Without bearing burden the horse becomes unfit for any work, Without food it becomes sickly, but with excessive feeding it contracts disease. It is the good or bad qualifications of the trainer that give the horse good or bad gait.

244-45. The good trainer is he who moves his legs below the knees, keeps his body erect, is fixed in his seat, and holds the bridle uniformly.

246-47.[38] The good trainer should strike the horse at the proper place by whips mildly and not too severely but with medium pressure.

248-50. He should strike the horse at the sides if it neighs, also at the sides if it slips, at the ear if it shies, at the neck if it goes astray, at the space between the arms if angry, at the belly if absent-minded.

251. The horse is not struck at any other place by experts.

252-54. Or one should strike the horse at the breast if it be terrified, at the neck if it neighs, at the posterior if it slips, at the mouth if going astray, at the tail if it be angry, at the knees if it be absent-minded.

255-57. One should not strike the horse very often or at the wrong place. One adds to the defects of the horse by striking it at the wrong time and place. Those defects exist so long as the horse lives.

258. One should overpower the horse by whips, and should never ride a horse without a whip.

259.[39] The good horse should go one hundred dhanus in sixteen mātrās.

260. Horses are inferior according as their speed is lower (than the rate defined above.)

261-63. The circle that is to be made for training the horse is of the highest class if one thousand cāpas in circumference, is medium if half that size; inferior if half that, small if only one hundred dhanus in size, and very small if half that.

264-65.[40] The trainer should daily increase the movement or speed of the horse by exercises within the circular ring in such a way that it can run one hundred yojanas in a day.

266-67. One should ride the horse in the morning and evening in October and November, winter and spring, in the evening in summer, in the morning in autumn.

268. One should not use the horse in the rainy season nor on uneven grounds.

269. The appetite, strength, prowess and health of the horse are promoted by well-regulated movements.

270-71. The horse that has got fatigue through work should be given a slight stroll for sometime, then should be fed upon sugar and powdered grains mixed with water

272-73. The horse should be given peas or grains, māṣa, mung, both dry and wet, as well as well-cooked meat.

274. One should not use the whip at the places which have been wounded.

275-78. In the interest of its strength the horse should be given gut and salt just after work before the saddle and fittings are brought down.. Then when the sweat has disappeared and it has stood calm and quiet the horse should be relieved of its fittings and reins.

279-80. The horse should be made to stroll in the dust after its limbs have been rubbed, and carefully tended with baths, drinks and foods.

281. Wines and juices of forest or wild animals take away all the defects of horses.

282. The horse should be made to take milk, ghee, water and powdered grains.

283-84. If the horse be made to carry burden just after taking food and drink, it soon contracts coughs and gasps and other diseases.

285-86.[41] Barley and pea constitute the best food for horses, māṣa and makuṣṭha [makuṣṭhaka] are good, masur and mungs are inferior stuff.

287-88.[42] The movements of horses are of six kinds—dhārā, āskandita, recita, pluta, dhauritaka [dhaurītaka], valgita [balgita]; each has it own characteristics.

289. The dhārā gait is known to be that which is very fast, in the midst of which a horse would get puzzled if spurred with the heels.

291-92. The āskandita movement of horses is known to be that in which the horse contracts its forelegs and runs with rapid leaps.

293. The recita movement is that with short leaps but continuous.

294. The pluta movement is that in which the horse leaps with all the four legs like the deer.

295-96. The dhauritaka [dhaurītaka] movement is rapid movement with uncontracted legs very useful in drawing chariot.

297-98. The valgita [balgita] movement is that in which the horse runs with contracted legs, neck raised like that of the peacock, and half the body trembling.

299-300. In bulls the circumference of the belly is four times that of the face, the height or stature together with the hump is three times the face and the length is three times and a half of the face.

301. The bull that is seven ‘tālas’ in height is appreciated if possessing all these attributes.

302-3. The bull that is neither idle nor wicked but a good beast for carrying burden, has a well-formed body and a good back, is the best of all.

304-5. The camel that is strong-built, has a good face, is nine ‘tālas’ in stature, carries burden and goes thirty ‘yojanas’ a day, is appreciated.

306-7. The age of one hundred years is the maximum for men and elephants.

307. The young age of both men and elephants extends up to the twentieth year.

308-9. The middle age of man extends up to the sixtieth year, that of elephants to the eightieth.

310-1. The maximum age of horses is thirty-four years. That of bulls and camels is twenty-five years.

312-3.[43] The young age of horses, bulls and camels extends up to the fifth year. Their middle age extends up to the sixteenth year, old age since then.

314. The age of both bulls and horses is to be known from the growth and colour of teeth.

315-20.[44] In the first year of horses six white teeth grow. In the second year the lower teeth get black and red. In the third year both the front teeth become black and this goes on till the sixth year. In the fourth year the two teeth by the side of the two front teeth are replaced by new teeth. In the fifth year the last two (molar) teeth are replaced and these blacken from the sixth year.

321-24. The teeth gradually yellow from the ninth year and whiten from the twelfth year, become transparent like glass from the fifteenth year, have the hue of honey from the eighteenth year and of conch from the twenty-first year. The last continues till the twenty-fourth.

325.[45] Since twenty-fourth year the teeth get loose and separated, and begin to fall down in threes.

326-27. The horse that has attained full age gets three circular rows on the upper lip. The age is to be considered low in proportion as the rows are less.

328-29.[46] The bad horses are those that throw kicks, make sounds with lips, shake their backs, tend to go down into water, suddenly stop in the midst of a movement, lie down on the back, move backwards and leap up.

330. As well as those that have snake-like tongues, the colour of bears, ànd are timid in character.

331.[47] The horse that has a mark on the forehead disfigured by a minute blot (of another colour) is depreciated, as well as that which tears asunder the ropes.

332-35. All the eight white teeth of bulls grow in their fourth year. Two extreme (molar) teeth fall down and are replaced in the fifth year: in the sixth year the next two, in the seventh the next two, and in the eighth the central two.

336-37.[48] Every two years the teeth get black, yellow, white, red and conch-like in order. Then their looseness and fall commence.

338.[49] The age of camels also has to be understood from consideration like these.

339-40. The hook with two months, one for movement forward and the order for movement backward has to be used in controlling the elephant. The driver should use this instrument for regulating the movements of the animal.

