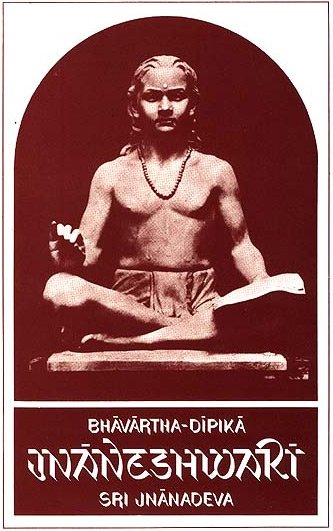

Jnaneshwari (Bhavartha Dipika)

by Ramchandra Keshav Bhagwat | 1954 | 284,137 words | ISBN-10: 8185208123 | ISBN-13: 9788185208121

The English translation of the Jnaneshwari (Dnyaneshwari), a Marathi commentary on the Bhagavad Gita from the 13th century written by Jnaneshwar (Sri Jnanadev). The Bhagavad Gita embodies the essence of the Vedic Religion and this commentary (also known as the Bhavartha Dipika) brings to light the idden significance and deeper meaning of the conver...

Bhagavad Gita (historical background and the context)

“Good (sometimes) cometh out of evil”—is an old adage. Good in the form of the supreme and most sublime philosophy contained in the teachings of “Bhagavad-Gita” came out of the evil in the form of the most bitter and deadly dispute between the two branches ‘Pandavas’ and the ‘Kauravas’ of the Lunar Dynasty, over sharing the sovereignty of ‘Bharata’. This is elaborated below.

There reigned at Hastinapur, about fifty miles from modem Delhi, in very ancient times about 2000 years before the Christian era—King Shantanu of the Bharata Dynasty. Once he happened to see Ganga, a Goddess and a holy river from the heavens, who had taken birth in human form on the earth, consequent on some curse inflicted on her. Shantanu and Ganga loved each other and their love eventually ripened into a marriage. Before they married, it was agreed between them that Ganga should have the sole claim over the progeny that might issue as the result of their marriage, and that, should King Shantanu behave in any way against that agreement, Ganga should forsake him forth-with. Ganga, after the marriage gave birth to seven sons, all of whom she consigned to the river. When she was about to make the eighth son meet the same fate. King Shantanu got overpowered with intense grief, and begged Ganga not to consign that child to the river, as he could not bear to see the loss of that child. Ganga did not, at the instance of God Indra, consign that child to the river, but forsook Shantanu according to the original agreement between them, since Shantanu’s request for the rescue of the child was taken as a breach of that agreement. This, in fact, took place in accordance with the predestined arrangement by which Ganga’s curse was to be mitigated, and she was to be restored to her original position in the Heavens.

That eighth son was named Devavriata and was brought up by King Shantanu with the greatest care. The young prince attracted the minds of the subjects in the kingdom by his excellent qualities. King Shantanu also loved Devavriata very dearly. In due course King Shantanu designated the young Prince as the heir-apparent; and entrusting him with the affairs of the state, he gave himself up to hunting and sports of that kind. While out hunting one day he happened to see a poor but gentle and charming Koli damsel (fisherwoman) named ‘Satyavati’. Deeply grieved and lonely as he had already felt at his separation from Ganga, Shantanu thought of taking Satyavati in marriage to mitigate his grief and loneliness, and he approached the girl’s father with the marriage proposal. Satyavati’s father showed himself in favour of the proposal, but stipulated that the son that might be born to Satyavati as the result of their marriage, should exclusively be the heir-apparent. King Shantanu could not agree to this condition on account of his strong affection for Devavrata, nor could his love for Satyavati get in any way diminished, the result being that his health began to get deteriorated. Devavriata came to know of this, and he did not like that he should himself be the cause of the suffering of his father. He, approached Satyavati’s father on his own, and after discussing the matter with him took the double vow that he would renounce all his claim to the throne, and he would also remain for ever a bachelor to preclude the possibility of any trouble ever arising in the future from his progeny. Satyavati’s father thereon agreed to Satyavati’s proposed marriage with Shantanu, which took place in due course. The Gods in the Heaven expressed their high appreciation of the sacrifice made by Devavriata, and bestowed on him the title of 'Bhishma,’ on account of his dreadful vow. He was known thus thereafter.

