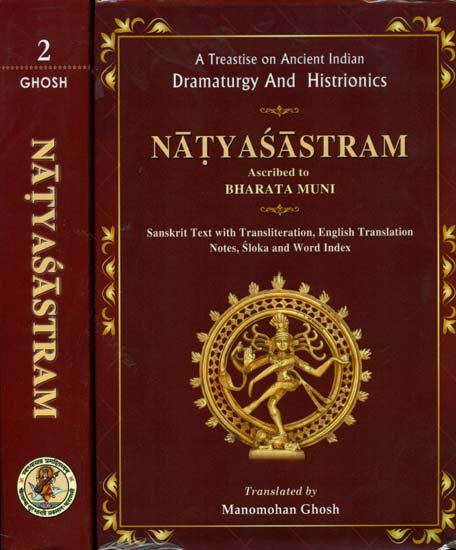

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 2 - The Ancient Indian Theory of Drama

1. The Meaning of Nāṭya

The word “Nāṭya” has often been translated as ‘drama’ and the plays of ancient India have indeed some points of similarity with those of the Greeks. But on a closer examination of the technique of their production as described in the Nāṭyaśāstra, the Hindu dramas represented by the available specimens, will appear to be considerably different. Unless this important fact is borne in mind any discussion on the subject is liable to create a wrong impression. As early as 1890 Sylvain Lévi (pp. 423-424) noticed that Indian Nāṭya differed from the Greek drama from which the Westerners derived their early conception of the art. Though it is not possible to agree with Lévi on all points about the various aspects of this difference and the causes which he attributed to them, no one can possibly have any serious objection against his finding that, “Le nāṭaka par se nature autant que par son nom se rapproache de la dance scenique; le drame est l’action même” (loc, cit), Lévi however did not for reasons stated above fully utilize in this connection the Nāṭyaśāstra which contains ample materials for clarifying his conclusion.

The essential nature of the (Nāṭya) derived from its etymology cannot by any means be called fanciful. For in the Harivaṃśa[1] (c. 200 A.C) we meet with an expression like nāṭakaṃ nanṛtuḥ (they danced a play) and the Karpūramañjarī[2] (c. 1000 A. C.) has an expression like saṭṭaṃ naccidavvaṃ (a Saṭṭaka is to be danced or acted).

The terms like rūpaka or rūpa (representation) and prekṣā (spectacle), all denoting dramatic works, also characterise the Hindu dramas and show their difference from the drama of the Greeks who laid emphasis on action and not on the spectacle. Of the sir parts of the tragedy, the most typical of the Greek dramatic productions, Aristotle puts emphasis on the fable or the plot and considers decoration to be unimportant. On tips point the philosopher says:

“Terror and pity may be raised by decoration—the mere spectacle; but they may also arise from the circumstance of the action itself, which is far preferable and shows a superior poet, For the fable should be so constructed that without the assistance of the sight its incidents may excite horror and commisseration in those who hear them only; * * * * But to produce this effect by means of the decoration discovers want of art in the poet; who must also be supplied with an expensive apparatus” (II.XIII).[3]

But in case of the Hindu dramas the decoration (i.e., the costumes and make-up) mostly plays an important part. Equally with five other elements such as gestures and postures (āṅgika), words (vācika), the representation of the Temperament (sattva), it gives the Nāṭya its characteristic form. But in the theatre of the Greeks, it was not the case. In the performance of the tragedies, for example, they did not care much for the spectcale, if the declamation was properly made. For Aristotle himself says that, “the power of tragedy is felt without representation and actors” (II.III).[4]

Another peculiarity of the Hindu dramas was their general dependence on dance (nṛtya), song (gīta), and instrumental music (vādya). Though the chorus of the Greek tragedy introduced in it some sort of dance and songs, the function of these elements seem to have been considerably different in the Hindu drama. The ancient Indian play was produced through words, gestures, postures, costumes, make-up, songs and dances of actors, and the instrumental music was played during the performance whenever necessary. But these different elements did not play an equal part in all the plays or different types of play. According as the emphasis was to be put on words, music, or dance, a play or its individual part partook of the nature of what the moderns would call ‘drama’, ‘opera’, ‘ballet’ or ‘dramatic spectacle’[5]. Due to this nature the Hindu dramas which connected themselves in many ways with song, dance and instrumental music, had a literary form which was to some extent different from that of the ancient Greeks. But it was not so much due to this literary form as to the technique of their production on the stage that the Hindu dramas received their special character.

After forming a general idea of this Nāṭya, from the various terms used to denote it, one should enquire what the ancient Indian theorists exactly meant by the term (Nāṭya) or what they regarded as being the essence of the dramatic art as opposed to the arts of poetry, fiction or painting. To satisfy, our curiosity on this point the Nāṭyaśāstra gives us the following passage which may pass for a definition of the Nāṭya.