341-44. [Description of the bridle or reins]. The horse is to be controlled by such a bridle.

345.[50] The bull and the camel have to be governed by strings with which the nose can be pulled.

346. An instrument with seven sharp teeth is to be used in cleansing (or rubbing) these animals.

347-48. Men as well as beasts have to be always governed by adequate punishments. The soldiers have to be controlled by special methods not by fines.

349-50. The horses and bulls are well kept in watered lands, the camels and elephants in forests, the foot soldiers in ordinary or public places.

351. The ruler should station one hundred soldiers at every yojana.

352-53.[51] The elephant, the camel, the bull, the horse are excellent beasts of burden in the descending order. Carriages are the best of all conveyances except in the rainy season.

354-55. The ruler should never proceed with a small army even against an insignificant enemy. The wise should never use the very raw recruits even though they are in great numbers.

356-57.[52] The untrained, inefficient and the raw recruits are all like bales of cotton. The wise should appoint them to other tasks besides warfare.

358-59.[53] The weak ones desert the fields when they fear loss of life. But the strong ones, who are capable of causing vikāra or flight, do not.

360-61. The man who has no valour cannot stand a fight even if he has a vast army. Can he stand the enemy with a small one?

362-63. The valorous man however can overpower the enemy with a small but well-trained army. What can he not achieve if he has a large army (at his back)?

364-65. The king should proceed against the enemy with the standing or old, trained and efficient troops. The veteran army does not desire to leave the master even at the point of death.

366-67. Alienation (of soldiers) is caused by harsh words, diminution of wages, threats, and constant life and work in foreign lands.

368-69. Since there can be no success if the army be disaffected, one should always study the causes of disaffection or alienation of the army belonging to oneself and also to the enemy.

370-71. The king should always by gifts and artifices promote alienation or disaffection among the enemy’s troops.

372-73. One should satisfy the very powerful enemy by service and humiliation, serve the strong ones by honours and presents, and the weak ones by wars.

374.[54] He should win over the equals by alliance or friendship and subjugate all by the policy of separation.

375. There is no other means of subjugating the foe except by causing disaffection among their soldiers.

376-77.[55] One should follow nīti or the moral rules so long as one is powerful. People remain friends till then; just as the wind is the friend of the burning-fire.

378-79. Deserters from the enemy should not be placed near the main army. They have to be employed separately (in other works) and in wars should be used first.

380. The allies’ troops may be placed in the front, at the back or the wings.

381-82. Astra is that which is thrown or cast down by means of charms, machines or fire. śastra is any other weapon, e.g., sword, dagger, kunta, &c.

383-85.[56] Astra is of two kinds, charmed or tubular. The king who desires victory should use tubular where the charmed does not exist, together with the śastras.

386-87. People expert in military instruments know of diverse agencies named astras and śastras varying according to short or large size and the-nature and mode of the sharp edges.

388. The ‘nālika’ (tubular or cylindrical) astra is known to be of two kinds according to large or small size.

389-94.[57] The short or small ‘nālika’ is the cylindrical instrument to, be used by infantry and cavalry, having an oblique (horizontal) and straight (perpendicular) hole at the origin (breech), the length of five vitastis (two cubits and a half), a sharp point (tila) both at the forefront (muzzle) and at origin, which can be used in marking the objective, which has fire produced by the pressure of a machine, contains stone and powder at the origin has a good wooden handle at the top, (butt) has an inside hole of the breadth of the middle finger, holds gunpowder in the interior and has a strong rod,

395-96.[58] The instrument strikes distant objects according as the bamboo •or bark is thick and hollow and the balls are long and wide.

397-99.[59] The large ‘nālika’ is that which has a post or wedge at the origin or breech, and according to its movements, can be pointed towards the aim, has a wooden frame and is drawn on carriage; if well used, it leads to victory,

400-404.[60] Five palas of suvarci salt, one pala of sulphur and one pala of charcoal from the wood of arka, snuhi and other trees, burnt in a manner that prevents the escape of Smoke, e.g., in a closed vessel have to be purified, powdered, and mixed together, then dissolved in the juices of snuhi, arka and garlic, then dried up by heat, and finally powered like sugar. The substance is gunpowder.

405-406.[61] Six or four parts of suvarci salt may also be used in the preparation of gunpowder. Sulphur and charcoal would remain the same.

407-408.[62] The balls are made of iron with other substances inside or without any such substance. For lesser nālas or guns the balls are made of lead or any other metal.

409-410. The nālāstras may be made of iron or of some other metal, have to be rubbed and cleansed daily and covered by armed men.

411-15.[63] Experts make gunpowders in various ways and of white and other colours according to the relative quantities of constituents:—charcoal, sulphur, suvarci, stones, haritāla lead, hingul [hiṅgula], iron filings, camphor, jatu, indigo, juice of sarala tree, &c.

416-17. The balls in the instruments are flung at the aim by the touch of fire.

418-421. The instruments has to be first cleaned, then the gunpowder has to be put in, then it is to be placed lightly at the origin of the instrument by means of the rod. Then the ball has to be introduced, then the gunpowder at the ear. Fire is next to be applied to this powder, and the ball is projected towards the objective.

422-23. The arrow is to be two cubits in length and to be so arranged that it can pierce the object when flung from the bow-string.

424. The mace is to be octagonal (in shape), to have a strong handle, and high up to the breast.

425. The paṭṭīśa is long as the human body, has sharp edges on both sides, and a handle.

426. The ekadhāra is slightly curved and four aṅgulas in width,

427. The kṣuraprānta is high to the navel, has a strong first, and the lustre of the moon.

428. The dagger is four cubits, has a rod as the handle and is edged like the razor.

429. The kunta is ten cubits flat and has a handle like śaṅku or stick.

430.[64] The wheel is six cubits in circumference, has razor-like edge and a good centre.

431. The pāśa is a rod, three cubits long, with three sharp needles, and an iron rope.

432-33. The kavaca or armour is the protection for the upper limb, has the helmet for covering the head, is made of iron sheet about the thickness of wheat.

434. The karaja is a strong arm that is made of iron and has a keen edge.1

435-37. The king who is provided with good supplies, is endowed with the ‘six attributes’ of Statecraft, and equipped with sufficient arms and ammunitions, should desire to fight. Otherwise he gets misery and dethroned from the kingdom.