King Shantanu had two sons born of Satyavati, Chitrangada and Vichitravirya. The King died a little later and Bhishma installed the elder son Chitrangada on the throne. Chitrangada, however, died soon after in a battle, and Vichitravirya succeeded him. He married the two daughters of King Kashiraj, Ambika and Ambalika. Vichitravirya, however, soon died without any issue.

Satyavati was greatly distressed at these tragic happenings. Bhishma, her husband’s son from Ganga had already taken a vow to remain a bachelor permanently, while both her sons died without leaving any heir to the throne. There were left only the two childless young widows Ambika and Ambalika. Satyavati therefore laid before Bhishma alternate proposals viz. (al that he (Bhishma) should either himself occupy the throne and get himself married, or (b) in the alternative should practice ‘Niyoga’[1] on the widows of Vichitravirya and beget sons in order to prevent Bharata Dynasty from becoming extinct. Bhishma replied that he would never break his vow once taken. He, pointed out however that there was a mandate in the Scriptures that the Kshatriyas should beget sons through learned and austere Brahmins. This put Satyavati in mind of having got a son named Vyasa from Sage Parashar while in her virgin state at her father’s, and she told this to Bhishma; they both agreed to make use of Vyasa for the purpose. Satyavati recalled Vyasa to her mind and he stood before her. Satyavati related to him the purpose for which he was called, and he promised to act in the way suggested, provided the two ladies concerned would agree to have him with his ugly appearance and apparel, and also the foul smell emanating from his person. Satyavati consulted both her daughters-in-law and they with great reluctance agreed to the proposal. The elder one Ambika remained waiting for Vyasa, and when he actually came she saw his appearance with overgrown hair, reddish colour of his matted hair and red eyes etc., and she got frightened and closed her eyes and did not re-open them so long as Vyasa was with her. This resulted in Ambika giving birth to a blind son, who was later on known as Dhritarashtra. With a view to have a son, good and complete in all respects, in the royal dynasty Satyavati again called Vyasa and requested him to repeat his ‘Niyoga’ process on the younger daughter-in-law Ambalika and he agreed. When Ambalika saw him, she too got frightened and turned white. Vyasa perceived this and said that the son that would be born to her in such a state would be pale and this turned out to be true. This son was later on called ‘Pandu’ (colourless). Satyavati again requested her elder daughter-in-law to receive Vyasa once more, but she could not gather courage sufficient to face Vyasa once more, and she instead of going through the ordeal herself, deputed her maid-servant duly bedecked with ornaments etc. to receive Vyasa. The maid received Vyasa with very high regard, not minding his external appearance. Vyasa told her that she would be blessed with a son who would be highly talented and religious-minded and would also be a great devotee of God. The son born to this maid was named ‘Vidura’.

Bhishma brought up the three sons Dhritarashtra, Pandu, and Vidura with great care and made them well-versed in Vedic studies, archery, and the use of other arms and weapons. Pandu became specially expert in archery, blind Dhritarashtra became very strong bodily, while Vidura made a mark in intellectual feats. Bhishma installed Pandu on the throne, since it did not seem proper to him to install either Dhritarashtra or Vidura, the former being born blind and the latter being born of a maid servant. All the three sons were duly married. Dhritarashtra’s wife was named Gandhari; Pandu married two ladies named Pritha (Kunti) and the other Madri; while Vidura married the daughter of a king named Devaka. Pandu acquired vast riches through his valour and dedicated them all. with the consent of his elder brother Dhritarashtra, to Bhishma and Satyavati and his two mothers Ambika and Ambalika. He then went for hunting in the forests on the southern slopes of the Himalayas. While hunting one day. Pandu missed his aim and hit with his arrow a sage and his wife both of whom had assumed the forms of deer and were enjoying each other’s company. Before they died, however, the couple inflicted a curse on Pandu that he too would meet his death while in the enjoyment of his wife. Pandu felt extremely miserable at this happening and also at the curse, and began to observe devout austerity along with his wives in propitiation. As it was considered improper to die childless, Pandu broached the subject to his wife Kunti, and suggested that she should beget progeny by taking resort to ‘Niyoga.’ Kunti however observed that while at her father’s home in her virginity, she had secured a boon—a hymn from sage Durvasa, the recital of which gave her the power of attracting towards herself any God of her choice for begetting progeny. She added that she would avail herself of that power (instead of taking resort to “Niyoga”). This she did and she had three sons Dharma from Yamadharma, Bhima from Vayu and Arjuna from Indra respectively. The younger wife Madri followed the same course with the help of Kunti, the consent of Pandu, and she had two sons named Nakula and Sahadeva from the two Ashvinis. Thus Pandu secured in all five sons, who became known as Pandavas, while Dhritarashtra and his wife Gandhari got a progeny of 100 sons and one daughter, the sons being known as Kauravas.