“A mimicry of the exploits of gods, the Asuras, kings as well as of householders in this world, is called drama” (1.120).

This description seems to fall in a line with Cicero’s view that “drama is a copy of life, a mirror of custom, a reflection of truth”. In this statement Cicero evidently takes his cue from Aristotle who considered that the art in general consisted of imitation (mimesis). But this does not help us very much to ascertain the nature of drama as an example of ‘imitation’. For the Greek philosopher nowhere defines this very essentially important term. So when he declares that “epic poetry, tragedy, comedy, dythrambics as also for the most part the music of the flute and of the lyre all these are in the most general view of them imitations”[6], one can at best guess how drama imitates. There seems to be no such difficulty about understanding the view of the Hindu theorists. The Nāṭyaśāstra lays down very elaborate rules as to how the drama is to make mimicry of the exploits of men and their divine or semi-divine counterparts. It is due to rules of representation that the Hindu drama has been cal led by the later theorists ‘a poem to be seen’ (SD. 270-271). By this term epic or narrative poetry and fiction etc. are at once distinguished from drama which is preminently a spectacle including a mimicry of activities of mortals, gods or demigods. It may now be asked what exactly was meant by the word mimicry (anukaraṇa) used by the Indian theorists. Did this mean a perfect reproduction of the reality? For an answer to this question we are to look into the conventions of the Hindu drama.

2. The Dramatic Conventions

That the Hindu theorists turned their attention very early to the problem of dramatic representation and enquired about the exact place of realism or its absence in connection with the production of a play, is to be seen clearly from their very sensible division of the technical practice into “realistic” (lokadharamī, lit. popular) and “conventional” (nāṭyadharmi, lit. theatrical). By the realistic practice, the Nāṭyaśāstra (XIV. 62-76; XXIII. 187-188) means the reproduction of the natural behaviour of men and women on the stage as well as the cases of other natural presentation. But from the very elaborate treatment of the various conventions regarding the use of dance, songs, gestures and speeches etc. by different characters it is obvious that the tradition of the ancient Hindu theatre recognised very early the simple truth that the real art to deserve the name, is bound to allow to itself a certain degree of artificiality which receives its recognition through many conventions. One very patent example of this conventional practice on the stage, is speeches uttered ‘aside’ or as soliloquy. The advocates of extreme realism may find fault with these as unnatural; and the accusation cannot be denied, but on closer examination of circumstances connected with the construction of a play as well as its production on the stage, it will be found that if the spectators are to demand realism very rigidly then no theatrical performance of any value, may be possible. Neither the Hindus nor the Greeks ran after this kind of absurdity. Critics of ancient Indian dramas will do well to remember this and to take care to understand the scope and necessity of various conventions relating to the production, so that they may better appreciate the art of great play-wrights like Bhāsa, Kālidāsa, Śūdraka and Viśākhadatta.

3. Time and place in Drama

Hindu playwrights, unlike the majority of Greek tragedians, did never make any attempt to restrict the fictional action to a length of time roughly similar to that taken up by the production of a drama on the stage. In developing plots they had not much restriction on the length of time, provided that individual Acts were to include incidents that could take place in course of a single day, and nothing could be put in there to interrupt the routine duties such as saying prayers or taking meals (XX 23), and the lapse of time between two Acts, which might be a month or a year (but never more than a year)[7] was to be indicated by an Introductory Scene (praveśaka) preceding the last one (XX. 27-28).

Similarly there was almost no restriction about the locality to which individual Actors, and gods in their human roles were to be assigned, except that the human characters were always to be placed in India i.e. Bhāratavarṣa (XX. 97).

4. The Unity of Impression

In spite of having no rules restricting the time and place relating to different incidents included in the plot of a drama, the playwright had to be careful about the unity of impression which it was calculated to produce. For this purpose the Nāṭyaśāstra seems to have the following devices:

The Germ (bīja) of the play as well as its Prominent Point (bindu) was always to relate to every Act of the play and the Hero was sometimes to appear in every Act or to be mentioned there (XX. 15, 30).

An Act was not to present too many incidents (XX.24), and such subsidiary events as might affect the unity of impression on their being directly presented, were merely to be reported in an Introductory Scene. Besides this, short Explanatory Scenes were sometimes put in before an Act to clarify the events occuring in it (XXI). 106-111. All these, not only helped the play to produce an unity of impression but also imparted to its plot a rapidity of movement which is essential for any kind of successful dramatic presentation.