438-39.[65] The affair that two parties, who have inimical relations with each other, undertake by means of arms to satisfy their rival interests is known as warfare.

440-41. The daivia warfare is that in which charms are used, the āsura that in which the mechanical instruments are used, the human warfare that in which śastras and hands are used.

442-3. There may be a fight of one with many, of many with many, of one with one, or of two with two.

44445. The ruler who wants to fight should carefully consider the season, the region, the enemy’s strength, one’s own strength, the fourfold policy and the six attributes of Statecraft.

446-48. The autumn, hemānta (October and November) and winter are the best seasons for warfare. The spring is good, the worst is the summer. In the rainy season war is not at all appreciated, peace is desirable then.

449-50.[66] When the king is well provided with military requirements and master of a sufficiently strong army, the season is soul-inspiring and foreboder of good.

451.[67] If very urgent business arise the season is not auspicious.

452. One should place the Lord of the universe in the heart (when going out on an expedition).

453.[68] There are no rules about time or season in cases created by the killing of cows, women and Brahmans.

454-55.[69] That country is excellent in which there are facilities for the regular parade and exercises of one’s own soldiers at the proper time but there are none for those of the foe.

456-57. That country is said to be good which provides equal facilities for military exercises to the troops of both parties in a contest.

458-59.[70] That region is the worst in which the enemy’s troops get ample grounds for parade and exercise but one's own troops get none.

460-61. If the enemy's army be one-third less than one’s own troops or untrained, inefficient and raw recruits, the circumstances would lead to success.

462-63.[71] One’s own army that has been maintained as children, and rewarded by gifts and honours and is well supplied with war provisions does lead to victory.

464-65.[72] The six attributes of statecraft are known to be peace, war, expedition, taking cover or besieging, refuge, and duplicity.

466-67. Those action by which the powerful foe becomes friendly constitute sandhi or treaty. That should be carefully studied.

468-69. That is said to be vigraha or war by which the enemy is oppressed and subjugated. The king should study this with his councillors.

470. A Yāna is expedition for the furtherance of one’s own objects and destruction of the enemy’s interests.

471.[73] An āsana is said to be that from which oneself can be protected and the enemy is destroyed.

472. The āśraya or refuge is said to be that by which even the weak becomes powerful.

473.[74] The dvaidhībhāva is the stationing of one’s troops in several regiments.

474-75.[75] When the king has been attacked by a powerful enemy and is unable to counteract him by any means, he should desire peace in a dilatory manner.

476-77.[76] There is only one treaty or peace desired by people, that is, gifts. Everything else besides alliance is a species of gifts.

478-79. The aggressor never returns without receiving something because of his might, for without gifts there is no other form of peace.

480. Gifts should be given according to the strength of the adversary. Service should even be accepted, or the daughter, wealth and property may be given away.

481. In order to conquer enemies peace should be made even with one’s own feudatories.

482-83. Peace should be made even with the anāryas for (otherwise) they can overpower the ruler by attack.

484.[77] Just as a cluster of bamboos cannot be destroyed if surrounded by thick thorny trees, so the ruler should be like a bamboo surrounded by clusters.

486-87.[78] Peace should be made with the very powerful, war with the equal and expedition (aggression) against the weak; but to friends should be granted refuge as well as residence in forts.

488-89. The wise should make peace with the powerful if there be danger, and protect oneself at the proper time if the foes be many.

490-91.[79] There is no precedent or rule that war should be undertaken with a powerful enemy. The cloud never moves against the current of the wind.

492. Prosperity never deserts a man who bows down to the powerful at the proper time, just as rivers never leave the downward course.

494-95.[80] The king should never trust the enemy even after concluding peace. Thus Indra killed Vṛtra in days of yore during the truce time.

496-97.[81] One should commence warfare when one is attacked and oppressed by some body, or even only when one desires prosperity, provided one is well placed as regards time, region and army.

498-500. The king should surround and coerce the ruler whose army and friends have been lessened, who is in the fortress, who has come upon him as enemy, who is very much addicted to sense-pleasures, who is the plunderer of people’s goods, and whose ministers and troops have been disaffected.

501. That is known to be ‘vigraha’ any other thing is ‘kalaha’ or mere quarrel.

502-503. One with a small army should never undertake a ‘vigraha’ or engage in war with a valorous man backed by a powerful army. If, however, that be done, his destruction is inevitable.

504.[82] The cause of ‘kalahi’ or quarrel or contention is the exclusive demand (of rivals) for the same thing.

505. When there is no ether remedy ‘vigraha’ or war should be undertaken.

506-507.[83] ‘Yānas’ or expeditions are known by experts to be of five kinds—Vigṛhya, Sandhāya, Sambhūya, Prasaṅga, and Upekṣyā.

508-509. The ‘Vigṛhya’ expedition is known by masters proficient in the subject to be that in which the army proceeds by gradually over-powering groups of enemies.

510-11.[84] Or ‘Vigrihya’ [Vigṛhya] expedition is that in which one’s own friends fight with the adversary’s friends on all sides, and the main army proceeds against the enemy.

512-13.[85] The ‘Saudhūya’ expedition of the man desiring victory is that which proceeds after peace is made with certain supporters of the enemy.

514-15. The ‘Sambhūya’ expedition is that which proceeds under the king aided by feudatories skilled in warfare well equipped with physical and moral resources.

516-17.[86] The ‘Prasaṅga’ expedition is that which begins against a certain objective but incidentally proceeds against another.

518-19. The ‘Upekṣya’ expedition is that which neglects the enemy and retreats after encountering adverse fate.

520. If the king (is generous and) rewards (well), the army becomes attached to him though his conduct is unrighteous and he comes of a low family.

521-22. The ruler should pacify his own troops by gifts of rewards and should go ahead accompanied by heroic guards.

523.[87] In the centre should be placed the family, treasure and valuables.

524. He should always carefully protect his army.

525-26. The commander should inarch in well-arrayed regiments wherever difficulties arise on the way through rivers, hills, forests and forts.

527-28. If there be danger ahead the commander should march in the great ‘makara’ or crocodile array, or the ‘śyena’ or bird array which has two wings or the ‘sūci’ needle-array which has a sharp mouth.