No one can fight against fate and this proved too true in the case of Pandu. Even while in the full recollection of the dagger in the form of the curse hanging over his head, he, on one occasion, became extremely passion-stricken and in spite of strong protestation on the part of Madri, began having sexual intercourse with her, with the result that he suddenly collapsed and met his death. Madri entrusted her two sons to the fond care of Kunti, and as a true Sati immolated herself on the pyre of her husband Pandu. Kunti was then taken with the five sons to Hastinapura by the sages where Bhishma brought ‘them up along with the Kauravas. Bhishma got both the Kauravas and the Pandavs well-educated all-round. They were given special training in archery under Dronacharya. Dronacharya noticing the special aptitude of Bhima and Arjuna, specially initiated them in the mysteries and secrets of the art of archery. The superiority in the art of archery on the part of Bhima and Arjuna sowed the first seed of jealousy in the minds of the Kauravas against the Pandavas. The latter being virtuous became favourite with the elders and this led to increased bitterness of feelings against them on the part of Kauravas. The Kauravas entertained the fear that they would have to part with the entire kingdom, or at least half of it, in favour of the Pandavas, should they happen to make such a claim. Shakuni, the wily maternal-uncle of the Kauravas, fostered this fear in their minds, and he advised them to plan the total destruction of Pandavas. Attempts were accordingly made to bring about this result in various ways, such as by poisoning Bhima, setting fire to Pandavas’ dwelling, and also by drowning Bhima; but they all proved abortive. The Pandavas, on the other hand, acquired unlimited riches and this made the Kauravas feel greater jealously for the Pandavas. The Kauravas, as the last resort stooped to a device, common in those times, of tempting Dharmaraja—the eldest of the Pandavas—to a game of (loaded) dice, with the wicked motive of robbing him, through gambling, of all he possessed. Dharma fell an easy victim to the temptation, and the game started. Dharma getting intoxicated as the game advanced, went on laying stakes after stakes and losing heavily each time. Ultimately he lost everything leaving nothing that he could call his own and stake. The Kauravas most cunningly hinted that there was still left Draupadi—the common wife of the Pandavas who could be put as a stake. As ill luck would have it, in the heat of the moment, Dharma took up that hint and staked Draupadi, as practically the last stake. That stake too Dharma lost, and Draupadi became the property of the successful Kauravas. Taking advantage of that position, the Kauravas by way of wreaking bitter vengeance on Pandavas, went to the length of forcibly dragging Draupadi against her will to the court-hall, and insulting her there in the open court. Ultimately, the Kauravas stipulated that the Pandavas by way of expiation (of the sin) of losing all the stakes, should go into exile for a period of twelve years, and should further remain incognito for a period of one year. The Pandavas accordingly went into exile accompanied by Draupadi.