5. Criticism of Drama

Indians from very early times considered plays to be essentially ‘spectacle’ (prekṣā) or ‘things’ to be visualised; hence persons attending the performance of a play were always referred to (XXVII. 48-57) as ‘spectators’ or ‘observers’ (prekṣaka)[8] and never as audience (śrotṛ), although there was always the speech element in it, which was a tiling to be heard. This disposes of the question of judging the value of a drama except in connection with its production on the stage This importance of the representational aspect of a play has possibly behind it an historical reason. Though in historical times we find written dramas produced on the stage, this was probably not the case in very early times, and the dialogues which contribute an important part of the drama were often improvised on the stage by the actors[9], and this practice seems to have continued in certain classes of folk-plays till the late medieval times[10]. Hence the drama naturally continued to bo looked upon by Indians as spectacles even after great playwright creators like Bhāsa, Kālidāsa, Śūdraka, and Bhavabhūti had written their dramas which in spite of their traditional form were literary master-pieces.

Now, dramas being essentially things to be visualised, their judgement should properly rest with the peoplo called upon to witness them. This was not only the ancient Hindu view, even the modern producers, in spite of their enlisting the service of professional (dramatic) critics, depend actually on the opinion of the common people who attend their performance.

The judgement of the drama which is to depend on spectators has been clearly explained in the theory of the Success discussed in the Nāṭyaśāstra (XXVII). In this connection one must remember the medley of persons who usually assemble to witness a dramatic performance and what varying taste and inclinations they might possess. For, this may give us some guidance as to what value should bo put on their judgement which appear to have no chance of unity. In laying down the characteristics of a drama the Nāṭyaśāstra has the following: “This (the Nāṭya) teaches duty to those bent on doing their duty, love to those who are eager for its fulfilment, and it chastises those who are ill-bread or unruly, promotes self-restraint in those who are disciplined, gives courage to cowards, energy to heroic persons, enlightens men of poor intellect and gives wisdom to the learned. This gives diversion to kings, firmness [of mind] to persons afflicted with sorrow, and [hints of acquiring] wealth to those who are for earning it, and it brings composure to persons agitated in mind. The drama as I have devised, is a mimicry of actions and conducts of people, which is rich in various emotions and which depicts different situations. This will relate to actions of men good, bad and indifferent, and will give courage, amusement and happiness as well as counsel to them all” (I.108-112).

It may be objected against the foregoing passage that no one play can possibly please all the different types of people. But Jo take this view of a dramatic performance, is to deny its principal character as asocial amusement. For, the love of spectacle is inherent in all normal people and this being so, every one will enjoy a play whatever be its theme, unless it is to contain anything which is anti-social in character. The remarks of the author of the Nāṭyaśāstra quoted above on the varied profits the spectators will reap from witnessing a performance, merely shows in what diverse ways different types of plays have their special appeal to the multitudinous spectators. And his very detailed treatment of this point, is for the sake of suggesting what various aspects a drama or its performance may have for the spectators. This manysidedness of an ideal drama has been very aptly summed up by Kālidāsa who says, “The drama, is to provide satisfaction in one [place] to people who may differ a great deal as regards their tastes” (Mālavi. I.4). It is by way of exemplifying the tastes of such persons of different category that the Nāṭyaśāstra says:

“Young people are pleased to see [the presentation of] love, the learned a reference to some [religious or philosophical] doctrine, the seekers after money topics of wealth, and the passionless in topics of liberation.

Heroic persons are always pleased in the Odious and the Terrible Sentiments, personal combats and battles, and the old people in Purāṇic legends, and tales of virtue. And common women, children and uncultured persons are always delighted with the Comic Sentiment and remarkable Costumes and Make-up” (XXV.59-61).

These varying tastes of individual spectators were taken into consideration by the author of the Nāṭyaśāstra when he formulated his theory of the Success. The Success in dramatic performance was in his opinion of two kinds, divine (daivikī) and human (mānuṣī) (XXVII.2). Of these two, the divine Success seems to be related to the deeper aspects of a play and came from spectators of a superior order i.e. persons possessed of culture and education (XXVII.16-17), and the human Success related to its superficial aspects and came from the average spectators who were ordinary human beings. It is from these, latter, who are liable to give expression to their enjoyment or disapproval in the clearest and the most energetic manner, that tumultuous applause and similar other acts proceeded (XXVII.3, 8-18, 13-14), while the spectators of the superior order gave [their appreciation of the deeper and the more subtle aspects of a play (XXVII, 5, 6,12, 16-17). During the medieval times the approval of the spectators of the latter kind came to be considered appreciation par excellence and pre-occupied the experts or learned critics. They analysed its process in every detail with the greatest possible care in their zealous adherence of Bharata’s theory of Sentiment (rasa) built upon what may be called a psychological basis.