529-31.[88] If there be danger behind, the śakaṭa (carriage) array, if on the sides the vajra (thunder) array, if on all sides the sarvatobhadra (octagonal) or chakra [cakra] (wheel) or ‘vyāla’ (snake) array. Or the array should be determined according to the nature of the region in such a way as to pierce the enemy’s array.

532-33.[89] None besides one’s own troops are to know the signs for the formation of battle-‘orders’ communicated by means of bugle sounds.

534-35. The wise should always devise diverse forms of battle array for horses, elephants and footsoldiers.

535-37. The king should order the soldiers aloud by signs of battle-order from a station on the right or left, in the centre or in the front.

538. Having heard those orders the troops are to carry out the instructions.

589-40. Grouping, expansion, circling, contraction, straight movement, rapid march, backward movement.

541-43. Forward movement in rows, standing erect, lying down, standing like octagon, wheel, needle, carriage, half moon.

544-45. Separation in parts, standing in serial rows, holding the arms and weapons, fixing the aim, and striking the objective.

546-47.[90] Flinging of missiles, striking by weapons, swift use of arms.

548-49. Self-defence, counteraction by movements of limbs or use of arms and weapons, movement in rows of two, three or four,

550.[91] Movement forward or backward or sidewards.

551. In throwing a missile, movement forward or backwards is necessary.

552. The soldier stationed in the battle-array should always fling the missile by moving forward.

553. Just after throwing the arm the soldier should sit down or move forward.

554-55. Having seen the enemy in the sitting posture the troops should cast their own arms by moving forward in ones or twos or groups as ordered.

559-57. The krauñca (pigeon) array is to be formed according to the nature of the region and the troops in the same rows as the movements of pigeons in the sky.

558.[92] It is that order in which the neck is thin; the tail medium, and the wings thick.

559. The śyena or bird order is that in which the wings are large, the throat and tail medium, and the mouth small.

560. The makara or crocodile order is that which has four legs, long and thick mouth and two lips.

561. The sūci or needle order has a thin mouth, is a long red and has a hole at the end.

562. The cakra array has one passage and has eight concentric rings.

563. The sarvatobhadra array is the battle order which lias eight sides in all directions.

564. The wheel array has no passage, has eight concentric rings and faces in all directions.

565.[93] The carriage-array has the aspect of a vehicle, and the snake array that of a snake.

566-67.[94] The ruler should devise one, two or more of these ‘vyūhas’ or a mixture of them according to the number of troops and the character of road and battle-fields.

568-569. One should lie with troops at those places whence the enemy’s army can be overpowered by arms and weapons The condition is called ‘āsana,’

570-571.[95] From the manoeuvre of ‘āsana’ one should destroy carefully those people who help the enemy by carrying wood, water and provisions.

572-573.[96] One should subjugate the enemy through protracted processes by which provisions are cut short, food and fuel are diminished, and the subjects are oppressed.

574-575. When in a war both the enemy and the aggressor have got tired they seek cessation from hostilities. The state is called ‘sandhāya āsana’ or truce,

576-577. When one has been overpowered by the enemy and does not find any remedy to counteract the defeat he should seek refuge with a powerful ruler who is truthful, honest, and has good family connexions.

578.[97] The friends, relatives and kinsfolk are the allies of the aggressors. Other rulers are either paid friends or sharers in the spoils of victory.

580.[98] That is said to be ‘āśraya’ as well as forts,

581-83.[99] When the ruler is not sure of the methods of work to be adopted, and is waiting for the opportune time, he should have resort to duplicity like the crow’s eye and display one move but really adopt another.

584-587. Even ordinary people get their desired objects through good methods, good policies, and persevering efforts, cannot the princes? A work can be successful only through efforts, not through mere wish Thus the elephant does not of itself enter the mouth of the sleeping lion.

588-90.[100] Even the hard iron can by proper methods be converted into a liquid. It is also a noted fact that water extinguishes fire. By the man who exerts, fire can be extinguished.

591. It is policy by which the feet can be placed on the head of elephants.

592.[101] Separation is the best of all methods or policies of work, and ‘samāśraya’ or refuge is the best of the six attributes of Statecraft. Both these ire to be adopted by the aggressor who wants success. Without these two the king should never commence military operations.

595-96.[102] He should adopt such means as lead to rivalry or conflitct between the Commander-in-chief and Councillors of the enemy, and strife among their subjects or women.

597-98.[103] One should always study the policies as well as six attributes of Statecraft concerning both parties, and embark upon a war if death or universal plunder have been the antecedent circumstances.

599. Even Brāhmaṇas should fight if there have been aggressions on women and priests or there has been killing of cows.

600. One should not desist from the fight if it has once commenced.

601. The man who runs away from battle is surely killed by the gods.

602-3. The king who protects subjects should in pursuance of the Kshatriya’s duties never desist from a fight if called to it by an equal, superior or inferior.

604-5.[104] The earth swallows the king who does not fight and the Brahman who does not go abroad, just as the snake swallows the animals living in the holes.

606-7.[105] The life of even the Brahman who fights when attacked is praised in this world, for the virtue of a Kṣatriya is derived also from Brahma.

608.[106] The death of Kṣatriyas in the bed is a sin.

609-10.[107] The man who gets death with an unhurt body by excreting cough and biles and crying aloud is not a Kṣatriya. Men learned in ancient history do not praise such a state of things.

612. Death in the home except in a fight is not laudable.

613.[108] Cowardice is a very miserable sin in valorous people.

614-15.[109] The Kṣatriya who retreats with a bleeding body after sustaining defeat in battles and is encircled by family members deserves death.

616-17. Kings who valorously fight and kill each other in battles are sure to attain heaven.

618-19. He also gets eternal bliss who fights for his master at the head of the army and does not shrink through fear.

620-21. People should not regret the death of the brave man who is killed in battles. The man is purged and delivered of all sins and attains heaven.

622-23.[110] The fairies of the other world vie with each other in reaching the warrior who is killed in battles in the hope that he be their husband.

624-25.[111] The great position that is attained by the sages after long and tedious penances is immediately reached by warriors who meet death in warfare.

626-27.[112] This is at once penance, virtue and eternal religion. The man who does not fly from a battle does at once perform the duties of all the four ‘āśramas’.

