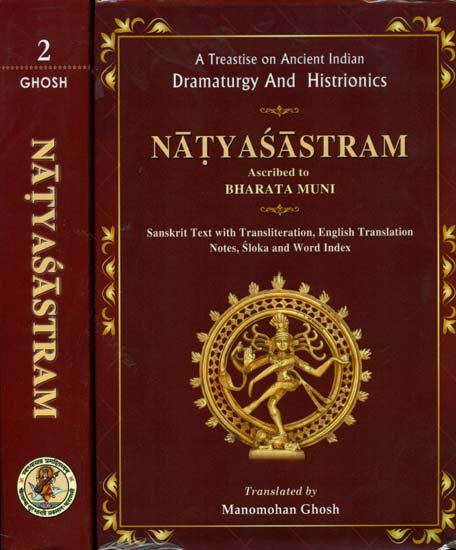

Natyashastra (English)

by Bharata-muni | 1951 | 240,273 words | ISBN-13: 9789385005831

The English translation of the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit work on drama, performing arts, theater, dance, music and various other topics. The word natyashastra also refers to a global category of literature encompassing this ancient Indian tradition of dramatic performance. The authorship of this work dates back to as far as at least the 1st millenn...

Part 3 - Literary Structure of the Drama

1. Ten Types of Play

The Nāṭaka. To understand the literary structure of the Hindu drama, it will be convenient to take up first of all the Nāṭaka which is the most important of the ten kinds of play described in the Nāṭyaśāstra[1].

(a) Subject-matter and division into Acts.

The Nāṭaka is a play having for its subject-matter a well-known story and for its Hero a celebrated person of exalted nature. It describes the character of a person descending from a royal seer, the divine protection for him, and his many superhuman powers and exploits, such as success in different undertakings and amorous pastimes; and this play should have an appropriate number of Acts (XX.10-12).

As the exploits of the Hero of the Nāṭaka have been restricted to his success in different undertakings including love-matters, it is a sort of ‘comedy’, and as such it can never permit the representation of the Hero’s defeat, flight or capture by the enemy or a treaty with him under compulsion. Such a representation would negative the subject of the play which is the triumph or the prosperity of the Hero. But all these except his (the Hero’s) death, could be reported in an Introductory Scone which may come before an Act. The presentation of the Hero’s death was for obvious reasons impossible in a comedy.

The first thing that attracts the attention of reader on opening a Nāṭaka, is its Prologue (sthāpanā or prastavanā). But according to the Nāṭyaśāstra this was a part of the Preliminaries (pūrvaraṅga) and was outside the scope of the play proper (V.171). That famous playwrights like Bhāsa, Kālidāsa and others wrote it themselves and made it the formal beginning of their dramas, seems to show that they made in this matter an innovation which as great creative geniuses they were fully entitled to.

But unlike the Greek plays the Hindu Nāṭakas are divided into Acts the number of which must not be less than five or more than ten (XX.57). These Acts, however, are not a set of clearly divided scenes as they usually are in modern western compositions of this category. An Act of the Hindu drama consists of a series of more or less loosely connected scenes[2] which due to its peculiar technique could not be separated from one another. It has three important characteristics.

(i) Only the royal Hero, his queen, minister, and similar other important personages are to be made prominent in it and not any minor character (XX.18). This rule seems to be meant for securing the unity of impression which has been referred to before.

(ii) It is to include only those incidents which could take place in course of a single day (XX.23). If it so happens that all the incidents occurring within a single day cannot be accommodated in an Act these surplus events are to be reported in a clearly separated part of it, called the Introductory Scene (praveśaka) where minor characters only can take part (XX.27, 30), The same should be the method of reporting events that are to be shown as having occurred in the interval between two Acts (XX.31). Evidently those latter should be of secondary importance for the action of play, But according to the Nāṭyaśāstra these; should not cover more than a year (XX.28). This allowance of a rather long period of time for less important events occurring between two Acts of a Nāṭaka was the means by which the Hindu playwrights imparted speed to the action of the play and compressed the entire plot distributed through many events over days, months and years within its narrow frame-work suitable for representation within a few hours.

(iii) An Act should not include the representation of events relating to feats of excessive anger, favour and gift, pronouncing a course, running away, marriage, a miracle, a battle, loss of kingdom, death and the siege of a city and the like (XX.20, 21). The purpose of this prohibition was probably that, when elaborately presented in an Act, these might divert much of the spectator’s interest from the line of the principal Sentiment which the play was to evoke and might therefore interfere width the unity of impression which it was to make.

(b) Explanatory Devices

(i) The Introductory Scene. It has been shown before how the Hindu playwrights divided the entire action of the Nāṭaka into two sets of events of which the one was more important than the other, and how they represented in its Acts the important set, whereas the less important ones were reported, whenever necessary, in an Introductory Scene giving one the idea of the time that intervened between any two Acts. This Scene is one of the five Explanatory Devices (arthopakṣepaka) which were adopted by the playwright for clarifying the obscurities that were liable to occur due to his extreme condensation of the subject-matter.