Ater suffering all sorts of possible hardships and with the termination of the period of thirteen years made up of exile and livings incognito, the Pandavas returned to Hastinapura, and, they claimed their half-share in the kingdom. The Kauravas who were from the beginning against recognizing any such claim, refused point-blank to give any share of the kingdom to the Pandavas. The eldest brother

Dharmaraja suggested a compromise with a view to preventing a quarrel, that the Pandavas should be given at least five towns and villages and they would rest content with that. Bhishma, Drona and Vidura had all tried their utmost to induce the Kauravas and their maternal uncle Shakuni (the arch instigator) to agree to the compromise but to no purpose. Even the blind Dhritarashtra wished in his heart of hearts, that justice should be done to the Pandavas, but he was helpless since his eldest son Duryodhana and his brothers refused to hear any such proposal. Even Lord Krishna (the eighth incarnation of God Vishnu in that era) went to mediate, but he too was not successful. All efforts at a compromise, having proved unavailing, Dharmaraja, the eldest of the Pandavas at last gave his consent to have resort to warfare on which the other Pandavas were so very keen and insistent. The Kauravas were prepared to face the ordeal of a war, and so both the parties prepared themselves. The Kauravas collected an army of eleven Akshauhinis, while the Pandavas collected an army of seven Akshauhinis—in all an army amounting to eighteen Akshauhinis[2] was collected on both sides.

Both the armies stood face to face on the battle field of Kurukshetra (near modem Delhi). Just as the fighting was about to begin, King Dhritarashtra expressed his longing to know the progress of the war as it took place. Being himself blind he could not view personally what actually took place on the battle-field. Sage Vyasa, therefore, deputed Samjaya—an expert, originally engaged for horse-testing, duly endowed with a divine vision, which enabled him to view clearly from any spot of safety he might select to watch from, to remain with Dhritarashtra, and narrate to him the progress of war as he could actually see it taking place.

During the war. Lord Krishna became the charioteer of Arjuna. Arjuna wished to see for himself, before the fighting actually commenced, who had collected on the battle-field on both the sides to take part in the fighting. He, therefore, asked Lord Krishna to take the chariot to a position midway between the two armies, which Lord Krishna did. As he saw all around, Arjuna perceived his grandfathers, uncles, brethren, friends, nephews, sons, preceptors and kinsmen-in fact all his kith and kin collected there to take part in the warfare, and a feeling of a dolour at what he saw, came over his mind. It was rather strange that Arjuna who had already known from the beginning who were getting together to take part in the warfare, and who was himself so eager for the destruction of the Kauravas whom he hated so much for all the injustice they had done to the Pandavas, should, at the very eleventh hour, feel nervous. Not only that, he began even to argue with Lord Krishna on the utter impropriety of conducting a warfare against his own kith and kin, and further to tender his own advice to him. Seeing this attitude on the part of Arjuna, Lord Krishna got puzzled and began to deprecate him for what he called his turbid mood. Arjuna had implicit faith in Lord Krishna and he surrendered himself completely to him and begged him to tell him for certain what was better for him (whether to fight or not to fight) in the circumstances in which he was placed, as he had become incapable of judging for himself on account of his dolorous state. Hearing Arjuna’s appeal Lord Krishna preached the right course for him to follow.

The advice then given by Lord Krishna to Arjuna, is contained in that portion of the great Epic Mahabharata composed by sage Vyasa which is called Bhagavadgita comprising 18 chapters with 700 stanzas. That discourse is in the form of a dialogue between Lord Krishna and Arjuna, at the conclusion of which Lord Krishna enquired of Arjuna if his ignorance-grounded misconception has been dispelled.

To this query Arjuna gave the following answer:

“Dispelled is mine dilusion; regained by me

through THY favour is the memory (consciousness

of my real nature) Oh Achyut! I stand here firm

and freed of doubt, and will do Thy bidding”.

Shri Jnanadev Maharaj composed in Marathi in a versified form an illuminating commentary on ‘Bhagavadgita’ which was originally in Sanskrit, and gave it the name ‘Bhavartha-dipika,’ the lamp illumining the import of the Teachings of the Gita, otherwise known as ‘Jnaneshwari.’

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

‘Niyoga’—A practice prevalent in ancient times, which permitted a childless widow to have intercourse with the brother or a near kinsman of her deceased husband to raise up issue to him. the son so born being called Kshetraja (kṣetraja)

[2]:

One Akshauhini (akṣauhiṇī) means an army of 218700, made up of elephants, chariots, horses and infantry.