628-29. There is no other thing besides valour in all the three worlds. It is the valorous man who protects the universe, it is in him that everything finds its stay.

630-31. The immovables are the food of the mobiles, the toothless of the toothed creatures, the armless of the armed, the cowards of the valiant.

632-33.[113] In ibis world two men can go beyond the solar sphere (i.e., into heaven):—the austere missionary, and the man who is killed in the front in a fight.

634-35. One should protect oneself by killing even the learned Brahman and Guru in battle if they are inimical. This is the decree of Śruti or Vedas.

636-37.[114] The teachers are kind and the learned people are advocates of sinlessness. They should never be asked on occasions of great fear (e.g., warfare).

638-39.[115] Learned people are ornaments in places where they can discourse on diverse subjects, e.g., in palaces, assemblies and cloisters.

640-41.[116] Learned people are ornaments in those places where they can perform various intellectual feats before large audiences in the matter of Sacrifice, Military Science, &c.

642-45.[117] Learned people are ornaments also in the matter of finding out others’ defects, studying human interests, and managing elephants, horses, chariots, asses, camels, goats and sheep, in the matters connected with cattle, wealth, roads and Svayamvara, and in studying the defects of food and social practices.

646-48. One should disregard the “wise men” who extol the merits of the enemies, discover the purposes the adversary has in view, and without minding that destruction might befall the army (in case of war) should employ a (suitable) expedient that would destroy the enemy.

649-50. The Brāhmaṇa who appears with a murderous intent is as good as a Śudra. There can be no sin in killing one who comes with a murderous intent.

651-52.[118] One would not incur the sin of killing an embryonic child (i.e., an infant) if one kills even an infant who has come upon him with weapon in hand. It is otherwise that one really perpetrates that offence.

653-55.[119] The sin of killing a Brahman does not touch the man who treats like a Kshatriya and kills the Brahman that fights with arm in hand and does not leave the battle-field.

656-57. The rascal who flies from a fight to save his life is really dead though alive, and endures the sins of the whole people.

658-59. The man who deserts the ally or the master and flies from the battle-field gets hell after death, and while alive is cried down upon by the entire people.

660-61. The man who sees his friend in distress and does not help him gets disrepute, and when dead goes to bell.

662-63 The wicked man who deserts one that seeks refuge with him in confidence goes to eternal hell so long as there are the fourteen Indras.

664-65.[120] The Brāhmaṇas should kill the Kṣatriya when his practices are wicked. They do not incur sin even if they fight with arms and weapons in hand.

666-67. When again the Kṣatriyas have become effete, and the people are being oppressed by lower orders of men the Brāhmaṇas should fight and extirpate them.

668-69, The war with charmed instruments is the best, that with mechanical is good that with weapons inferior, that with hands is the worst.

670-71. That war with charmed instruments is known to be the best of all in which the foes are destroyed by arrows and other arms rendered powerful through being applied with charms.

672-73. The war with mechanical instruments leads to great destruction of the enemy in winch balls are flung at the objective by the application of gunpowder in cylindrical fire-arms.

674-75 The war with weapons is that generally undertaken in the absence of fire-arms and other missiles, in which foes have to be killed by the use of Kunta swords and other weapons.

676-77.[121] The war with hands, i.e., duel or hand-to-hand fight is that in which the adversary is overpowered by strong grasps and skilful attacks on the joints of limbs, &c., whether against or in line with the system of hair.

678-82.[122] Catching the hair by means of the left hand, throwing down on the earth by force, beating by the leg, i.e., kicking on the head, pressing at the breast by knees, severe beating on the brow by bael-like (heavy) físts, elbowing, constant slappings, and moving about to find cut the proper places of attack—these eight are the species of duelling.

683-84.[123] The Kṣatriya should be attacked by four of these species, the worst Kshatriya by five, the Vaiśya by six, the Sūdra by seven, and the mixed castes by all the eight.

685.[124] These methods have to be applied to the enemies, never to the friends.

686-88. One should commence fight with any enemy whose minister and army have got disaffected by placing the fire-arms both light and heavy in the fronts the infantry just behind them, the elephants and horses in the wings.

689-90. The first skirmish is to be commenced by commanders with half the army in the front and the wings so long as the region favourable for warfare is not acquired.

692-93.[125] The war should then be undertaken by ministers with troops conducted by ministers, then finally by the king at the risk of his own life with troops commanded by the king.

694-700.[126] One should carefully protect one’s hoops but extirpate the enemy’s, when they have got tired by long marches, or through hunger and thirst, when they are oppressed by disease, famine, hailstorms and thieves, when they have to suffer from impurities of mud and dirt in water-, when they are gasping for breath, when they are asleep or engaged in taking food, when they are not in contact with the ground (i.e. have mounted tree., etc, etc), when they are vacillating, when they are overpowered by fear of fire or attacked by wind and rain, and by such other dangers and difficulties,

701-2. Of all the dangers that are known by the wise to befall an army, the worst is Bheda (alienation or sepeparation, or estrangement).

703-4. Even the Maula or standing or old army, if disaffected, is a source of dubious strength to the king. What to speak of the sundry recruits under disaffection?

705. One should always study the fourfold policy, the sixfold attributes of statecraft and the secrets of oneself as well as the enemy.

706. The enemy has to be killed in wars whether conducted according to the rules of morality or against them.

707-11. The king should increase the salary of the officers about a quarter in beginning the expedition, cover his own body during the fight by means of shield and panoply, make the soldiers drink invigorating wines, and employ in the battle those heroes who are enthusiastic and are certain of the issue and extirpate the foes by fire-arms, daggers and troops.

712-15. The horseman has to be attacked by the Kunta sword, the charioteer and the man on the elephant by arrow, the elephant by the elephant, the horse by the horse, the chariot by the chariot, the infantry by the infantry, one by one, the weapon by the weapon, the missile by the missile.

716-21.[127] One who follows the duties of good people should not kill the man who is on the ground who is deformed, who has his hands arranged in the form of añjali (i.e., in the sign of humiliation), who is seated with hair dishevelled, and who says ‘I am yours,’ who is asleep, who’ is naked or unarmed, who is seeing others fight or is fighting with others, who is drinking water, taking food or busy with other matters, who is terrified, who retreats.