The other Explanatory Devices are as follows: The Intimating Speech (cūlikā), the Supporting Scene (viṣkambhaka) the Transitional Scene (aṅkāvatāra) and the Anticipatory Scene (aṅkāmukha).

(ii) The Intimating Speech. When some points [in the play] are explained by a superior, middling or inferior character from behind the curtain, it is called the Intimating Speech (XXL.108).

(iii) The Supporting Scene, The Supporting Scene relates to the Opening Juncture only of the Nāṭaka. It is meant for describing some incident or occurrence that is to come immediately after (XXI.106-107).

(iv) The Transitional Scene. When a scene which occurs between two Acts or is a continuation of an Act and is included in it, relates to the purpose of the Germ of the play, it is called the Transitional Scene (XXI.112).

(v) The Anticipatory Scene, When the detached beginning of an Act is summarised by a male or a female character, it is called the Anticipatory Scene (XXI.112).

(c) The Plot and its Development

The Plot or the subject-matter (vastu) of a Nāṭaka may be twofold: “The principal” (ādhikārika) and the “incidental" (prāsaṅgika), The meaning of the principal Plot is obvious from its name, and an incidental Plot is that in which the characters acting in their own interest incidentally further the purpose of the Hero of the principal Plot (XXI.2-5).

The exertion of the Hero for the result to be attained, is to be represented through the following five stages (XXI. 8): Beginning (ārmbha), Effort (prayatna), Possibility of Attainment (prāpti-sambhava), Certainty of Attainment (niyatapti) and Attainment of the Result (phalaprāpti). These five stages of the Plot have five corresponding Elements of the Plot (XXI.20-21) such as the Germ (bīja), the Prominent Point (bindu) the Episode (pātakā), the Episodical Incident (prakarī) and the Dénouement (kārya). Besides these aspects of the action and the Plot of the Nāṭaka, the elaboration of the latter has been viewed as depending on its division into the following five Junctions which are as follows: the Opening (mukha), the Progression (pratimukha), the Development (garbha), the Pause (vimarśa) and the Conclusion (nirahaṇa).

And these have been further subdivided and described to give detailed hints as to how the playwright was to produce a manageable play including events supposed to occur during a long period of time.

Kālidāsa’s Śakuntalā and Bhāsa’s Svapna-vāsavadattā are well-known examples of the Nāṭaka.

The Prakaraṇa. The second species of Hindu play, is the Prakaraṇa which resembles the Nāṭaka in all respects except that “it takes a rather less elevated range”. Its Plot is to be original and drawn from real life and the most appropriate theme is love. The Hero may be a Brahmin, merchant, minister, priest, an officer of the king or a leader of the army (XX.49-51). The female characters include a courtezan or a depraved woman of good family (XX.53)[3]. But the courtezan should not meet the Hero when he is in the company of a lady or gentleman of high family, and if the courtezans and respectable ladies must meet on any account they are to keep their language and manners undistorted (XX.55-56). From these and other features, the Prakaraṇa has been called a bourgeois comedy or comedy of manners of a rank below royalty.

Śūdrakas Mṛcchakaṭika and Bhavabhūti’s Mālatīmādhava are well-known examples of the Prakaraṇa.

The Samavakāra. The Samavakāra is the dramatic representation of some mythological story which relates to gods and some well-known Asura, who must be its Hero. It should consist of three Acts which are to take for their performance eighteen Nāḍikās (seven hours and twelve minutes).[4] Of these the first Act is to take twelve and the second four and the third two Nāḍikās only. The subject-matter of the Samuvakāra should present deception, excitement or love, and the number of characters allowed in it are twelve. And besides this, metres used in it should be of the complex kind (XX.63-76).

No old specimen of this type of drama has reached us. From the description given in the Nāṭyaśāstra it seems that the Samavakāra was not a fully developed drama, but only a dramatic spectacle on the sasis (basis?) of a mythological story. It naturally became extinct with the development and production of full fledged literary dramas such as those of Bhāsa and Kālidāsa.

Īhāmṛga. The Īhāmṛga is a play of four Acts in which divine males are implicated in a fight over divine females. It should be a play with well-ordered construction in which the Plot of love is to be based on causing discord among females, carrying them off and oppressing [the enemies], and when persons intent on killing are on the point of starting a fight, the impending battle should be avoided by some artifice (XX.78-82).

No old specimen of this type of play has been found. From the description given in the Nāṭyaśāstra it seems that the Īhāmṛga was a play of intrigue, in which gods and goodesses only took part.

The Ḍima. The Ḍima is a play with a well-constructed Plot and its Hero should be well-known and of the exalted type. It is to contain all the Sentiments except the Comic and the Erotic, and should consist of four Acts only. Incidents depicted in it are mostly earthquake, fall of meteors, eclipses, battle, personal combat, challenge and angry conflict. It should abound in deceit, jugglery and energetic activity of many kinds. The sixteen characters which it must contain are to include different types such as gods, Nāgas, Rākṣasas Yakṣas and Piśācas (XX.84-88).