But in spite of this later development of this aspect of dramatic criticism it never became the preserve of specalists or scholars. Critics never forgot that the drama was basically a social amusement and as such depended a great deal for its success on the average spectator. Even the Nāṭyaśāstra has more than once very clearly said that the ultimate court of appeal concerning the dramatic practice was the people (XX.125-126). Hence a fixed set of rules, be it of the Nāṭyaveda or the Nāṭyaśāstra was never considered enough for regulating the criticism of a performance. This seems to be the reason why special Assessors appointed to judge the different kinds of action occurring in a play (XXVI.68-69), decided in co-operation with the select spectators, who among the contestants deserved to be rewarded.

6. The Four Aspects of Drama.

Though the Hindu plays are usually referred to as ‘drama’ all the ten varieties of play (rūpa) described in the Nāṭyaśāstra are not strictly speaking dramas in the modern sense. Due to the peculiar technique of their construction and production they would partially at least partake of the nature of pure drama, opera, ballet or merely dramatic spectacle. To understand this technique one must have knowledge of the Styles (vṛtti) of dramatic production described in the Nāṭyaśāstra (XXII). These being four in number are as follows: the Verbal (bhāratī), the Grand (sāttvatī), the Energetic (ārabhatī) (Ārabhaṭī?) and the Graceful (kaiśikī). The theatrical presentation which is characterised by a preponderating use of speech (in Skt.) and in which male characters are exclusively to be employed, is said to be in the Verbal Style (XXII.25ff.). This is applicable mainly in the evocation of the Pathetic and the Mervellous Sentiments. The presentation which depends for its effect on various gestures and speeches, display of strength as well as acts showing the rise of the spirits, is considered to be in the Grand Style (XXII.38ff). This is applicable to the Heroic, the Marvellous and the Furious Sentiments. The Style which includes the presentation of a bold person speaking many words, practising deception, falsehood and bragging and of falling down, jumping, crossing over, doing deeds of magic and conjuration etc, is called the Energetic one. This is applicable to the Terrible, the Odious and the Furious Sentiments (XXII. 55ff). The presentation which is specially interesting on account of charming costumes worn mostly by female characters and in which many kinds of dancing and singing are included, and the themes acted relate to the practice of love and its enjoyment, is said to constitute the Graceful Style (XXII.47ff). It is proper to the Erotic and the Comic Sentiments.

From a careful examination of the foregoing descriptions one will see that the Styles, excepting the Graceful, are not mutually quite exclusive in their application. On analysing the description of different types of play given in the Nāṭyaśāstra it will be found that the Nāṭaka, the Prakaraṇa. the Samavakāra and the Īhāmṛga may include all the Styles in their presentation, while the Ḍima, the Vyāyoga, the Prahasana, the Utsṛṣṭikāṅka, the Bhāṇa and the Vīthī, only some of those (XX.88, 96). Hence one may call into question the soundness of the fourfold theoretical division of the Styles of presentation. But logically defective though this division may appear, it helps one greatly to understand the prevailing character of the performance of a play as it adopts one or more of the Styles, and gives prominence to one or the other. It is a variation of emphasis on these, which is responsible for giving a play the character of a drama (including a dramatic spectacle), an opera or a ballet. Considered from this standpoint, dramas or dramatic spectacles like the Nāṭaka, the Prakaraṇa, the Samavakāra and the Īhāmṛga may, in their individual Acts, betray the characteristics of an opera or a ballet. The Prahasana, an one Act drama to be presented with attractive costumes and dance, may however to some extent, partake of the nature of a ballet. The Ḍima, the Vīthī, the Bhāṇa, the Vyāyoga and the Utsṛṣṭikāṅka are simple dramas devoid of dance and colourful costumes.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

Viṣṇuparvan, Ch. 93.81.28.

[2]:

Ed. M. Ghosh, p. 80.

[3]:

Poetics (Everymans Library), p. 27.

[4]:

ibid. p. 17.

[5]:

H.H. Wilson, On the Dramatic System of the Hindus, Calcutta, 1827, pp. 16.20.

[6]:

Poetics, p. 5.

[7]:

Bhavabhūti however violates the rule in his Uttara, in letting many years pass between Acts I and II.

[8]:

Prekṣā occurring in NŚ. III.99. scorns to bo the same as ‘pekkha’ mentioned in Pall Brahamajālasutta See Lévi. II. p. 54.

[9]:

Winternitz, Vol. I. pp, 101-102.

[10]:

The Kṛṣṇakirtana, a collection of Middle Bengali songs on Kṛṣṇa and Rādhā’s love-affairs, seems to have been the musical framework of a drama. We saw in our early boyhood that extemporised dialogues wore a special feature of the old type Bengali Yātrās. These have totally disappeared now under the influence of modern theatre which depend on thoroughly written plays.