722. The old mail, the infant, the woman, as well as the king, when alone, are not to be killed.

723.[128] But there is no deviation from the path of morality if one kills other by appplying the prescribed methods.

721. These rules, however, apply only to warfares conducted according to the dictates of morality but not otherwise.

725. There is no warfare which extirpates the powerful enemy so much as the kūṭayudha or war conducted against the dictates of morality

726-27.[129] In days of yore the kūṭa warfare was appreciated by Rāma, Krishna [Kṛṣṇa], Indra and other gods. It was through kūṭa that Vāli [Bāli], Yavana, and Namuchi [Namuci] were killed.

728-30.[130] One should inspire confidence in the enemy by sweet smiling face, soft words, confession of guilt, service, gifts, humiliation, praise, good offices as well as oaths.

731. One should study the enemy’s defects with a mind sharp as the razor.

732-33.[131] The wise should place insult or humiliation in the front and honour or glory at the back in order to fulfil his desired object, It is folly to lose one’s object.

734-36. The king seated on a platform, should study the activities of troops. Those who are friends of the king and the State, and who understand the bugle’s sounds and signs of Battle orders should always supervise the parades and exercises of troops.

737. Having noticed that disaffection has spread among the army through the enemy, the king should remove that.

738-39.[132] The king should grant rewards of wealth, property or privileges to those troops by whom new deeds are performed in the order of their deserts.

740-41. The powerful should carefully coerce the enemy by stopping the supplies of water, provisions, fodder, grass etc. in an unfavourable region and then extirpate it.

742-45.[133] One should sedulously destroy the enemy’s troops by alienating them by gifts of counterfeit gold, and also by alluring them to sleep through acts of confidence after fatigue due to keeping up of nights, but not the army of their allies even though they are under the sway of vices.

746. One should never allow a territory very near ones own to be made over to another.

747-48.[134] One should commence military operations all on a sudden and withdraw also in an instant and fall upon the enemy like robbers from a distance.

749-50.[135] Silver, gold or other booty belong to him who wins it. The ruler should satisfy by giving them those things with pleasure according to the labour undergone.

751-52. Having thus conquered the enemy, the king should realise revenue from a portion of the territory or from the whole, and then gratify the subjects.

753-54. The king should enter the conquered city with the auspicious sound of the turyya [tūrya-maṅgala-ghoṣa] and protect like children the people thus won over and made one’s own.

755-56.[136] The king should appoint councillors to the study of statecraft according as it varies with time, place and circumstances and also as it is the beginning, middle or end, in order that they may find out the values of various policies and the methods of work.

758-59.[137] The officers of councillors are to explain the business to the Crown Prince. The Crown Prince is then to communicate the findings to the king in the presence of the councillors.

760-61.[138] The king is first to direct the Crown-Prince. Then he is to direct the ministers, they the officers.

762. The priest is to counsel the king about good and evil courses of action.

763-64.[139] The king should station the troops near the village but outside it. And there should be no relations of debtor and creditor between the village folk and the soldiery.

765. The goods that are meant for the army should be reserved for soldiers in their midst.

766. The troops must never be stationed at any one place for a year.

767. The king should manage the army in such a way that about a thousand can be ready for service in an instant.

768. The military regulations should be communicated to the soldiers every eighth day.

769-71. The troops should always forsake violence, rivalry, procrastination over State duties, indifference to injuries of the king, conversion, as well as friendship with the enemies.

772. They should never enter the village without a royal ‘permit.’

773-74. They should never point to the defects of their commanders, but should always live on friendly terms with the whole staff.

775.[140] They should keep the arms, weapons and uniforms quite bright (and ready for use).

776.[141] Food, water, a vessel measuring one ‘prastha’, and vessel in which food for many might be cooked.

777-78. “I shall kill the troops who will act otherwise. You should all show me the booty that you receive from the enemy.”

779-80. The king should always practise military parades with the troops, and strike the objective by means missiles at the stated hours.

781-82. The king should count the troops both in the morning and evening and study their caste, stature, age, country, village and residence.

783-85. The king should have recorded the period served, rate of wages and the amount paid, how much has been paid to servants by way of wages and and how much by way of rewards. He should receive the acknowledgments of their receipts and give them the forms specifying wages etc.

786-87. Full pay is to be granted to those who are trained soldiers. Half pay is to be given to those who are under military training.

788. One should extirpate the troops that have illicit connexions with evil-doers and enemies.

789-90. The King should find out those soldiers who are addicted to the king’s vices, enemies of virtues and are indifferent to the vices.

791. The king should always forsake the servants, who, though qualified are pleasure-seekers.

792-94.[142] In the inner appartments such men are to be appointed as are very trusthworthy. The are also to be appointed in the Spending Department. So also those who enjoy the confidence of the people are to be appointed for the external functions.

795. If appointed otherwise, they lead to compunction.

796-98.[143] These alienated councillors of the enemies and such of their officers as are perpetually dishonoured through the master’s vices, and are instrumental in serving one’s purposes should be maintained by good remuneration.

799. Those who have been alienated through cupidity and inactivity should be maintained by half remuneration.

800. The king should maintain by good remuneration the well qualified men who have been deserted by the enemy.

801-802. When a territory has been acquired the king should grant maintenance beginning with the day of capture (to the conquered king) half of it to his son and a quarter to his wife.

803-804.[144] Or he should pay a quarter to the princes if well qualified, or a thirty-second part.

805. He should have the remaining portion of the income from the conquered territory for his own enjoyment.

806-807. He should invest that wealth or its half at interest until it is doubled, but not beyond that limit.

808-809. The king should maintain the dispossessed princes for the display of his own majesty by the bestowal of honours if well-behaved but punish them if wicked.

810-11. The king should divide the whole day (of twenty-four hours) into eight, ten or twelve periods of watch according to the number of the watchmen, not otherwise.

812-813.[145] At the beginning the watchmen are to serve during the several periods in a certain order. In the second round the first is to serve last? and the others to precede him.

814-15.[146] Or again, in the same manner, the last may be asked to be on duty in place of the first (in the above case) and then at the last watch (of that day), and then on the next day one who comes in the order of the second etc., should finish his turn first and so on.