No old or new example of this type of play has reached us. It seems that like the Samavakāra this was a dramatic epectacle rather than a full fledged drama. With the advent of literary plays of a more developed kind, it has naturally become extinct.

Vyāyoga. The Vyāyoga is a play with a well-known Hero and a small number of female characters. The events related in it arc to be of one day’s duration. It is to have one Act only and to include battle, personal combat, challenge and angry conflict (XX.90-92).

Bhāsa’s Madhyama-vyāyoga is a solitary old specimen of this type of play.

Utsṛṣṭikāṅka, The Utsṛṣṭikāṅka or Aṅka is an one-act play with a well-known plot, and it includes only human characters. It should abound in the Pathetic Sentiment and is to treat of women’s lamentations and despondent utterances when battle and violent fighting have ceased, and its Plot should relate to the downfall of one of the contending characters (XX.94-100).

Bhāsa’s Urubhaṅga seems to be its solitary specimen. This type of play may be regarded as a kind of one-act tragedy.

The Prahasana. The Prahasana is a farce or a play in which the Comic Sentiment predominates, dud it too is to consist of one Act only.

The object of laughter is furnished in this, mainly by the improper conduct of various sectarian teachers as well as courtezans and rogues (XX.102-106).

The Mattavilāsa and the Bhagavaḍajjukīya are fairly old specimens of this type of play.

The Bhāṇa. The Bhāṇa is an one Act play with a single character who speaks after repeating answers to his questions supposed to be given by a person who remains invisible, throughout. This play in monologue relates to one’s own or another’s adventure. It should always include many movements which arc to be acted by a rogue or a Parasite (XX.108-110). The Bhāṇas included in the collection published under the title Caturbhāṇī seem to be old specimens of this type of play.

The Vīthī, The Vīthī should be acted by one or two persons. It may contain any of the three kinds of characters superior, middling and inferior (XX.112-113). It seems to be a kind of a very short one Act play. But one cannot be sure about this; for no specimen of this type of play has come down to us.

2. Diction of a Play

(a) The Use of Metre.

One of the first things to receive the attention of the Hindu writers on dramaturgy was the importance of verse in the dramatic dialogue. They discouraged long and frequent prose passages on the ground that these might prove tiresome to spectators (XX.34). After giving a permanent place to verse in drama the Hindu theorists utilised their detailed knowledge of the structure of metres which varied in cæsura as well as the number and sequence of syllables or moras in a pāda (XV.38ff, XIV.1-86), for heightening the effect of the words used, by putting them in a appropriate metres. In this respect they framed definite r?les as to the suitability of particular metres to different Sentiments. For example, the description of any act of boldness in connexion with the Heroic and the Furious Sentiments is to be given in the Āryā metre, and compositions meant to express the Erotic Sentiment should be in gentle metres such as Mālinī and Mandākrāntā, and the metres of the Śakkarī and the Atidhṛti types were considered suitable for the Pathetic Sentiment (XVII.110-112). In this regard the Hindu theorists, and for that matter, the Hindu playwrights anticipated the great Shakespeare who in his immortal plays made “all sorts of experiments in metre”.

(b) Euphony.

After considering the use of metres the author of the Nāṭyaśāstra pays attention to euphony and says, “The uneven and even metres which have been described before should be used in composition with agreeable and soft sounds according to the meaning intended.

The playwright should make efforts to use in his composition sweet and agreeable words which can be recited by women.

A play abounding in agreeable sound and sense, and containing no obscure or difficult words, intelligible to the country people, having a good construction, fit to be interpreted with dances, developing Sentiments becomes fit for representation to spectators” (XVII.119-122).

(c) Suggestive or Significant names.

Another important aspect of the diction was the suggestive or significant names for different characters in a play. It has been said of Gustave Flaubert that he took quite a long time to find a name for the prospective hero and heroine of his novels, and this may appear to be fastidious enough. But on discovering that the Hindu dramatic theorists centuries ago laid down rules about naming the created characters (XIX.30-36), we come to appreciate and admire the genius of the great French writer.

(d) Variety of languages or dialects.

The use of Sanskrit along with different dialects of Prakrit (XVIII.36-61) must be ascribed to circumstances in the midst of which the Hindu drama grew up. The dramas reflect the linguistic condition of the society in which the early writers of plays lived. As the speech is one of the essential features of a person’s character and social standing, it may profitably be retained unaltered from the normal. Even in a modern drama dialacts are very often used though with a very limited purpose.

Footnotes and references:

[1]:

NŚ. ignores the Uparūpakas. For these see SD. NL. and BhP. etc.

[2]:

See note 2 in IV. below.

[3]:

Wilson who did not see the N.Ś., said, “We may however observe to the honour of the Hindu drama that the parakīyā or she who is the wife of another is ne??r to be mate the object of dramatic intrigue, a prohibition which could sadly have cooled the imagination and curbed the wit of Dryden and Congreve (Select S pecimens of Hindu Theatre, Vol. I. p. xiv.).

[4]:

See H.H. Wilson, On the Dramatic System of the Hindus, Calcutta, 1827, p. 16.