816. The king should always appoint more than four watchmen for the day.

817. He may also appoint many simultaneously according to the weight of business.

818. He should never appoint less than four watchmen.

819-22. Whatever have to be protected or instructed should be communicated to the watchman. Everything should remain before him, and he should keep the measured amount of gold and other valuables in the wooden apartment (or trunk) and at the expiry of his term should show that to his successor.

823. At intervals the watchmen have to be called aloud from a distance.

824-25. It is only when the king follows the rules laid down by the wise that he is respected by the people, not otherwise.

826-27. That man deserves sovereignty for life whose activities are regulated, who is good and restrained in his receipts and who gives up illicit incomes.

828-29.[147] The man who is unrestrained in his speech and deed, and who is always crooked to friends is forthwith dragged down from his position.

830-31.[148] Just as even the tiger and the elephant cannot govern the lion, the king of beasts, so all the councillors combined are incompetent to control the king who acts at his own sweet will.

832-33.[149] Those councillors are his servants and hence quite insignificant in the matter of governing him). The elephant cannot be bound by thousands of bales of cotton.

834-35, It is only the powerful elephant that can extricate an elephant from the mud. So also it is only a king who can deliver a king who has gone astray.

836-37.[150] The dignity and force that are possessed by even the lower servants of powerful princes cannot be attained by even the ministers of kings who are insignificant.

838-39.[151] The unity of opinion possessed by the Many is more powerful than the king. The rope that is made by a combination of many threads is strong enough to drag the lion.

840-41. One whose territory is small, who is the servant of the enemy, should never maintain a large army, but should always augment the treasury for the prosperity of his own children.

842-43.[152] He should take to food and bed in such a way as to allay hunger and promote sleep, otherwise he shall grow poor.

844. The king should always spend money according to the manner indicated above, not otherwise.

845-46. Those kings who are devoid of morality and power should be punished like thieves by the king who is powerful and virtuous.

847-48, Even the lesser rulers can attain excellence if they are protectors of all religions. And even the greater rulers get degraded if they destroy morality.

849-50. It is the king who is the cause of the origin of good and evil in this world. He is the best of all men who attains sovereignty.

851-52.[153] The science that was appreciated by the sages like Manu and others, had been incorporated by Bhārgava or Śukra in the form of twenty-two thousand Ślokas of ‘Nītisāra’.

853-54. The king who always studies the abridged text of Śukra becomes competent to bear the burden of State affairs.

855-56.[154] In the three worlds there is no other ‘Nīti’ like that one of the poet (Śukra). The poetical work (of Śukra) is the sole ‘Nīti’ for politicians, others are worthless (as political codes).

857-58. Those rulers who do not follow Nīti are unfortunate and go to hell either through misery or through cupidity.

Here end the Seventh Section that on the Army in the Fourth Chapter of ‘Śukranīti’ as well as the Fourth Chapter.

Footnotes and references:

[2]:

It is strength that converts foes into friends in the case of ordinary people or of a man who has few people i.e., of insignificant persons). So the king should always have strength, (i.e., the army) and never be weak.

[3]:

The man possessing all these six kinds of strength is certainly super-human.

[4]:

Everybody requires assistants.

[6]:

Two kinds of military recruitment are described here. The army of the State seems to have been divided into two classes:

(1) the Standing army which must have been trained, regimented gulmībhūta or officered and manned by the Military Department of the State), and supplied with weapons and conveyances at State expense.

(2) the, national army of volunteers or the Militia which must necessarily be raw recruits, untrained, unregimented (i.e., having their own captains and lieutenant,) and responsible for their own arms, accoutrements and conveyances.

It would thus appear that the maula army i.e., that which is connected with the State, as it were, through roots, or from the beginning, would correspond to the permanent standing army of the kingdom, and the sādyaska or new army improvised for the occasions to the national Militia enlisted by the methods of conscription or voluntary service.

[7]:

It appears that the array of the State may be recruited from, independent foresttribes who do not ordinarily acknowledge suzerainty of the neighbouring chief. They of course bring their fighting apparatus.

[8]:

bhedādhīna—brought under the policy of bheda one of the four celebrated methods of Statecraft recognised in Hindu Nīti Śāstras, When once the loyalty of the troops has been tampered with by the enemy and seeds of disaffctīon have been sown among them, there is no trust to be placed with them. The disaffected army is as good as the enemy’s (and should be ‘disbanded’).

[9]:

samaiḥ—Equals, peers.

niyuddha—tug-of-war, hand-to-hand tussles.

bāhuyuddhārtha [bāhuyuddha-artha]—Muscular strength is a desideratum for duels.

[10]:

In 11. 31-36 Śukrācārya has pointed out the proper method of developing the various kinds of military strength—(1) physical, (2) moral, (3) intellectual &c.

tapaḥ [tapas]—Mantras and penances are prescribed for warriors in the use of missiles and weapons in all Hindu Treatises on Polity. ‘Atharva Veda’ is the great and one of the first storehouses of these military charms and incantations.

[11]:

The king should try to perpetuate himself and thus augment the strength or longevity of his life. The method suggested is satkriyā—i.e., the performance of good deeds. Satkriyā leads to popularity of the king and maintenance of the State in the same family for long. Thus the king himself lives long through posterity.

[12]:

The relative proportion of the constituents of the Army according to ‘Śukranīti’;

| pādāta (Footsoldiers) | = 4 aśva (Horse). | |

| vṛṣa (Bull) | = ⅕ of aśva (Horse). | |

| kramelaka (Camel) | = ⅓ of aśva (Horse). | |

| gaja (Elephants) | = ¼ kramelaka | = 1/32nd of aśva (Horse). |

| ratha (Chariot) | = ½ gaja | = 1/64th of aśva (Horse). |

| bṛhannālīka [vṛhannālika] (Cannon i.e., artillery) | = 2 ratha | = 1/32nd of aśva (Horse). |

[13]:

Here is a general remark about the definite proportion stated above. The bulls and camels may be equal in amount, the particular injunction about elephants should be noted.

[14]:

The annual military establishment of the ruler worth Rs. 1 00,000 which is regarded as the ‘unit’ of political life is described in these lines. It provides for:—

(1). 100 pṛthak or separate i.e., reserve force.

(2). 300 Infantry with guns.

(3). 80 Horses.

(4). 1 Chariot.

(5). 2 Cannons.

(6). 10 Camels.

(7). 2 Elephants.

(8). 2 Chariots.

(9). 16 Bulls.

(10). 6 Clerks or Scribes.

(11). 3 Councillors.

[15]:

The monthly items of expenditure of the ruler worth one lakh have been given in these lines. The ‘unit’ of Disbursement in the annual budget gives the figures in the following schedule:

| Items. | Per month. Rs. | Per year. Rs. |

| (1) Personal wants, enjoyments and charities, etc. | 1,500 | 18,000 |

| (2) 6 Clerks or Scribes | 100 | 1.200 |

| (3) 3 Councillors | 300 | 3,600 |

| (4)Family | 300 | 3,600 |

| (5) Learning and education | 200 | 2,400 |

| (6) Horse and Foot | 4,000 | 48,000 |

| (7) Elephants, Camels, Bulls and Fire-arms | 400 | 4,800 |

| (8) Savings | 1,500 | 18,000 |

| Total | 8,300 | Total 99,600 (about a lakh). |

It would be interesting to note the salary bill of clerks and ministers. It appears that about Rs. 16 a mouth is the rate for each clerk, and Rs. 100 a mouth is fixed for the highest officer of a State yielding Rs. 1.00,000. Incidentally we get an idea of what is known as the Standard of Life and Comfort among the ancient Hindus.

There is another item to be noted in this schedule. This is about Learning and Education. Patronage of Education and Promotion of Learning by means of stipends, scholarships; rewards, honorariums etc. are compulsory items that cannot be neglected in the monthly State-Budgets. Men of letters are among the primary charges upon the income of the ruler. Hence there is a definite provision for them in thei unit’ of disbursement or the normal Budget of the one lakh standard.

[16]:

The soldiers have to pay for their own uniforms. But it appears that the State is to get these prepared and not to make the individuals responsible. The system seems to be that of granting liveries and uniforms from the State.in exchange for the price to be paid by the soldiets. They cannot purchase these things in the open market at their own will.

[17]:

iṣṭacchāya—The tent on the chariot should be foldable and portable if need be, so that it may be convenient to regulate it according to the rays of the sun.

[18]:

[19]:

[20]:

siṃhākṣi—Eyes like those of the lion, i.e., which turn towards the back and the sides at intervals.

[21]:

The ‘Miśra’ would thus be a non-descript, incapable of being classified or specified as belonging to a particular type.

[22]:

The relative proportions of limbs vary with the three classes.

[23]:

The height of the Mandra would thus be five cubits, that of the Mṛga could be five cubits. The length of the Mandra would be seven cubits, that of the Mṛga would be six cubits. The circumference of the belly of the Mandra would be nine cubits that of the Mṛga would be eight cubits.

[24]:

This is a special rule modifying that in the previous line. According to 1. 81 the length of the mandra ought to be seven cubits, i.e., one cubit less than that of Bhadra. But by this rule the lengths are equal. So Mandra is eight cubits long. Therefore Mṛga is to be seven cubits not six as in I.81.

The following measurements are to be noted in II.77-82.

[25]:

śubhalakṣaṇa—But these lakṣaṇa or marks have not been mentioned in the Treatise.

[26]:

In measuring horses people use a different standard from that used’ for elephants.

(a) Elephant measure:—

| 8 Yavas | ... ... | 1 Aṅgula. |

| 24 Aṅgulas | ... ... | 1 Kara. |

(b) Comparative statement of limbs:—

| Bhadra. | Mandra. | Mṛga. | |

| Height | 7 karas | 6 karas | 5 karas. |

| Length | 8 karas | 8 karas | 7 karas |

| Circumference of belly... | 10 karas | 9 karas | 8 karas |

[27]:

[28]:

The limbs of the horses are to have a fixed proportion with the face. 'Ordinary horse-measurements are:—

| Stature... | ... ... | 3 faces. |

| Length... | ... ... | 4⅓ faces |

| Circumference of udara | ... ... | 3 faces + 3 aṅgulas. |

[29]:

śapha—heel or hoof.

manibandha—from heel to ankle.

caturhastāṅgulā—aṅgulas of four hands, i.e, 20 aṅgulas.

kūrpara—elbow, here the joint which connects the thighs with the trunk.

pratyak—back or hind. The back leg is thus twenty-eight minus seven or 21 aṅgulas.

[30]:

sārdhapādahīnā—the face by ¼th and ½ of ¼th, i.e., 28—(¼+⅛) of 24 aṅgulas or about 28-7-3 or 18 aṅgulas.

[33]:

The following are the measurements given in II.96-144. The type taken is that whose face is 28 aṅgulas. i.e., the lowest species.

| (a) Heights. | |

| 1. Heel or Hoof | 3 aṅgulas, |

| 2. Ankle-joint | 4 aṅgulas, |

| 3. Fore leg | 20 aṅgulas, |

| 4. Knee | 3 aṅgulas, |

| 5. Fore thigh | 14 aṅgulas, |

| 6. Thigh to neck | 38 aṅgulas, |

| 7. Hind legs | 28 aṅgulas, |

| 8. Hind thighs | 21 aṅgulas, |

| 9. Neck | 18 aṅgulas, |

| (b) Lengths. | |

| 1. Neck | 60 aṅgulas. |

| 2. Body | 60 aṅgulas, |

| 3. From organ to end of vertebral column | 18 aṅgulas, |

| 4. Tail | 14 aṅgulas, |

| 5. Genital organ | 14 aṅgulas, |

| 9. Testicles | 7 aṅgulas, |

| 7. Ear | 4, or 5 aṅgulas, |

| 8. Mane or Hair of neck | 1 cubit |

| 9. Hair of tail | 1½ or 2 cubits. |

| 10. Eye | 3 or 4 aṅgulas. |

| (c) Circumferences. | |

| 1. Heel... | ... 15 aṅgulas. |

| 2. Ankle-joint... | ... 7½ aṅgulas. |

| 3. Fore leg... | ... 7½ aṅgulas. |

| 4. Fore thigh... | ... 11 aṅgulas. |

| 5. Hind thighs00... | ... 88 aṅgulas. |

| 6. Hock of the anklejoint... | ... 9 aṅgulas. |

| 7. Hind leg... | ... 7½ aṅgulas. |

| 8. Forepart of neck | ... 32 aṅgulas. |